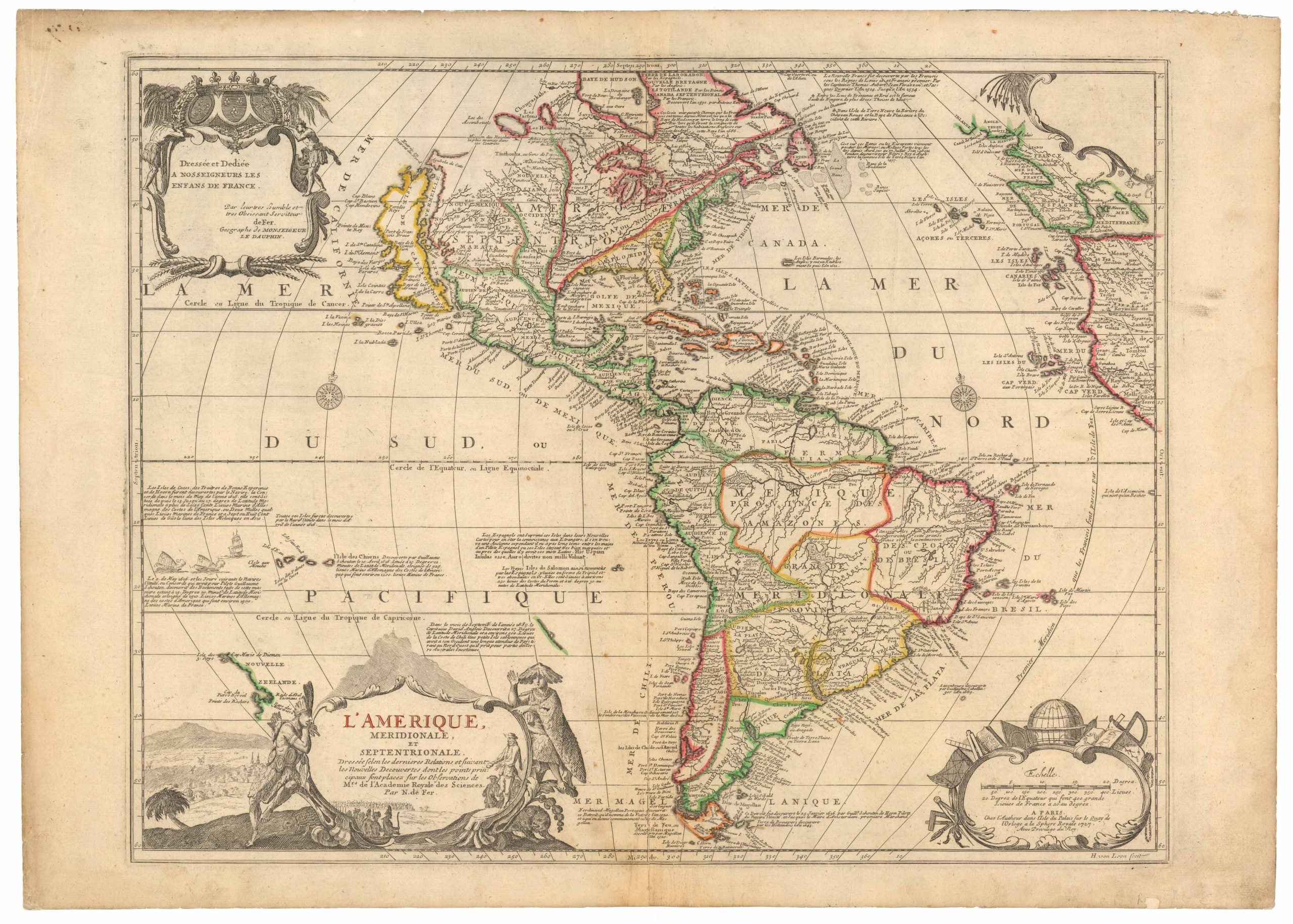

The largest and finest cartographic depiction of the island of California ever made.

