A spectacular and historically important 18th century wall-map of the Republic of Genoa.

A Topographical Map of the Republick of Genoua, Taken from the Celebrated Map by Chaffrion…1764 / To the Right Honourable James Steward Mackenzie, Lord Privy Seal of Scotland, One of His Majesty’s most Honourable Privy Council, and Late His Majesty’s Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipoteniary to the King Of Sardina. This Map is most Humbly Inscribed…

$4,400

In stock

Description

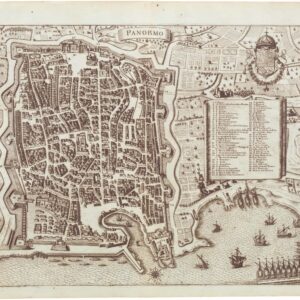

In many ways, this beautifully composed chart of the Republic of Genoa epitomizes why we love maps. It is deeply evocative, not only of a time in which Italy remained segregated into republics and principalities, but indeed of the dramatic landscapes of the French and Italian Rivieras that once constituted the Republic of Genoa. It is thus that each time we engage with this map, different details seem to jump off the page. Sometimes the first thing that comes to mind is the natural topography: the way the mountains of Liguria press right up to the sea, giving shape to the dramatic and picturesque port towns of Portofino, Sanremo, and Monaco, and the fashionable beach towns of Antibes, Nice, and Cannes.

Other times, this is a map that makes us think about power — both gained and lost — for at the center of the map we find the heart of the Republic: the great city of Genoa. The Republic of Genoa was a dominant maritime power and far-reaching mini-empire that existed for almost seven centuries. And yet, the end was near, and before the turn of the century, Napoleon would erase it from the map. In that sense, this map constitutes an historically important documentation of a key region in Europe on the cusp of change.

Details

This particular example of Dury’s chart was designed as a folding map, being sectioned and laid on linen, and presented in a fine slip case with an embossed title and gilt lettering. The map measures an impressive 75 by 42 inches (190 x 106 cm) and boasts an incredibly detailed topographic landscape, seemingly with every peak, river valley, and mountain pass meticulously drawn onto the map. Throughout, we find villages, towns, and cities, as well as many of the roads that connect them, all marked accurately on to the map.

The Republic itself is subdivided into smaller territories delineated by color-coding. Along the top of the map we find its rather extensive title written in four languages: English, French, Italian, and German. The already lengthy title is further elaborated with a dedication in English found inside the elaborate cartouche in the lower left corner of the map. The imagery surrounding the cartouche is characteristic of its time and contains abundant symbolism referring to trade, exploration, colonization, science, and the arts. It is crowned by cherubs and an angelic figure, adding the religious component to the mix as well.

In the center of the Ligurian Sea we find two important inserts depicting the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, which also fell under the auspices of the Genoese Republic. Throughout history the island populations of the western Mediterranean have been ferocious in their resistance to external occupation. Even though Corsica was subsumed under the Republic of Genoa already in 1347 and remained under her control for centuries, at the time our map was published this subjugation was slowly coming to an end. Consequently, the legend for Corsica denotes only military encampments and points of engagement from an extremely confrontational summer in 1739. Four years after this map was published, in 1768, Corsica finally broke her bonds with Genoa for good.

The legend on the Sardinia insert refers to specific metallurgical resources on the island and reveals one of the reasons that mainland powers often had such interest in it. Sardinia’s subjugation by Genoa is something of an historical irony in that in the very bitter end, it was be the Kingdom of Sardinia that finally and unequivocally brought the Republic of Genoa to a close.

The Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa was a maritime polity on the north-western coast of Italy (Liguria) that lasted from the 11th century to 1797. During the late Middle Ages, it was one of the major trading powers in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. It also dominated trade with the Far East and funded the iconic expeditions of Marco Polo. From the 11th century to 1528 it was officially called “Compagna Communis Ianuensis” and from 1580 “Serenìscima Repùbrica de Zêna” (the most serene Republic of Genoa), but it was known colloquially by names like la Superba, la Dominante, la Dominante dei mari, and la Repubblica dei magnifici. The boastful adjectives were not without merit, as Genoa navigated the difficult waters of conflict and trade so well that during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it became one of the most important financial hubs in all of Europe.

Genoa was primarily a maritime republic, and it stood as Venice’s eternal rival for domination of the Mediterranean (even today, its coat of arms is included on the flag of the Italian Navy). In 1284, the Genoese Navy vanquished the Republic of Pisa in the battle of Meloria. The prize was dominion over the Tyrrhenian Sea, and the city prospered further as a result. As in Venice, the sovereign of the republic was the Doge. This elected position was originally endowed for life, but after 1528 each Doge would (at least formally) only be elected for two years. In reality, however, the Republic was an oligarchy ruled by a small group of merchant families, from which all of the Doges were selected.

