A unique artifact of Gold Rush San Francisco, including one of San Francisco’s most famous buried ships!

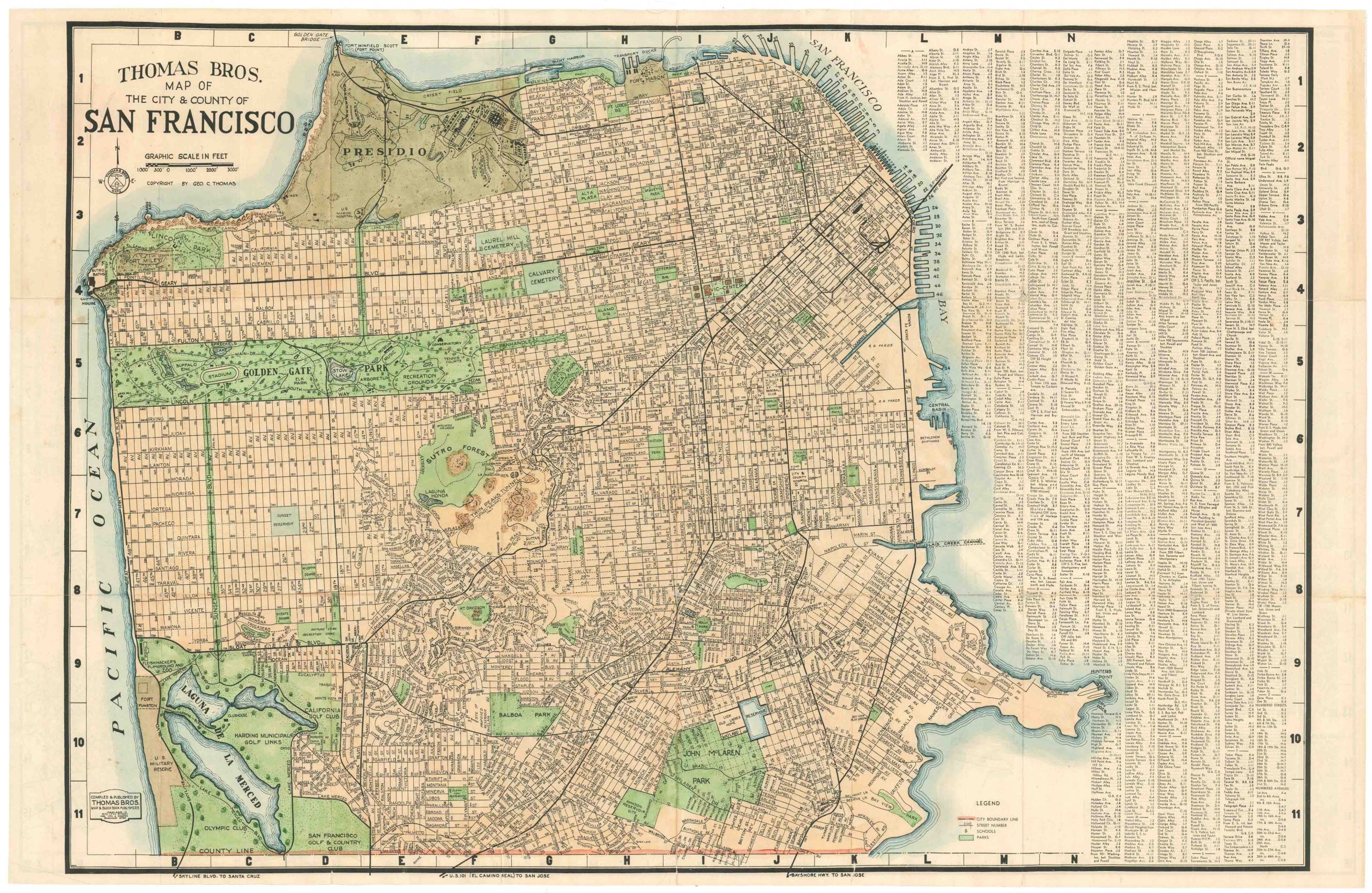

San Francisco. from actual Surveys. 1850.

$75,000

1 in stock

Description

CLICK HERE TO SEE A VIDEO WE MADE ABOUT THIS MAP.

