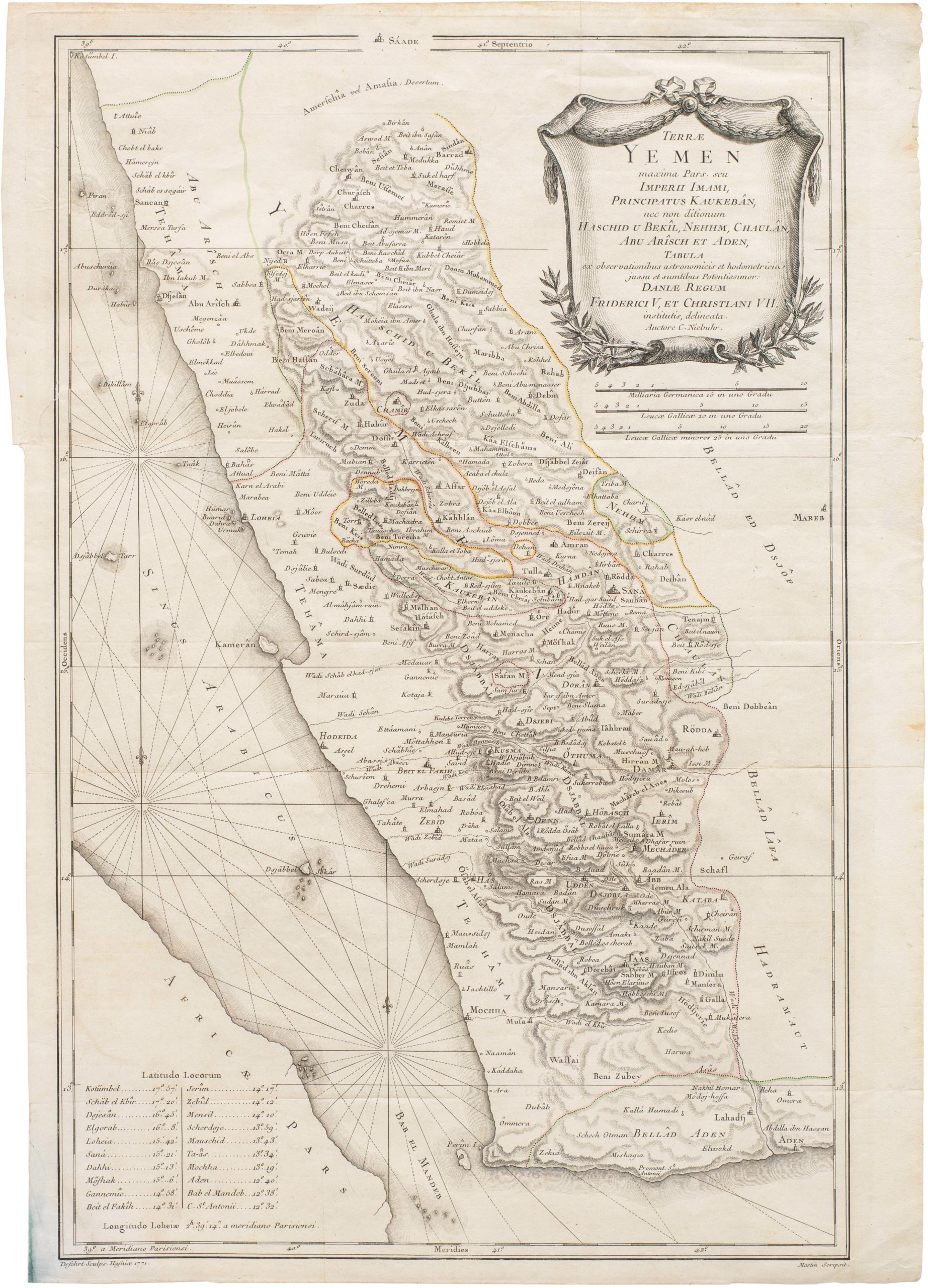

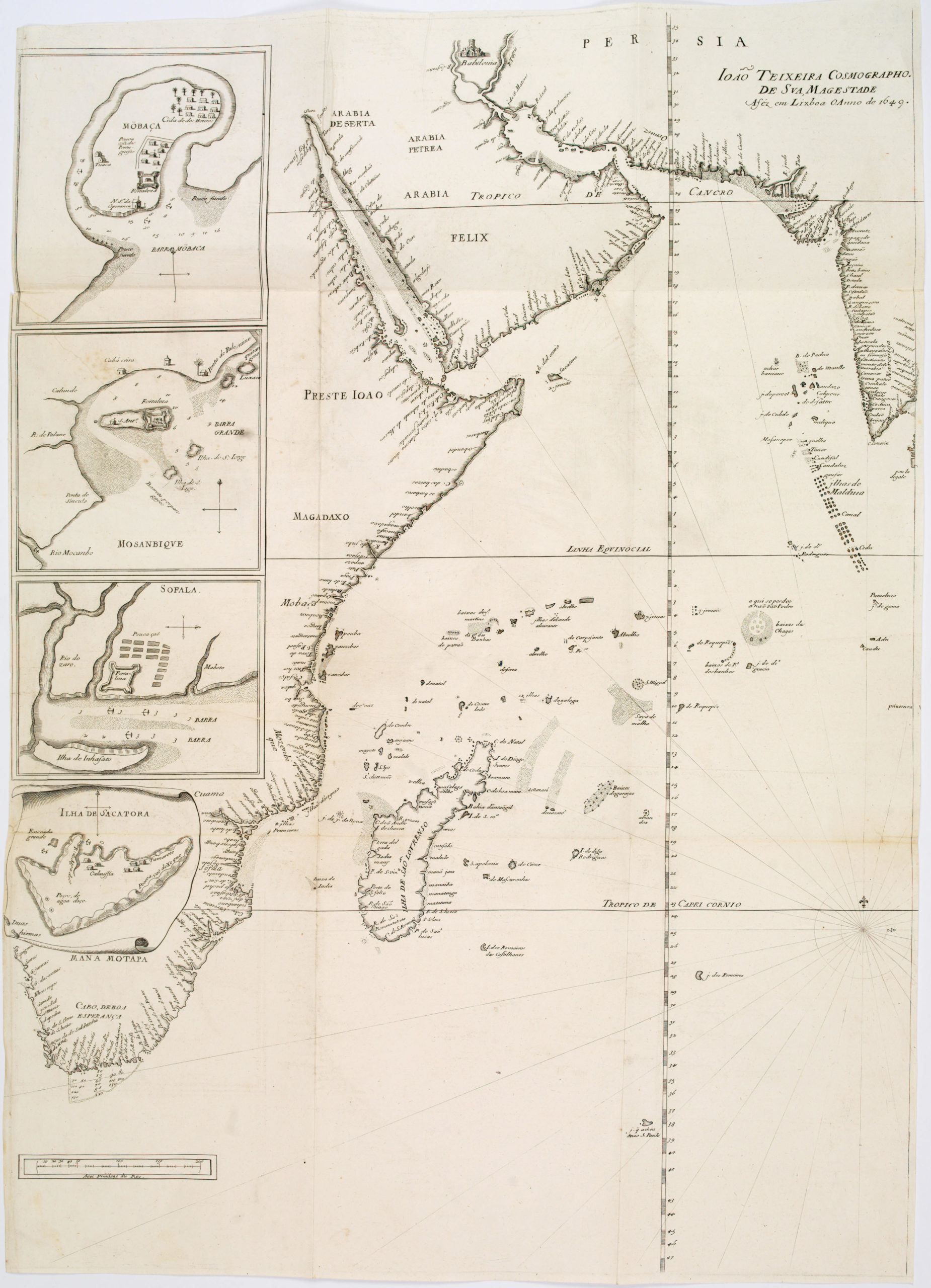

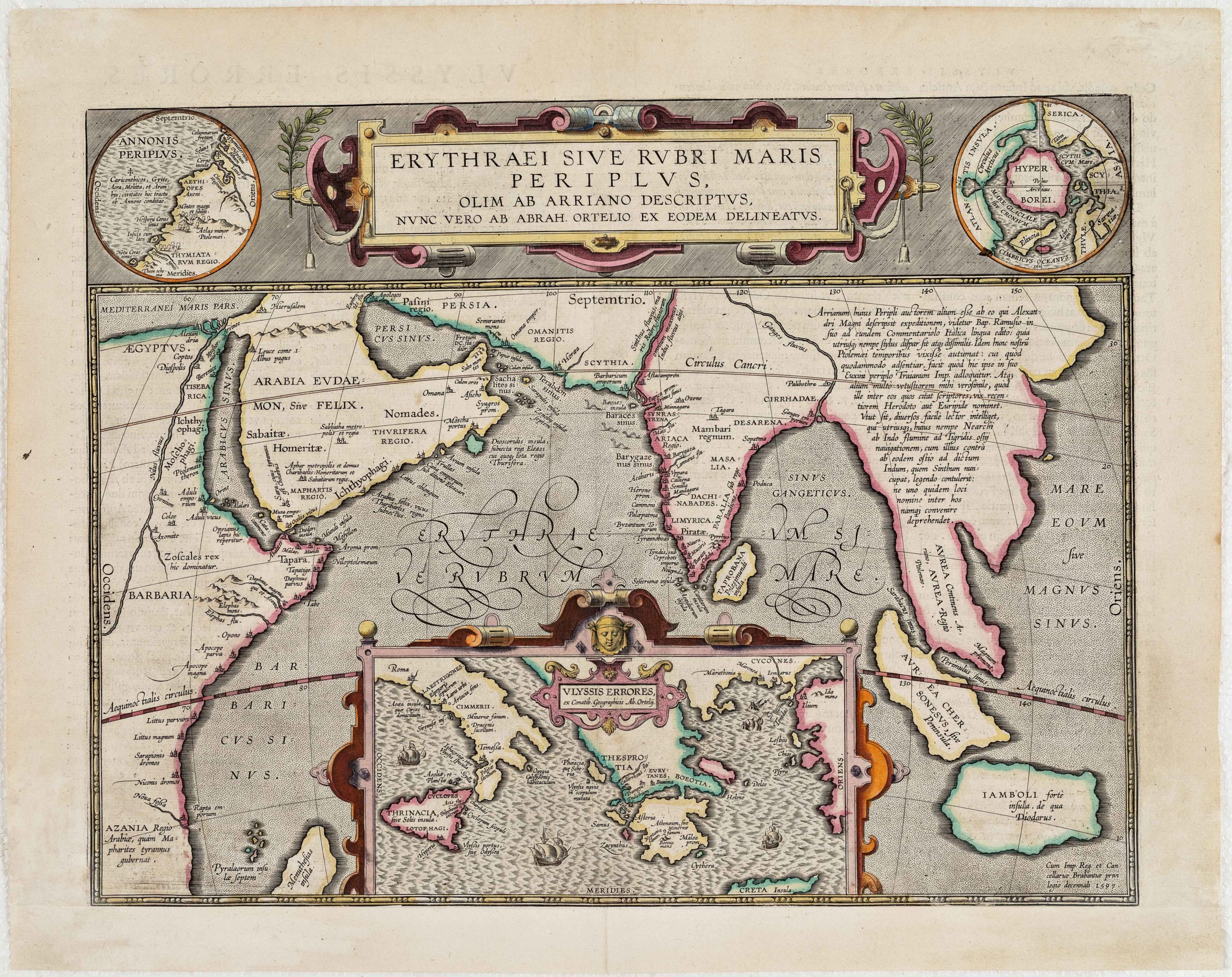

16th century map of Arabia on a Ptolemaic projection.

Tabula Asiae VI

$475

1 in stock

Description

Fine example of Ruscelli’s map of the Arabia Peninsula, with details from the east coast of Africa, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the mouth of the Euphrates, and the southwestern coast of Persia.