Throughout its history, the Genoese Republic established numerous colonies in the Mediterranean and Black Sea region. These included local annexations such as Corsica and Monaco, but were soon expanded to encompass the entire Mediterranean and beyond. Examples include the Aegean islands of Lesbos and Chios, which came under Genoese rule from the 14th century and remained that way until 1462 and 1566 respectively. But the Genoese also established trading colonies at much more distant locations.

Most famous perhaps was the large Genoese colony in Galata, just outside the walls of Byzantine Constantinople. During the Turkish siege to win the city in 1453, the Genoese saw which way the wind was blowing and assisted the Turks in winning the battle by providing them with crucial resources and intelligence on the communications of Constantine XI and his court. The reward for their betrayal was that the Genoese, at least for a time, could continue their mercantile activities under Ottoman rule as well. Genoese settlements were established as far away as Southern Crimea, where a colony flourished between 1266 and 1475.

With the end of the Renaissance and the arrival of the early modern age, the Republic lost many of its colonies and had to shift its interests and focus to banking. The process of converting the economy from colonial trading to banking was not without challenges, but in the end it proved a very successful strategy. Even after the fall of the Republic in 1797, Genoa remained one of the centers of capitalism and banking in the world.

Officially, the Republic began when Genoa became an autonomous municipality in the 11th century. It ended when it was conquered by the First French Republic under Napoleon Bonaparte. This saw Genoa replaced by a new Ligurian Republic, which in turn was re-annexed by France in 1805. When Napoleon was exiled to Elba in 1814, Genoa proclaimed itself a republic once again and for a short time Genoese rule was restored to the region. But it was only brief. In January 1815, only nine months after the proclamation, the Kingdom of Sardinia annexed the entire Ligurian coastline, including Genoa.

The Chafrion precursor

Cartographically, one of the elements that makes this map so collectible is that it draws very directly on the iconic and extremely rare 1685 map by Giuseppe José Chafrion. Chafrion was a Catalan military engineer and surveyor who for a period worked for the governor of Milan. Chafrion’s map of the Genoese Republic and its Ligurian coastline is seen as pivotal because prior to this, little to no coordinated regional cartography had originated from Genoa for almost 150 years: essentially since the time of Agostino Guistiani (see Quaini in references). Instead, the world was forced to rely on maps by foreign cartographers such as Jansson, Seutter, and Homann — maps that lacked the accuracy and detail of Chafrion or Dury.

At times, the Genoese authorities would even attempt to actively block the compilation and publication of regional maps of their Republic from within. One such incident regarded Chafrion’s Carta de la Rivera de Genova con sus verdaderos confines y caminos (1685), which the Genoese authorities perceived as a threat to their military and diplomatic standing in Europe. The Genovese officials failed to block its publication, but managed to keep its circulation was limited. The fact that Andrew Dury could draw on this iconic chart is one of the main reasons that his map became, and still is, such a huge success in cartographic circles. Dury’s map itself became an inspiration to many 18th and early 19th century mapmakers, starting with Yves Gravier’s mural map of Liguria from 1784.

Census and publication history

The map was compiled by Andrew Dury on the basis of Jospeh Chafrion’s map and published by Andrew Dury and Wiliam Faden in London in 1764.

OCLC notes at least seven copies of this map in institutional libraries across the world.

Cartographer(s):

Andrew Dury was a British map-maker and print publisher who operated out of Duke’s Court on St. Martin’s Lane in London during the second half of the 18th century. Even though he was an accomplished cartographer with major commissions, he never reached the level of success attained by contemporaries such as Thomas Jefferys or William Faden. Consequently, his beautiful maps have become quite rare and are today sought-after collectors’ items.

Dury’s name is normally associated with Major James Rennell’s large India maps, but he was also responsible for Revolutionary War-era plans of Boston and Philadelphia, as well as a series of maps related to the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-74.

Condition Description

Segmented and laid on linen, with original slipcase. Some panels slightly darker than others.

References

Frescura, Bernardino. Genova e La Liguria, Nelle Carte Geografiche, Nelle Piante, Nelle Vedute Prospettiche: (Primo Contributo per La Storia Della Cartografia Ligure), 1992.

Quaini, Massimo. Cartographic Activities in the Republic of Genoa, Corsica, and Sardinia in the Renaissance.