This is an unrecorded manuscript map with annotations in French. It was probably annotated by an early French commission merchant living in San Francisco and was likely sent to New York or Paris accompanied by a now-lost letter detailing the activities of the firm as well as the immense changes taking place in San Francisco during this time. Such a letter might also have described commercial services, operations, and opportunities in San Francisco’s growing French community.

It is often said that the gold diggers didn’t get rich, but the shovel salesmen did. With its excellent natural port and access to the rivers flowing out of the Gold Country, San Francisco grew wealthy with the influx of hopeful prospectors and the outflowing wealth of the gold deposits. This map is an artifact of one of the early San Francisco merchants.

Six numbered labels and an accompanying legend in the lower left indicate the firm’s commercial interests. The legend identifies one residential location, three commercial sites, and two public features of early San Francisco: the old shoreline and the first major wharf.

Each item on the legend can be traced to today’s city. The first four are related to specific properties of the author:

#1 Notre maison d’habitation [our house] — Lot 116 on Dennis St. (near Powell Street and Jackson Street).

#2 Notre bureau et magasin [our offices and warehouse] — unnumbered lot at the Corner of Clay and Leidesdorff Street, between Montgomery and Sansome, which would become Lot 188. These offices were linked to #6 on the map by a public right-of-way that is today Commercial St.

#3 Notre store schip (magasin s/ navire) [Our store ship (warehouse on a vessel)] – This item indicates a point of significant current and historical interest: the site of the ship Arkansas, which is the ship that gives its name to the present-day Old Ship Saloon at the corner of Battery and Pacific streets, within today’s financial district. Combined with the legend’s fifth item, this location is identified as beyond the city’s original shoreline, in what was once the waters of the Yerba Buena Cove. We must remember that San Francisco’s original shoreline was several blocks in from where it is today; this site was part of the process of the city’s expansion.

#4 Terrain appartenant au comptoir [Land belonging to the trading post] Although this site might have been a vacant lot facing an empty field when the map was drawn in 1850, its placement facing a planned open plaza in the city — what would become Union Square — can be seen as a point of importance in the city’s civic structure. It is easy to imagine a merchant touting the site’s value as an exciting future development: a prominent site facing one of the two plazas planned for the city. (The other, farther north, between Union and Filbert Streets, is now Washington Square).

That vision of potential commercial value would have been correct. Today, that lot is the site of an Apple Store, revealing its continued commercial value.

The fifth item in the legend is part of the story of the growth of San Francisco:

#5 Ligne qui designe toute la partie de la ville batie sur la mer [Line showing the whole portion of the city built on the sea] shows the original shoreline of the city and the planned rapid expansion of the city out into the San Francisco Bay.

A good portion of today’s San Francisco stands on land that was once tidal mud flats, a point of sufficient interest that the author of the map noted it, even though, unlike the other items in the legend, it does not have an apparent relationship to commercial activities of the map’s author.

The final item in the legend indicates San Francisco’s first significant wharf, built to meet the rapidly growing commercial traffic fueled by the Gold Rush:

#6 Wharf (quai) bati et qui a pres d’un ½ mille [wharf built which is almost half a mile long] – This is a reference to Central Wharf at the bottom of Market Street, which was approved in May 1849 and became San Francisco’s first “modern” wharf (now the site of the Ferry Building Marketplace and Golden Gate Ferry Terminal). The city merchants and politicians quickly understood the need to develop the waterfront to accommodate the many arriving ships and, first and foremost, a pier to facilitate the offloading of goods.

The Expansion of the City into the Bay—“la ville batie sur la mer” (#5 in the legend)

1850 San Francisco was a true boom-town, having grown from a sleepy village into a sizable city in about one year. In the summer and fall of 1848, after discovering gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills, the town of about 1,000 was nearly depopulated as its residents ran for the hills in search of gold. Two years later, after the 1849 Gold Rush brought gold seekers from all over the world, it had grown to a city of over 25,000—the largest on the Pacific coast of the Americas.

By 1850, as this map shows, most of San Francisco’s downtown was planned if not fully developed, with many of today’s familiar streets already laid out in the city grid, including Market, Mission, and others, while some streets have taken new names over the years, for example, the street between Kearny and Stockton — today’s Grant Ave. — was named DuPont (General and later President U.S. Grant would not earn his fame leading the Union Army for another fifteen years).

