De Jode’s extraordinary map of Arabia — among the finest maps of the region on the market.

Secundae Partis Asiae.

$7,000

1 in stock

Description

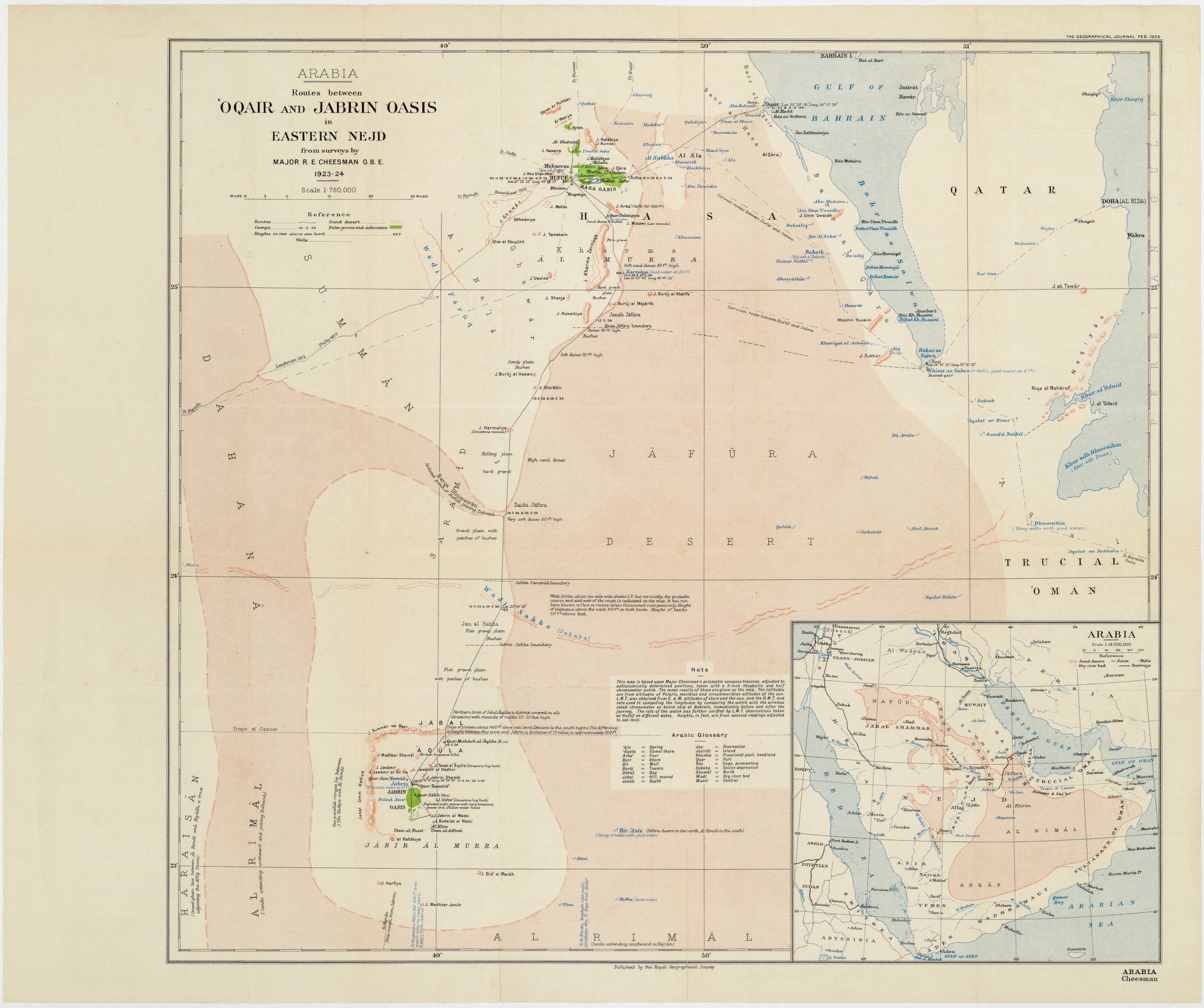

Based on Giacomo Gastaldi’s landmark 1561 map and engraved by Joannes and Lucas Van Deutecum, this is undoubtedly one of the most spectacular 16th-century maps of Arabia. It covers an area stretching west-east from the West Nile Delta to the Maldives and south-north from the Horn of Africa to Damascus.

