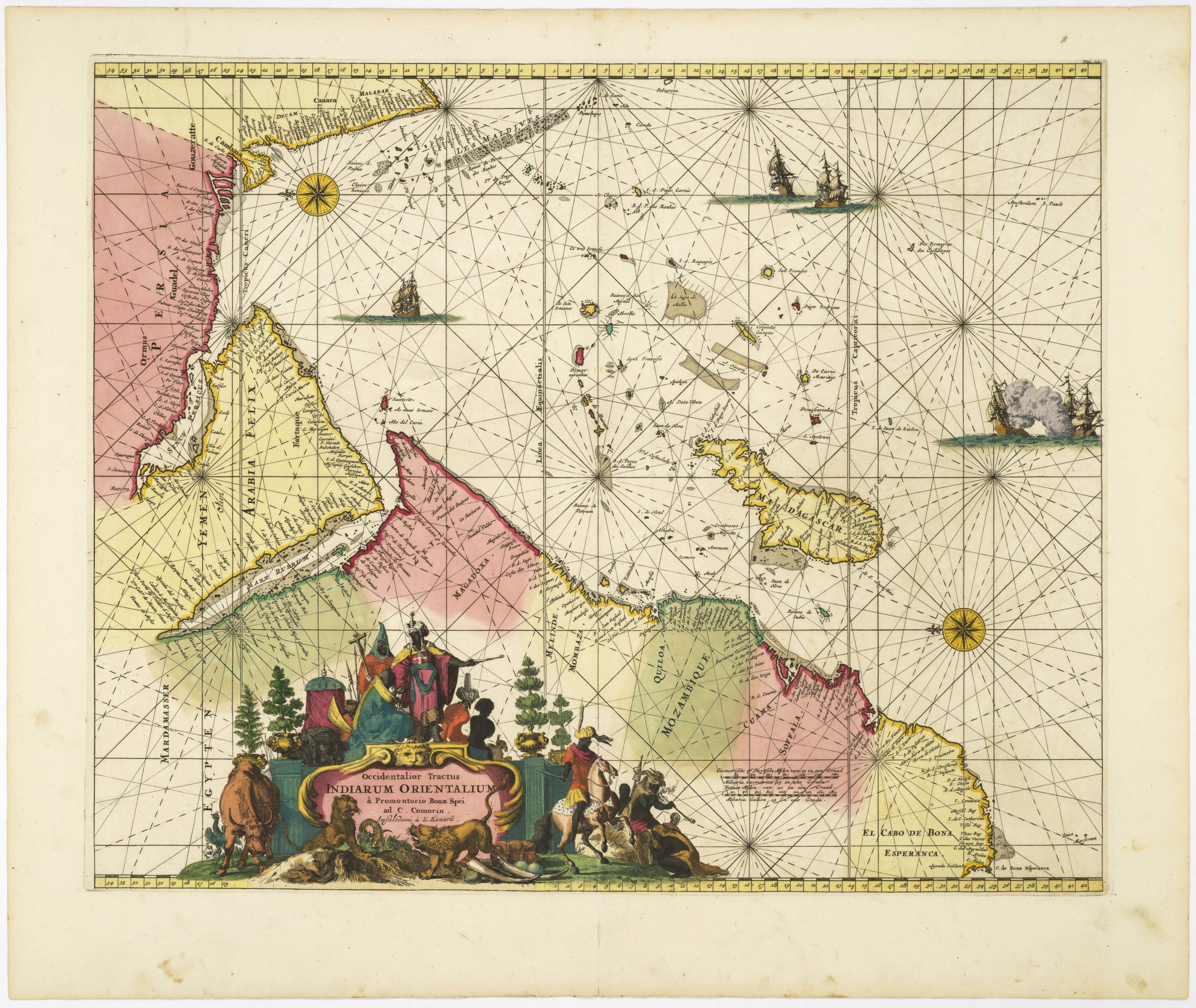

Linschoten’s gorgeous 16th-century chart of West Africa and the Southern Atlantic.

Typus orarum maritimarum Guineae, Manicongo & Angolae ultra Promentorium Bonae spei susq…

Out of stock

Description

Linschoten’s map of West Africa and the South Atlantic encapsulates the daunting challenges that cartographers faced in the 16th century. Voyages of discovery, early colonial ambitions, and perceived prospects for trade have all been embedded in this exciting work. Unlike his contemporaries, Linschoten actually visited many of the regions depicted in his seminal maritime atlas, the Itinerario, a tome that was decisive in kicking off the Golden Age of Dutch maps.