It is not easy for a city to grow rapidly and accommodate so many new people. Key to the growth of San Francisco was its eastward expansion, facilitated by the sale and eventual infilling of water lots, shifting the waterfront away from the original shoreline to deeper waters in the bay, a move that the mapmaker has indicated with the line designated #5 in the legend — Ligne qui designe toute la partie de la ville batie sur la mer — dividing the city into parts built on land and parts built “on the sea” by infilling the tidal mud flats.

Such was the delirium that characterized the early years of the Gold Rush that many of the arriving ships, packed with fortune seekers from all over the world, were immediately abandoned upon arrival, not just by their passengers but also by their crews, leaving the ships floating in the bay.

“As stores and dwelling houses were much needed, a considerable number of the deserted ships were drawn high on the beach and fast imbedded in deep mud, where they were converted into warehouses and lodgings for the wants of the crowded population. When the town was subsequently extended over the mud flat of the bay, these ships were forever closed in by numberless streets and regularly built houses of brick and frame.” (Annals of San Francisco).

Thus, as the mapmaker indicates, a large portion of San Francisco, even in the early 1850s, was literally “built upon the sea” (batie sur la mer).

The authoritative study of the early San Francisco waterfront, Gold Rush Port: The Maritime Archaeology of San Francisco’s Waterfront, by maritime archaeologist Dr. James Delgado, demonstrates that the construction of San Francisco as a critical international port was “the culmination of decades of work by a group of mercantile capitalists, who seized the moment, between 1848 and 1851, to alter forever the patterns of global maritime trade.” (Delgado, p. 49). The development of this new American port city on the Pacific was directed by a combined strategy of politicians and merchants to sell off much of the town’s public lands.

Managing the vast influx of people and goods were commission merchants who processed, stored, and eventually distributed goods, constituting in this way a crucial link in an international maritime commercial network that included Central and South America, Hawaii, China, the eastern United States, and Europe. The commission merchants took advantage of abandoned vessels, converting them “into floating or mud-moored buildings, most of them warehouses, linked by pile-supported wharves and structures.” (Delgado, p. 11). Using ships as buildings was “one of the decisive factors in rapidly transforming San Francisco from a village into a working port and major city. The idling of so many vessels was a fortuitous circumstance that provided much-needed warehouses and other protected spaces and enclaves.” (Delgado, p. 60) The ships provided ready-made facilities that were embedded in, and then beneath, the rapidly growing city.

The peak of the storeship era lasted from late 1849 to 1852. In November 1851, the official count of storeships along the waterfront was 148, and their use was also noted in the waters off Sacramento, Benicia, and Stockton (Delgado, p. 85). The last of the storeships was broken up by 1857, but their skeletons remain buried beneath the city. The remains of about 50 storeships are estimated to be buried beneath San Francisco’s streets.

In their day, however, the storeships were built into the expanding land of the city, some becoming offices, prisons, churches, or hotels, like the Niantic, a former whaling vessel.

On this specific map, the storeship (item #3) is outside the original shoreline and shaped like a ship. We wondered whether it would be possible to identify precisely which ship it was, and we found our answer when comparing it to an archaeological map of excavated or known storeship sites. The site marked #3 on the map is presently occupied by one of San Francisco’s oldest operating bars, The Old Ship Saloon, which initially opened and operated in a storeship (hence the name) and is known as the site of one of those old Gold-Rush vessels, the Arkansas.

The Arkansas arrived here from New York on December 20th, 1849, under Captain Shepard’s command, after serving as a packet ship in Liverpool and New Orleans. She was blown aground on Alcatraz and then dragged to the location shown on this map, where it was first converted to a warehouse and then into the bar and hotel known colloquially as ‘Old Ship.’ While the ship itself was buried, the bar continues in its current location.

In short, to our knowledge, we have the only known manuscript map with a contemporary indication of a San Francisco buried ship, and that ship is not just one of the ships buried and forgotten, but the one ship whose memory has been most kept alive by the bar to which it gave its name.

