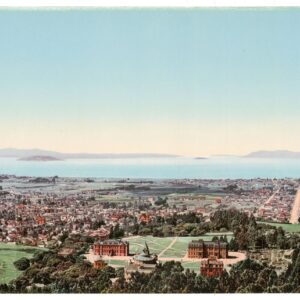

Gold Rush California’s main harbors: including the state capital of Vallejo, the rapidly expanding city of San Francisco, and New York on the Pacific.

Straits of Carquines and Vallejo Bay / Anchorage off Sacramento City / Depot of the Pacific Mail Steam Company, Benicia / Vallejo and Mare Island Strait from the U.S. Coast Survey / Anchorage off San Francisco / Anchorage off New York of the Pacific

$550

1 in stock

Description

In the middle of the 19th century, Northern California experienced a building and demographics boom unlike few others in history. The trigger, of course, was the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in the Sierra Nevada foothills, which from 1849 drew thousands of hopefuls from all over the world to Northern California. Over the next years, the coastal towns of this region flourished, growing exponentially from the massive influx of people. Among the first waves of immigrants to arrive were the prospectors and soldiers of fortune, but in their wake followed savvy businessmen, who realised that there were fortunes to be made in the supply chain of the Gold Rush.

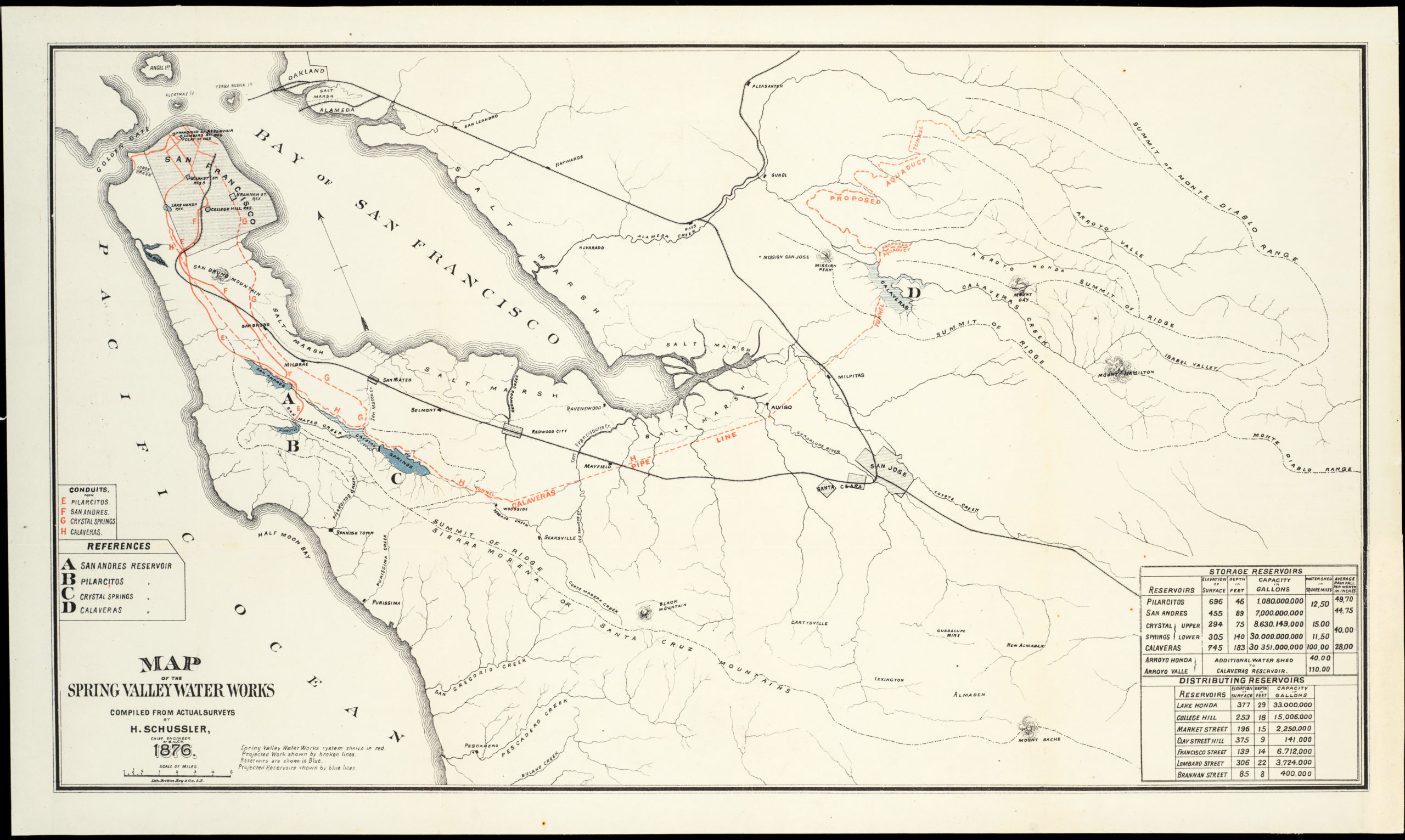

This charming chart essentially consists of five distinct maps (and one inset) showing the harbour and anchoring facilities at some North California’s largest arrival hubs at the time. San Francisco was of course primary among these and is indeed found at the center of the lower tier. It si notable how the previously sleepy town of Yerba Buena already was being transformed into an urban metropolis and the economic engine of California. This transformation is evident from the systematic expansion of city blocks onto the reclaimed water front.

The largest maps are dedicated to the anchorages in and around Vallejo, the regional capital at time. The largest map, in the upper right corner, shows the Straits of Carquines, leading from Southampton Bay to Vallejo itself. A second map show the Mare Island Strait. Mare Island fronts Vallejo and only a narrow natural canal separates the island from the city and mainland. Navigating this approach was dangerous for pilots with no experience of the area, and so a close-up of the Mare Island Strait (essentially the approach to Vallejo harbour) is included immediately below the Carquines map.

In the lower right corner of the sheet, we find a map of ‘New York of the Pacific’. This odd name refers to the town of Pittsburg, located in the delta of the San Joaquin River, near Sacramento. Sacramento itself, today the political and legislative capital of California, has also been included in the upper right corner of the sheet. When this map was published, it had been less than two years since the town’s formal foundation in 1848. Back then, it was still known as Sutter’s Fort, after the illustrious Swiss pioneer of the California Gold Rush. The natural beauty of the location, in the lush river valley of the San Joaquin River, prompted the initial Spanish explorer of the region – one Gabriel Morage – to name the region Sacramento, after the Catholic sacrament. Following the explosive growth of this settlement during the Gold Rush, it was John Sutter’s son who decided to change the name of the town from Sutter’s Fort to Sacramento.