La Californie ou Nouvelle Caroline, Teatro De Los Trabajos Apostolicos De La Compa. E. Jesus En La America Septe…

Out of stock

Description

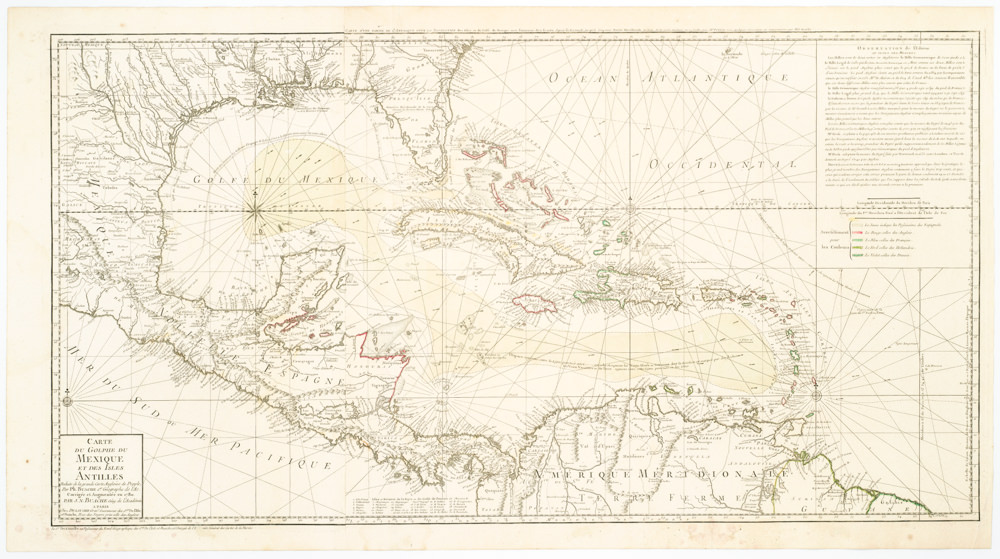

This exquisite and scarce map, made even rarer by its fine original coloring, was published in Paris in 1720. The maker, Nicolas de Fer, was one of the most prolific and influential French cartographers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, who worked for the French King and dauphin (crown prince).

The map depicts the most iconic cartographic myth in the European exploration of the Americas: California as a large island. This notable misconception impacted the accuracy of mapmaking for centuries, and full acceptance that California was part of the continental mainland was not achieved until the mid-18th century.

But why ‘Nouvelle Caroline‘?

We can actually start at the eastern edge of the map, where we see the great Mississippi River emptying into the Gulf. At first, its position seems somewhat anachronistic, as it follows an antiquated 17th-century notion of the Mississippi Delta located far to the west. Cartographers began rejecting this configuration after French explorer Sieur de la Salle navigated the entire lower river in 1682. Yet De Fer’s choice to position the delta further west was, in fact, a keen political move executed in service to his patron, the dauphin. By positioning the Mississippi so far west as to include it in this map, he automatically implies a significantly enlarged French Louisiana, even if it remains unseen.

The French were gradually beginning to encroach on the silver-rich regions in Upper Mexico, which at that time belonged firmly to New Spain. But a great upheaval had recently taken place in Spain, altering the entire political landscape of Europe. When the Spanish King Charles II died in 1700, this closed the chapter on the powerful dynasty of the Spanish Habsburgs following a long period of decline. When power subsequently transferred to Charles’ nephew, Phillipe of Anjou, who became Philip V of Spain, it passed from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons, to which the French kings belonged. It was almost a personal victory for De Fer, as Philip was the son of the French dauphin, who in turn was De Fer’s main patron.

A political element of cartographic land grabbing is echoed in the map’s title, which refers to the island as ‘California or New Carolina’ (Nouvelle Caroline). This bold new proposal for an alternate name was loaded with political meaning. Following the Spanish succession, some still challenged Philip’s claim, just as some feared an amalgamation of French and Spanish interests and power in the New World. De Fer’s maps were part of the counter-propaganda, touting the ambitions of his patrons as fact to exaggerate their global influence. While the term ‘California’ was very much tied to the envisioned island, renaming the entire region Nouvelle Caroline (New Carolina) would make borders more fluid and national ownership less defined.

Beneath the title, De Fer has included extensive text that constitutes an invaluable record of late 17th century missions and Indian villages in this remote part of the New World. The inclusion of this text helped cement De Fer’s map as a seminal contribution to West Coast cartography. The mapmaker seems to have been well aware of the importance of this annotation, as he surrounded it with fascinating vignettes depicting scenes of Native American life and the abundance of the land. He further compliments these scenes with depictions of fauna in the lower-left corner, including an aardvark, a sloth, and a pelican or spoonbill set around the scale bar.