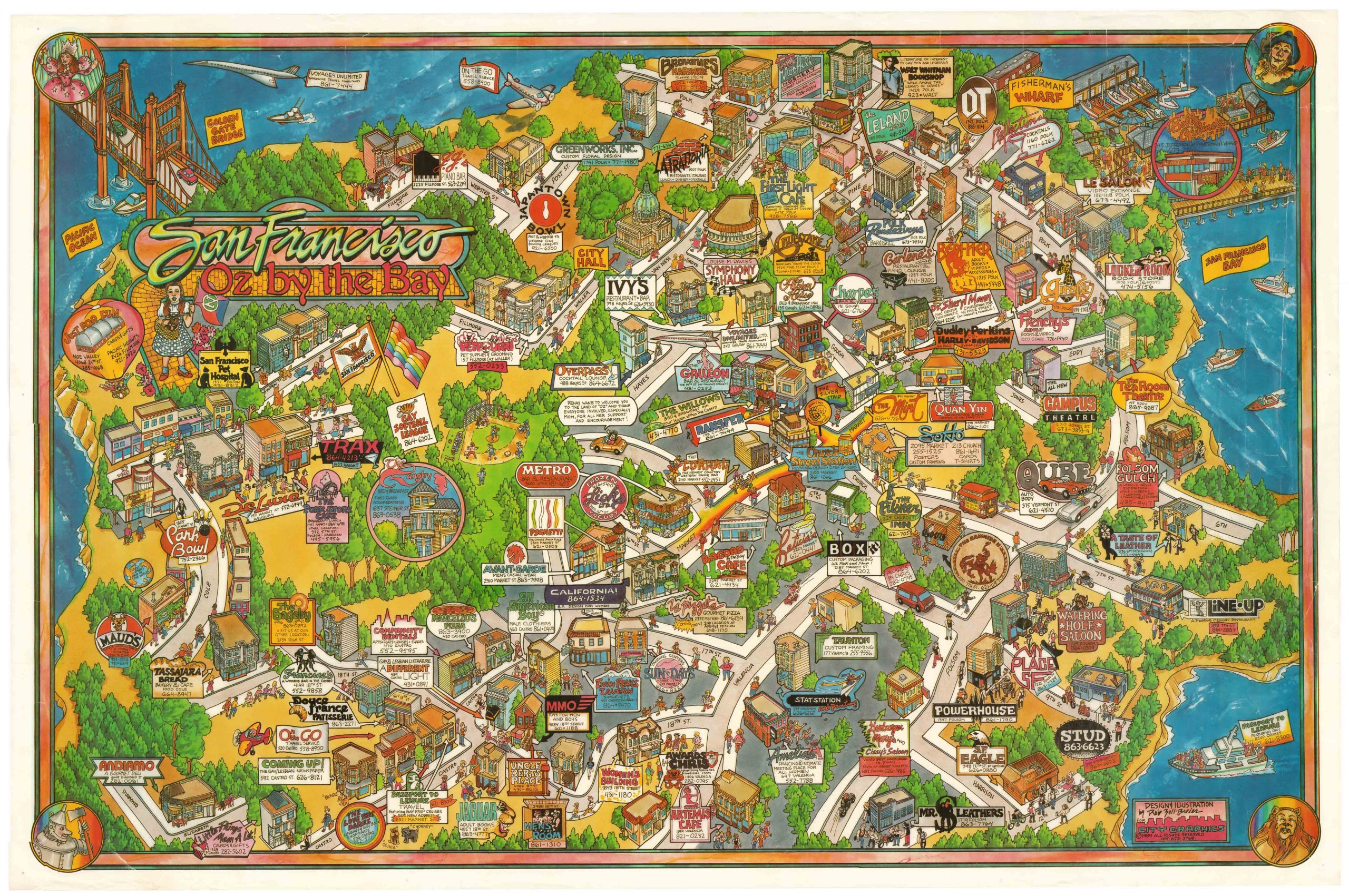

San Francisco’s French Quarter

In the United States, and, indeed, for much of the world, the most important events of 1848 might have been the two developments that shaped California: the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill and the conclusion of the Mexican-American War with Mexico ceding its vast northern territories, making up many of today’s southwestern states, including California. The Gold Rush brought people from around the world to California. However, for Europe, 1848 was the “Year of Revolution,” as many nations of Europe, including France, were engulfed in civil uprising. The domestic turmoil undoubtedly contributed to the number of French 49ers. The impetus to leave everything behind and set out across the globe was tied to the lure of fortune and “escape from endless riots, endemic unemployment, and the collapse of commerce and social privileges” (Chalmers, p. 7).

