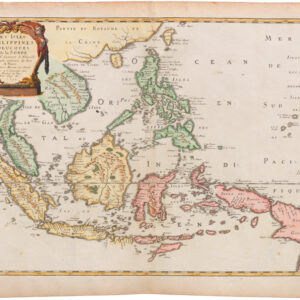

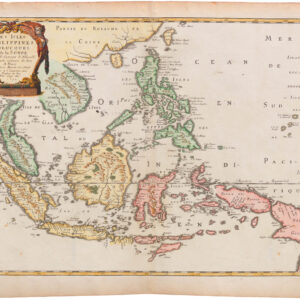

Blaeu’s iconic map of the Spice Islands/Moluccas.

Moluccae Insulae Celeberrimae

$850

1 in stock

Description

Listen to a short introduction to this map:

This is a well preserved and spectacularly colored copy of Willem Blaeu’s seminal map of the Spice Islands. Initially mapped by the Dutchman Peter Plancius in 1593, cartographic information on this region was virtually kept as a state secret by the Dutch government, which was at the time making a fortune on Holland’s dominant position in the international spice trade.

After twenty years of secrecy, the Plancius map was finally published under license by Nicholas Visscher in 1617 and was quickly adapted by other Dutch cartographers, especially the Hondius family. When Jodocus Hondius II — the original engraver of this map — died, Blaeu acquired the plates from the estate and modified them to appropriate the map as his own. The first edition of the Blaeu version was published in Willem Blaeu’s Atlantis appendix from 1630 onwards. In 1640, the map won a more prominent place in Willem and Joan Blaeu’s joint Theatrum Orbis Terrarum sive Atlas Novus. Our copy of this beautiful map comes from the German version of this publication. The atlas would form the basis for Joan Blaeu’s more famous Atlas Maior (1662-70), which is considered one of the last masterpieces of the golden age of Dutch cartography (c. 1570-1670).

Map elements

The map depicts the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas), which are an island group in the great Indonesian archipelago. From the 16th century they were known in Europe as the Spice Islands, since this is where especially the Dutch and Portuguese traders derived the precious commodities of cloves, nutmeg, and mace. The map is oriented with West at the top. At the bottom of the map we find Gilolo Island (Halmahera), the largest north Moluccan island and an important source of spices. In addition to coastlines, forests, and plantations, the map depicts a number of European fortifications.

Being of specific interest to traders, Blaeu has essentially compiled a nautical chart with a complex network of sight or rose lines. These link up in two 16-point compass-roses, as well as several secondary nexuses. Yet the map is not only accurate and functional, it is also extremely decorative and executed to the highest aesthetic standards. As such, it is a perfect example of why Willem Blaeu achieved the high recognition he did during his lifetime. In addition to the map itself, which is expertly engraved in a beautiful figurative style, we find a voluptuous title cartouche, an elaborate inset map of the island of Bachian (Batjan), a figurative scene in the lower right corner, and an abundance of ships in the waters around the islands. And of course, no Dutch map from this era is complete without a sea monster or two.

Both the figurative scene and the composition of the ships convey a somewhat cosmopolitan atmosphere in which the local and the European are juxtaposed. In the figurative scene in the lower right corner, we see this in the fact that the couple depicted here are indigenous Moluccans dressed in European garb. In regard to the ships, Blaeu has opted to depict a combination of European merchant vessels and local trading ships, some of which are rather substantial. It is as if he wishes to instill a sense of these distant commercial hubs in his viewers. That such interactions were not always peaceful is seen in the pair of ships above Ternate, which are clearly firing their cannons upon each other.

European fortifications in the north Moluccas

The focus on the northern islands around Ternate is part of the historical background for the Dutch presence here. During the era of Portuguese influence in the region, the Sultanate of Ternate felt increasingly marginalized and so when the Dutch arrived in the region around the turn of the century, the Sultan allied himself with them and expelled the Portuguese. The alliance cemented the north Moluccas as the primary Dutch base. The insert of Bachian, with it wonderful natural harbor, was included due to its status as an important regional centre of commerce and administration.