The geography of the map is a significant improvement over earlier Ptolemaic productions, especially the width of the Red Sea and the shape and orientation of the Persian Gulf. The ‘S’ curve of the Straight of Hormuz is a much more accurate reflection of reality. However, the topography of the interior of the Arabian Peninsula, still a great unknown for European mapmakers, is largely invented. This includes Ptolemaic legacies such as the mythical lake of Stag Lago and newly fabricated mountain systems not delineated by Ptolemy.

The Arabian Peninsula covers more than 1 million square miles and comprises the modern states of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. It is one of the largest regions in the world with no navigable rivers, a circumstance that made exploring and mapping its interior problematic. The first map of the Arabian peninsula to be printed in Europe was in the 1477 edition of Ptolemy. Tibbetts notes that, like other early Greeks, Ptolemy exaggerated the length of Eurasia to the east. The distance between the Red Sea and Persia was too big, and thus Arabia was stretched to fill the gap, mainly because Ptolemy knew the entrance to the Red Sea was very narrow; therefore, he had to make the shape fit.

By Ptolemy’s time, Greek sailors had sailed around the Arabian coast and were familiar with port towns. However, its interior remains largely unmapped until the 20th century. The northern part of the peninsula tended to be mapped more accurately because it was closer to populated lands and more frequently traveled. Still, the interior of Ptolemaic maps is almost entirely fanciful, including the mountain ranges, river systems, and lakes. The cartographic errors are a mix of stories told to sailors about what lies inland and the desire to fill space common in pre-18th-century cartography.

Cartographer(s):

Gerard de Jode (1511-91) was a Dutch printer and mapmaker born in Nijmegen, but working from the metropolis of Antwerp. One of the most competent and reputable Dutch cartographers of the 16th century, he did not fare so well business-wise, as competition was stark and his mercantile sense perhaps not so shrewd. In 1547 he was accepted into the Guild of St Luke’s in Antwerp and began working as a publisher and printer. De Jode quickly gained recognition as an expert mapmaker in a city that was already renowned for its cartographic output. His greatest achievement was a magnificent two-volume atlas entitled Speculum Orbis Terrarum, which came out in 1578. The idea was to create an atlas that could compete with Abraham Ortelius’ hugely popular Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, which had been published to great acclaim only eight years earlier. Despite De Jode’s status and reputation, however, his atlas was not a commercial success. The lack of circulation in 1578 has had a lasting legacy today, as it is now one of the rarest and most sought-after atlases, with only about a dozen copies known to exist.

Despite this lack of commercial success (or perhaps because of it), Gerard began working on a new and revised atlas. For this task, he recruited his son, Cornelis De Jode (1568-1600), as an assistant, and together they compiled another outstanding and innovative atlas entitled Speculum Orbis Terrae, which was published in 1593. Sadly, Gerard de Jode died of old age a little less than two years before its publication, but perhaps he was spared the embarrassment of another commercial failure. Even though the new atlas contained both Gerard’s original maps, it also included several key revisions, and perhaps most importantly, a range of entirely new maps compiled by Cornelis himself.

Like their 1578 predecessors, these 1593 maps are also scarce, especially since after Cornelius’ death, the engraving plates were sold to his competitor, J. B. Vrients (who also owned the Ortelius plates), who assured the complete work was never published again. Thus, while numerous editions of Ortelius were published and survive today, only the 1578 and 1593 editions form part of the legacy of the De Jode family.

Condition Description

Reinforced centerfold, overall excellent. Wide margins. Verso text: Latin. Watermark: two crossed arrows.

References

![[Mısır Haritası / Map of Egypt]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/NL-02391_thumbnail-2-300x300.jpg)