The Arabian Peninsula covers more than 1 million square miles and is comprised of the modern states of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. It is one of the largest regions in the world with no navigable rivers, a circumstance that made exploring and mapping its interior a difficult endeavor. The first map of the Arabian peninsula to be printed in Europe was in the 1477 edition of Ptolemy. By Ptolemy’s time, Greek sailors had sailed around the Arabian coast and were familiar with port towns. However, its interior remains largely unmapped until the 20th century. The northern part of the peninsula tended to be mapped more accurately because it was closer to populated lands and more frequently traveled, but the interior of Ptolemaic maps are almost completely fanciful, including the mountain ranges, river systems, and lakes. The cartographic errors are probably a mix of depicting stories told to sailors about what lies inland and the desire to fill space common in pre-18th century cartography.

This map is from Ruscelli’s translation of Ptolemy’s Geografia, which included enlarged maps from Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1548 edition of Ptolemy. Tibbetts calls Gastaldi 1548 the first modern map of Arabia. The shape and orientation is much improved over Ptolemy and coastal towns are represented more accurately. But the cartographic errors and inventions represented in the interior of the Arabian Peninsula are largely continued from Ptolemaic maps.

One especially persistent error (from Ptolemy until it is disproved in 17th century) is the depiction of a large lake (Stag Lago or Stygis Fons) between the Hadhramawt and the Empty Quarter. Tibbetts speculates that these could have been based on the waters of Yemen which flow east into the desert, or the reservoir of Marib (which was known to classical writers). Gastaldi actually plots a second lake for Marib in 1561. The myth of Stag Lago endures on later maps, drifting towards the sea over time, on some maps even becoming a bay.

Cartographer(s):

Girolamo Ruscelli (1518–1566) was an Italian mathematician, polygraph, and cartographer active in Italy during the early 16th century. He was born around 1518 in Viterbo to a family of minor nobility and humble origins. Throughout his life, Ruscelli moved around, living all over Italy. He started in Aquilea, but his work soon drew him to more important centers of learning. He moved first to Padua, and around 1540, he settled in Rome, where he founded his Accademia dello Sdegno. Around 1545, Ruscelli left Rome for Naples, and in 1548 he finally settled in the city that would make him most famous, Venice.

While posterity primarily remembers Ruscelli as one of the most important cartographers of the Venice School, his primary source of income came from publishing – both his works and copying the work of others. While he wrote on a broad range of subjects himself, the works plagiarised from others were often published by his partner, Plinio Pietrasanta. This lucrative relationship lasted until 1555 when Ruscelli was arrested and tried by the Inquisition for re-publishing a satirical poem by Pietrasanta without his formal permission. Any confrontation with the Inquisition was unpleasant enough, but Ruscelli may have been particularly susceptible to pressure because his wife’s family entertained Protestant sympathies. His brother-in-law was burned at the stake in Rome some years later.

The relationship with Pietrasanta had nevertheless soured, and the publishing firm was soon closed. Instead, Ruscelli partnered up with another Venetian publisher, Vincenzo Valgrisi. It was with Valgrisi that Ruscelli published his famous Ptolemaic Geografia in 1561. This atlas contained sixty-nine engraved maps sporting the latest ideas in Italian cartography. Despite containing some of the latest cutting-edge ideas about the world’s composition, Ruscelli’s atlas also drew heavily on earlier works. Forty of the 69 maps in Ruscelli’s atlas were copied almost directly from Giacomo Gastaldi’s Geografia from 1548.

Despite Ruscelli’s fame as a cartographer, he also achieved considerable recognition under his pseudonym Alessio Piemontese. His greatest success in this regard came the same year as his arrest (1555), with the publication of De Secreti del Alessio Piemontese. In this book of alchemy, Ruscelli reveals himself as a true Renaissance man, dabbling proficiently in multiple disciplines at the same time. His ‘Secrets‘ contained instructions on how to make everything from alchemical compounds and medicines to cosmetics and dyes. The work was so popular that it was re-issued numerous times over the next two centuries, and translated into French, English, German, Latin, Dutch, Spanish, Polish, and even Danish.

Condition Description

Excellent.

References

Tibbetts, G. R. Arabia in Early Maps. Ney York, NY: Oleander Maps, 1978.