The islands of the map are also quite detailed and provide a glimpse into a very specific period of their history. On the large island of Ternate, we see no less than three fortified settlements: one on the east (bottom) coast, the second at the island’s southwestern tip, and the third along a cove at its northwestern end. These three settlements represent the Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch presence on this one island, and reveal just how intense competition for the Moluccan trade was. While the Dutch may have expelled the Portuguese in 1605, the Spanish only abandoned their fortification in 1662, and thus not until decades after this map was compiled.

The combination of its beauty and historical significance has made this map a sought-after collector’s item, not to mention the logo of the Miami Map Fair!

Context is everything

Since the 16th century, European traders have sailed on the Moluccas to trade spices. The Moluccas are a large Indonesian archipelago, located between Timor and New Guinea, and especially the northern islands of Ternate, Tidore, and Halmahera were very rich in cloves. Cloves were perhaps the most desired spice of them all among European consumers, and from 1529 they were exclusively traded from Lisbon and Antwerp. Other spices from this region included nutmeg and mace.

The first European to settle on Ternate was the Portuguese Francisco Serrão in 1512. Soon after, a Portuguese fort was established and by the time Magellan was completing his circumnavigation of the globe in 1520-21, the Moluccas were a natural stopping point on his route. In fact, Magellan’s flagship, the Trinidad, attempted to return home laden with cloves several times without luck, and would ultimately succumb to disrepair and violent weather off Ternate.

In his Itinerario, Jan Huygens van Linschoten — a Dutch seafarer in service of the Portuguese viceroy of Goa — had given an accurate description of the local situation and of the Portuguese settlements there. Linschoten spilled many Portuguese secrets to his fellow Dutchmen and ultimately assisted them in breaking Portuguese trade monopoly in the Indian Ocean.

The first Dutch contact with Ternate was made in 1599. By 1605, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) expelled the Portuguese from Tidore and soon after negotiated an exclusive contract with the Sultan of Ternate in exchange for military support. Within a few years, the VOC had constructed a fort on the island named Fort Oranje, and this became their first official headquarters, prior to moving their entire operation to the Dutch gubernatorial capital on Java in 1619.

Cartographer(s):

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638) was one of the most important Dutch geographers and mapmakers of the 17th century. He was born the son of a herring merchant but traded fishmongering for studies in mathematics and astronomy. Blaeu’s first important breakthrough was winning an apprenticeship with the famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. Working at Brahe’s Uranienborg observatory on the island of Hven, Blaeu learned various disciplines and technical skills. These included mathematics, astronomy, instrument-making, and more esoteric disciplines such as alchemy. Returning to his native Holland, Blaeu established a publishing business in Amsterdam. He sold instruments and globes, printed maps, and his own editions of some of the great philosophical works of contemporary intellectuals like Descartes and Hugo Grotius. Achieving notoriety as a cartographic pioneer, Blaeu was appointed Chief Hydrographer to the powerful Dutch East India Company, a position he held until he died in 1638.

When Willem died, his sons Cornelis (1610-1648) and Joan (1596-1673) took over the business. Joan had originally trained as a lawyer but never took up the practice, preferring to work on maps with his father. After Willem’s death, Joan continued publishing his father’s and his own maps. He also assumed his father’s position as a hydrographer for the Dutch East India Company. Towards the end of his life, Joan would dramatically expand his father’s Atlas Novus (1635), turning it into his own masterpiece, the Atlas Maior (1662-72).

When Willem died, his two sons Cornelis (1610-1648) and Joan (1596-1673) took over the business. Joan had originally trained as a lawyer, but never took up practice, preferring to work on maps with his father. After Willem’s death, Joan continued to publish both his father’s and his own maps. He also assumed his father’s position as hydrographer for the Dutch East India Company. Towards the end of his life, Joan would dramatically expand his father’s Atlas Novus (1635), turning it into his own masterpiece, the Atlas Maior (1662-72).

Condition Description

Minor wear.

References