Census and details

La Californie ou Nouvelle Caroline was published in the Atlas ou recueil de cartes gegraphiques. It is not only one of the most significant depictions of the California island theory but also its largest separate (i.e. regional) representation on a printed map. It is essentially an enlarged and far more focused version of his Californie et Nouveau Mexique, published twenty years prior in L’Atlas Curieux ou le Monde.

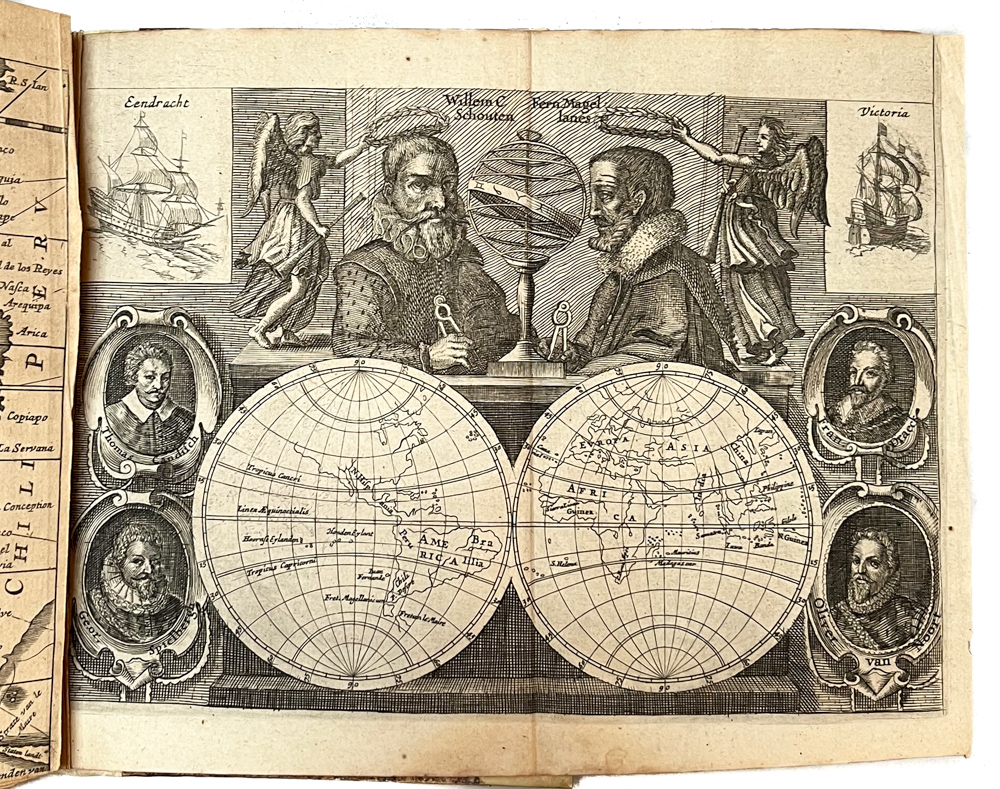

De Fer’s California maps drew on information provided by the Jesuit missionary, Father Eusebio Kino, who traveled throughout the region in the 1680s and 90s and made extensive observations, including the compilation of his own maps. We know that Kino was a significant source because the map’s title is taken directly from his original expedition notes, and important discoveries made by Kino – such as the mouth of the St. Thomas River, discovered in 1684 – have been copied directly onto De Fer’s map from his original. The source is hardly a secret: De Fer uses the inset text in the upper right corner to note how his work was drawn from a map that came via the Viceroy of New Spain to the Academie de Sciences in France. The text also provides a history of California’s exploration and subjugation up until 1695 – including the initial discovery of Baja California by Hernan Cortes – further underscoring the original author.

De Fer made several significant changes for the present map. He plots more than 300 towns and villages, including many locations on the mainland and in what today is known as New Mexico and southern Arizona. The toponyms generally confirm the influence of Father Kino. Among the many places listed, we find the ruins of Casa Grande, identified by Kino in 1694 and appeared on this map for the first time. Important towns like San Diego, Santa Fe, and Mexico City are noted clearly, if not prominently. We even see the first inkling of the settlements that soon would grow into Tucson and Phoenix. The spelling of many of the place names also changed on this new map, just as De Fer incorporated the first Indian toponyms along the Gila River.