Here at Neatline, Jan Huygens van Linschoten (1563-1611) is one of our favorite cartographers. There are many good reasons for this, not least of which is his charts’ revolutionary accuracy and exceptional beauty. But it runs deeper than that. Linschoten changed mapmaking – both as a science and as an art – and we consequently consider him one of the fathers of modern cartography.

Here is Linschoten’s spectacular chart of West Africa, one of several coastal maps of Africa included in his outstanding cartographic achievement, the Itinerario, from 1596. The sheet is a copperplate engraving, measuring 54 x 40.25 cm (21.3 x 15.8 in). It features vivid hand-coloring and almost no foxing or spotting. It has a handsome appearance and elaborate ornamentation.

The map is a nautical chart that treats us to a depiction of the continent’s southwestern coastline. The visible terra firma stretches from the so-called ‘Slave Coast’ of the Sahel region in the north to the Cape of Good Hope in the south. Fronting the African landmass is most of the South Atlantic, including many islands present there. Despite being an essential part of the map, this oceanic space is used efficiently for a magnificent title cartouche and masterful vignettes of ships and sea monsters. The engravers exquisitely frame the cartouche with stylized griffons, perched birds, and other symbols of abundance, and the Portuguese royal coat of arms crowns it.

The maritime sphere surrounding the cartouche and vignettes is subdivided by a rhumb-line grid interconnecting at multiple nexuses and anchored in two beautiful compass roses (32 and 16 points, respectively). Between these, we also find an elaborate scale bar with both German and Spanish nautical miles defined. That the rhumb lines indeed were meant for navigation is echoed in the invisible inclusion of northeast Brazil on the left fringe of the map. In doing so, Linschoten provides an elegant and easily discernible scale to his map, but he also ensures that this particular sheet works within a broader framework of oceanic navigation and global geography. Running across the map as a whole, and situating us further globally, are the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn. Along the bottom of the map runs a beautiful profile vista of the islands of Ascension and St Helena.

Linschoten’s maps are, in part, famous for their beauty. In most cases, the masterful hands that created them belonged to the Dutch brothers Arnoldus and Henricus van Langren. The Langren Brothers were esteemed engravers who originally came from Utrecht but set up shop in Amsterdam during the 1580s (Keuning 1956). In this particular case, we are treated to the work of Arnold Langren, as indicated in the bottom appendage of the large title cartouche hovering in the Atlantic. Arnold Langren also engraved a matching chart of Africa’s southeastern coast for the Itinerario, including Madagascar and parts of the Indian Ocean. Combined, these two charts provided one of the most detailed and accurate renditions of the African coastline produced to date, including the problematic passage of its southern cape.

While the West African coastline was one of the earliest frontiers explored by Portuguese explorers, much of it was still largely unknown in the 16th century, in part because the Portuguese kept their navigational insight to themselves. European cartographers depicting Africa still drew on the old Ptolemaic model as a foundation and then built on that using whatever sporadic reports and testimonies they could get their hands on (including those of foreign writers like the Berber diplomat Leo Africanus, 1494-1554).

Depicting southern Africa at this level of detail was, in other words, a most unusual accomplishment for the late 16th-century map industry. There were simply not enough good sources on which to draw. But van Linschoten had served directly under the Portuguese Viceroy in India and had in this capacity both seen and copied a wide range of hand-drawn portolan charts on which the Portuguese based their navigation and India trade. Otherwise, these were kept from Europe’s naval powers and guarded as ‘state secrets.’ The enormous influence that Portugal commanded on the global stage at this time is, among other things, seen in the consistent mix of Portuguese and local place names along the depicted littoral. When Linschoten left Portuguese service and later published his maps, these would become decisive in opening up the Indian Ocean to Dutch traders, who soon would out-compete their Portuguese rivals.

The toponyms along the African coast are indeed like pearls on a string, underlining that the engine of expansion first and foremost was driven by wind and sail. Perhaps more unusual is the fact that the African interior has also been relayed in considerable detail for the period, albeit less reliable information than that along the coast. Regions are subdivided using color-coding, and the early Portuguese presence in Angola is clearly seen in the density and nature of coastal toponyms here.

