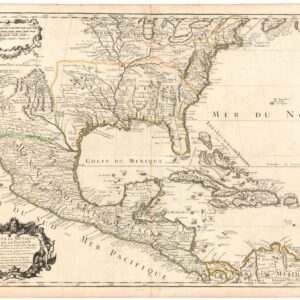

Hutawa’s mysterious 1863 map of the American West: an icon in St Louis publishing history and a forerunner of the Santa Fe mining industry.

Map of Mexico & California Compiled from the latest authorities by Juls Hutawa Lithr. Second St. 45 St, Louis, Mo. 2nd Edition 1863

Out of stock

Description

Second 1863 issue with New Mexico boundaries and ‘NEW MEXICO’ label overprint.

This is Julius Hutawa’s rare pocket map of the American West, published in St. Louis in 1863. Two central aspects make Hutawa’s map one of the most period-specific views of America ever created, each of which merits closer investigation:

- It has a fascinating and rather mysterious publication history pertaining directly to the mid-western hub of St Louis.

- This 1863 edition promotes the development of a mining industry around Santa Fe at the closure of the Civil War, highlighting the region as the latest emigrant destination.

An early product of the St. Louis publishing industry

A key element that makes this map especially interesting and collectible is its publication history and relationship with the Midwestern hub of St. Louis. St. Louis is among the earliest urban settlements in the American interior. Built on Spanish territory by French fur traders in 1764, it straddles the confluence of the great Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Following the region’s incorporation into the United States, it soon became the most widely used setting-off point for travelers heading west. It is consequently no surprise that St Louis soon developed a strong printing and mapping industry despite its frontier atmosphere. Among the entrepreneurs engaged in this industry were two German brothers that had arrived in St. Louis as far back as 1833.

This map builds on an earlier version issued in 1847 at the height of the Mexican-American War. It was published as a supplement to the October 1st edition of the Saint Louis Missouri Republican, and represents lithographer Julius Hutawa’s first serious endeavor in cartography. Sadly, not a single copy of this original map has survived (Wheat 1942). Still, a new edition of the map was issued the following year, carrying the 1848 date and noting ‘St. Louis’ as the place of publication in the imprint.

From this point on, the map’s publication history becomes slightly fuzzy. Nevertheless, we can be certain that Hutawa published two states of this map with the date 1863:

- A version in which the geography is fascinatingly out-of-date, more reflective of the situation a decade earlier, in 1853: after the Compromise of 1850 had cemented the border between Texas and New Mexico, but before the 1854 Gadsden Purchase had completed the final U.S. landgrab to the south.

- The current example, which includes the Gadsden Purchase and has the outline of the Territory of New Mexico superimposed over pre-existing territorial delineations.

At first glance, the superimposition of New Mexico can appear somewhat confusing. To clarify the situation, Hutawa decided to label it in large letters after printing. Unlike the rest of the map, which is lithographed, the New Mexico label was added typographically (i.e. stamped on top of the lithograph).

The Compromise of 1850 saw Texas lose most of its western extremities to New Mexico and Utah. The upper Rio Grande Valley and the region around Santa Fe now belonged to New Mexico rather than Texas. If we zoom in on this particular region, the valley around State Fe stands out as the most densely labeled region on the entire map. In general, the map is remarkably accurate regarding New Mexico, pinpointing towns, villages, and mines; delineating travel routes; and charting the distribution of Indian tribes in the region.

The Rise of the Santa Fe Mining Syndicates

New Mexico had transformed into a new center of prospecting and mining during the 1850s, with large commercial mining firms excavating in areas like Santa Rita, Cerillos, and the Organs. This nascent industry had suffered tremendously during the difficult first years of the Civil War but was now at the precipice of a dramatic expansion. Much of it centered on Santa Fe, and Hutawa may thus have updated the 1863 version of his map to further the interests of certain parties there. Indeed, it may even have been funded to attract more workers to settle in the area.