While the southern coastline is relatively accurately documented, there are almost no place names present along the northern mainland or on the eastern side of the island, reflecting how little was known about this region at the time. Along California’s exterior coast, we do find some toponyms, in many cases related to the coves and inlets that ships would have frequented. Yet even at this early stage, we are already seeing multiple toponymic references to Saint Francis (San Francisco in Spanish) in the island’s northern part.

Turning to the toponyms of the northern interior, we find Gran Quivira, which refers to the legend of Cibola or the Seven Cities of Gold, supposedly discovered by the Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in 1539. While we know this terminology from many iconic early West Coast charts, like Cornelis de Jode’s famous map of the Northwest Pacific (1593), the myth had such pervasive power that the notion persisted well into the 18th century. In this case, it has even been complimented by a second quasi-mythological eldorado reference in the toponym Gran Teguaio Coqui. This term originates from the Benevides Memorial (1630), which describes it as rivaling Quivira in wealth.

Context

Between 1500 and 1747, confusion ensued over whether or not California, previously documented in medieval folklore as a mysterious island filled with an abundance of gold, was considered part of a series of various mythical islands in an unknown ocean. The “island theory” was perpetuated by Spanish explorers, including Juan de la Fuca, who suggested in reports published in 1592 that the large opening identifying the mouth of Mexico’s Baja peninsula joined a grand bay in the northern part of the continent.

In 1622, Henry Briggs produced a map based on these reports and the travels of Samuel Purchas. Published in London, Briggs’ map was accompanied by an article that referred to California as a large island off the coast of Newe Spaine. This “island” appeared to have a rough and rocky coastline, complete with smaller islands offshore. Brigg’s map became the standard outline for depicting California’s insularity and was copied and incorporated onto the maps of influential publishers and geographers throughout Europe.

Father Kino would eventually dispel the Island of California myth when he discovered Baja California was indeed landbound. Father Kino published this insight in Paris in 1705, some fifteen years before our map was issued, quickly becoming the authoritative source for rejecting the island hypothesis. The notion stubbornly persisted despite Kino’s publication of his latest observations and map. In addition to influential French cartographers like Nicolas de Fer and Philippe Buache, one of the great English mapmakers of the period, Herman Moll, remained convinced of California’s insularity. He even went so far as to claim that he had met sailors who had circumnavigated it. Soon, however, even the most ardent defenders would have to yield when Ferdinand VII of Spain decreed California to be a peninsula in 1747.

Cartographer(s):

Nicolas De Fer (1646–1720) was a French cartographer and geographer who also worked as an engraver and publisher. He was renowned for his massive output and his pleasant visual designs. He was the son of a Parisian cartographer and began apprenticing at an early age. By twelve, however, he shifted his apprenticeship to the closely associated field of engraving – a move his father no doubt encouraged, as it might enhance his competitive position on the market with his son as a trained engraver.

De Fer’s father died in 1673, but Nicolas did not take over the company until 1687, at which point it had been virtually run into the ground. Nevertheless, Nicolas had a knack for business and soon turned things around. By 1690, he was so successful that he won employment as the official geographer to Louis, Le Grand Dauphin of France, and son of the reigning French king, Louis XIV. Soon after, with support from the Spanish and French courts, De Fer was appointed the official geographer for King Louis XIV. In 1720, shortly before his death, he was even appointed royal geographer to Philip V, king of Spain.

De Fer’s popularity in the Bourbon royal circles was primarily due to his appreciation of the propagandistic effects of strategic cartography. But no doubt his keen sense of aesthetics helped as well. Whatever the case, his maps were hugely popular, well-funded, and widely distributed. He was impressively productive, publishing over 600 sheets from his atelier and covering everything from town plans to world maps. Many of his maps rode the political conjunctures of the age. Hardly would a territory have been won or surrendered before De Fer’s atelier was working on a map delineating the new realities.

Condition Description

Excellent.

References

McLaughlin, California as an Island 196 .

Tooley, Printed Maps of America 83.

Tooley, California as an Island 83.

Wagner, Cartography of the Northwest Coast 517.

Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West 102.