Something similar can be said of the Sahel coastline or Bight of Benin, which would come to be known as the Slave Coast over the next century. Among the interior embellishments, we find numerous great cities depicted alongside topographical features such as mountain ranges, great rivers, and enormous lakes. The lesser-known regions, where little is represented, have in turn been endowed with the splendid wildlife that inhabited Africa and lived in the imaginations of many Europeans. The bestiary includes an elephant, a rhino, a lion, and a pair of enormous snakes. And on the great Lake of Zaire (Zaire Lacus), we find two mermaids enticing viewers with musical instruments.

In sum, this is not only one of the most beautiful maps of West Africa to have been produced in the 16th century but also a milestone in the history of Africa’s cartography. It is a testimony to the most significant period of exploration in human history and heralds the immense human tragedies of colonialism and slavery that would mark the 17th century for posterity. Yet, despite the grim undertones, it remains a striking early example of the new aesthetic heights that Dutch mapmakers would raise cartography to in this century.

Context is everything

Jan Huygens van Linschoten was the son of an innkeeper who grew up hearing the stories of travelers and sailors. Being born to a well-off family permitted him an advanced education, and living in the Dutch port of Enkhuizen allowed him the opportunity to gain experience at sea. When the Low Countries were struggling to gain their independence from Spanish dominion, van Linschoten traveled to Spain to work with his brother in Seville and eventually ended up in Lisbon. For a young man looking for adventure and opportunity, he could not have chosen a better place, and from this time forward, he began to build his cartographic career.

The Portuguese had spent the 16th century establishing a dominant hold on the sea route around Africa to the East. This superiority gave them a near-monopoly on Indian Ocean trade, with Spain as their only serious rival. Throughout the Indian Ocean littoral, the Portuguese constructed and manned coastal forts in order to maintain this monopoly. In 1505, the Portuguese King cemented his ambitions in the region by establishing the Portuguese State of India (Estado da India Portuguesa). Initially, the capital was at Cochin (Kochi) in southwestern India, but it was soon moved further north to Velhas Conquistas in Goa, where a Portuguese government continued in some form to 1961.

In the bustling and cosmopolitan Goa, van Linschoten would settle. During the journey and once he arrived, van Linschoten was meticulous in keeping extensive notes on the peoples, customs, and geography of the regions through which he traveled. He studied and copied portolans, sorted through reports, noted down gossip and rumors, spoke to merchants and mariners, and would presumably sketch down maps of places he visited or stories he heard. Years later, this unique and personal dataset would help elevate his work above his contemporaries and make his atlas one of the most important travel accounts from this era.

In January 1589, van Linschoten left Goa and began the long journey back to Portugal. En route, his ship was pursued by an English fleet and lost its cargo in a storm while anchored off the Azores. After this, van Linschoten was persuaded to stay and help recover it, and so he spent two years on Tercera, slowly preparing his notes from Goa for publication. He eventually arrived in Lisbon early in 1592 and proceeded to sail home to The Netherlands shortly after that.

Like many cartographers of his day, van Linschoten entertained an ambition of publishing his studies and insights. Once back in Europe, he set straight to the task, and in 1596 his opus magnum was published. Known as the Itinerario, this multivolume publication collated all of the Portuguese (and some Spanish) sources on sailing the Indian Ocean and presented them in a coherent and usable fashion. At the time of its appearance at the end of the 16th century, the great Dutch publishing houses were masters at marketing, and Amsterdam-based printer Cornelis Claesz knew that the addition of maps would be great for sales. Linschoten hired the famous Langren Brothers to engrave the maps as he compiled them. The account of his experiences stands as one of the essential travel works of the period.

Cartographer(s):

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563 – 8 February 1611) was a Dutch merchant, trader, and historian who traveled extensively through the East Indies under Portuguese influence and served served six years as bookkeeper for the Archbishop of Goa (1583-89). He is credited with publishing important classified information about Asian trade and navigation that was kept as closely guarded secrets of the trade by the Portuguese.

In 1596, Linschoten published his Itinerario (later published in English as Discours of Voyages into Ye East & West Indies), which graphically displayed for the first time in Europe detailed maps of voyages to the East Indies, in particular the Indian Subcontinent.

Condition Description

Discoloration, some wear, repair visible on verso.

References

Keuning, Johannes 1956 The Van Langren Family. Imago Mundi 13: 101-09 (http://www.jstor.org/stable/1150245).

![[South Africa] Photograph panorama of Cape Town, c. 1870](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Screen-Shot-2022-12-18-at-11.22.15-AM-300x300.png)