New Mexico and the upper Rio Grande Valley became a nexus of the Civil War in the West. Once Texas seceded, the Confederacy was eager to push New Mexico and Southern California in that direction as well. The Unionists, on the other hand, were equally determined to keep New Mexico as an integrated part of the country, thus ensuring that the Confederacy remained territorially incoherent.

On top of this dynamic was the covetous eye of Texas on those parts of New Mexico that lay east of the Rio Grande. In particular, Santa Fe was deemed a crucial node to either win or hold. Indeed, when General Sibley invaded Santa Fe, it was at the head of a Texan army with a distinct sense of an underlying mission to retake the Rio Grande Valley. In her book on the history of mining in New Mexico, Christiansen quotes a contemporary observer of the events as stating: “The destruction caused by the Texas invasion in 61-62 had a most disastrous effect upon this country. The invaders consumed its substance, caused the loss of almost the entire mining capital, and much injured the agricultural interests“.

Once hostilities in New Mexico ended, the region experienced a virtual boom in immigration and investment. And it was not just prospectors and miners that were coming; opportunities for commerce, trade, and homesteading were also part of the appeal. The year 1863 lay at the cusp of that boom, an evolution that continued in full force throughout the 1860s, creating one of America’s richest mining complexes in a matter of decades.

A lot of what was driving this rally to New Mexico came in printed form: from spellbinding tales of the frontier, scientific reports on themes like mineralogy, and the plethora of maps and guidebooks catering to travelers and dreamers alike. With all this rapid growth in mind, it is not surprising that Hutawa recognized the enormous commercial opportunity that lay in adapting his map with a new focus on New Mexico.

Conclusion

In summary, this fascinating map is a testimony to the beginning of mining syndicates in New Mexico and an exciting reminder of how transitory and formative the mid-1800s were for the United States. It is ultimately the winning trifecta of historical context, an exciting publication history, and the embedded New Mexico micro-history that makes Julius Hutawa’s map one of the strangest and more collectible American maps on the market.

Census

Copies of Julius Hutawa’s Map of Mexico & California are located in a number of institutional holdings throughout Europe and the United States. Due to the complicated publication history outlined above, most of these are listed as the 1863 map but constitute different states of the map with the same date. The OCLC lists copies at the Bibliotheque nationale de France (494807499) and at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, and Cornell University (16413127). The same institutions also hold undated copies predating the 1863 edition (51072341).

Cartographer(s):

Julius Hutawa was among the early German immigrants to Saint Louis, arriving with the Berling Society in 1833 along with his brother Edward. The brothers were soon engaged in lithography and publishing, and among the maps created by Julius Hutawa are Frémont and Nicollet’s Map of the City of St. Louis (1846), Map and Profile Sections Showing Railroads of the United States (1849), Map of the United States Showing the Principal Steamboat Routes and Projected Railroads Connecting with St. Louis (1854). They also published city views.

Condition Description

Backed on soft archival Japanese tissue paper; flattened. Minor loss, spot blemishes, and discoloration along the old fold lines.

References

The present map is a new issue of a map that first came out in 1847 (Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West 547; Vol. III, p. 46; Wheat, Maps of the California Gold Region 46n, noting a supposed 1848 version, in the Bibliothèque Nationale, which actually has no date, no New Mexico handstamp, and no coloring, although it does have printed “2d edition”).

References to 1863 map: Eberstadt 160:228. Graff 2026. Howell 52:439; 440 (both are Streeter’s copies). Rumsey 0335.001 (identical to this copy).

Paige M. Christiansen 1974 The Story of Mining in New Mexico. New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources: Socorro, NM.

Carl I. Wheat

1942 The Maps of the California Gold Region, 1848-1857: A Biblio-cartography of an Important Decade. Grabhorn Press: San Francisco (no. 46).

2004 Mapping the Transmississippi West 1540-1861. The Institute of Historical Cartography: San Francisco (no. 564).