The inset in the Carquines Strait map is also intersting, in that it provides an easy overview of Benicia in the northern part of San Francisco Bay. In 1850, this was the hub of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, which was founded in 1848 by a group of New York businessmen and gradually became the dominant company connecting both passengers, mail, and freight between New York City and San Francisco. The company and site became so important for Northern California’s connectivity to the rest of the world, that between 1853 and 1854, it served at the state’s official capital.

In sum, we have a most charming sheet from one of the most important years in the history of San Francisco, of California, and indeed of America. It was designed to facilitate the mobility of both goods and people, and shows just how rapidly the American West could transform itself, given the right motivation. As such, it is both a result of, and an enticement for, the massive influx of new people to this remote part of the world.

Ultimately, this is an astounding little chart of early American entrepreneurship, dating to perhaps the most intense entrepreneurial period in US history.

Cartographer(s):

Cadwalader Ringgold (August 20, 1802 – April 29, 1867) was an officer in the United States Navy who served in the United States Exploring Expedition, later headed an expedition to the Pacific Northwest and, after initially retiring, returned to service during the Civil War. During 1838–42, he was third in command of the United States Exploring Expedition in the Pacific, commanding Porpoise from 1840 at the invitation of the head of the project, Charles Wilkes. He carried out surveys of Antarctica, the South American coast, the Tuamotu Islands, Tonga, New Zealand and the Northwest Pacific coast of North America.

Ringgold was promoted to commander on July 16, 1849 and began the definitive survey of the San Francisco Bay region, suddenly important because of the discovery of gold in the area. Ringgold both built on previous surveys, most notably Frederick Beechey’s 1833 chart, and undertook a new series of triangulation and azimuth efforts, beginning at modern-day Pittsburgh, CA (then known as the ‘New York of the Pacific’). After the California surveys, Ringgold helped Navy officials choose a location for a dockyard for the Navy’s Pacific station. It later became the Mare Island Navy Yard.

In 1851, Ringgold published a series of charts, views, and sailing directions for the entrance to San Francisco Bay and the inland waterways of gold rush California. The charts paint an important picture of the region during a time of tremendous change.

Condition Description

Expertly laid on Japanese tissue paper; left margin completed.

References

Woodbridge, p. 42-4; Cowan p.533; Howes R303; Kurutz 536e; Streeter 2679 (1st ed).