The French already had an early presence in California (as did many European nations–John Sutter, the owner of Sutter’s Mill, where gold was found, sparking the Gold Rush, was Swiss). The first real immigrant recorded is Jean Louis Vignes, who came from Bordeaux and started a vineyard near Los Angeles in 1831. When the capital of California was still at Monterey, France was represented by a consul.

The French pioneers of San Francisco, 36 in number, arrived on the sailing ship La Maose in 1849. As early as the Spring of 1850, the French operated stores, restaurants, and hotels on Clay Street in the old business section.

The area around Belden Lane and Bush Street would soon become known as the French Quarter, with approximately 3,000 French government-sponsored migrants arriving in San Francisco by the end of 1851. There were several French residents in San Francisco active in commercial enterprises by 1850, with this map almost certainly associated with an effort by one such resident to provide early commercial details of the city and waterfront at a time when few available printed maps were providing sufficient detail.

Identifying the Mapmaker/Who is behind the map?

The map itself is unsigned. While it is presumed to have accompanied other documents identifying the maker, this leaves some doubt about its creator. The site listed at #2, however—“our office and warehouse”—provides crucial clues that lead to our tentative identification of the author.

We are grateful to Dr. James Delgado for these notes:

The annotation of the line of fill and the beach (#5) and the call out of Long Wharf (#6) suggest that the map was accompanied by a letter outlining what was happening in the city at the time and factors influencing his business as a commission merchant. He likely made the point that their shop was positioned at an ideal location. They are essentially at the epicenter of where goods are being landed in 1850 and a concentrated cluster of other commission merchants, auctioneers, and insurance agents. The house and shop off Pacific and Pine (#1) looks to be a rented or subleased part of a larger building. These merchants were at the heart of San Francisco in the period. Through their contacts with various other houses worldwide, they were able to show how San Francisco connected to the emerging global economy of the time. From the house to the office was a five-block walk, largely downhill. It is roughly the same distance to get to the storeship. The parcel on the future plaza, lot 583, is about nine blocks away.

Directly across the street from their office is the storeship Niantic, full of other tenants, one of whom is the firm Godeffroy, Sillem & Company, who have ties to Hamburg, Paris, and London. The storeship (#3), the Arkansas, is at that stage newly beached and not yet the saloon of later fame.

The shop’s location provides crucial clues to the identity of the mapmaker. In both the Kimball City Directory for 1850 and Barry and Patten’s Men and memories of San Francisco, in the “spring of ’50.”, that line of buildings is specifically called out: “On Clay Street Wharf, at the end of Leidesdorff, were the zinc-fronted stories occupied by Ferdinand Vassault, Simmons, Hutchinson & Co., J.J. Chaviteau, Selim and Edward Franklin, and the office of the ‘up river’ steamboats” (Barry and Patten 1873: 102). The Francophone names Vassault and Chaviteau stand out as the likely sources of the map’s French annotations.

Ferdinand Vassault was a New York-born merchant who arrived in 1849 and became a prominent Society of California Pioneers member. He was a commission merchant and ultimately remained in town, investing in various endeavors. He died in the city on January 13, 1900, and his obituary is in the S.F. Call for January 14. Interestingly enough, he also had a connection to the location of the Arkansas; the San Francisco Daly Alta California of July 20, 1850, has an advertisement noting that the company had “removed from Howison’s Pier to the end of Comm. Wharf, Clark’s Point, opposite iron storeship Arkansas.” Their clerk, William F. Rulofson, is listed in Kimball, as is Vassault & Company, at “Comm Whf, Clark’s Point.”

While it’s certainly possible that the American-born Vassault had commercial connections with other French merchants, it is perhaps more likely that the map’s maker was a member of the Chaviteau firm, whose proprietor, John J. Chaviteau, was born in France. The firm, J.J. Chaviteau & Company, is noted as “General Bankers & Com Mchts” at the location marked on the map. Their direct ties to France are revealed by an ad in The Alta on November 15, 1852, that notes they are the “Agent for French Underwriters.” In 1853, when the ship Cachalot arrived directly from Le Havre, one of the consignees was J.J. Chaviteau.

Chaviteau himself may have made the map, or another member of the firm, for example, one Francis Chaviteau, perhaps a brother or other close relative, who is listed in the 1850 Kimball directory as working on the Clay Street Wharf.

Identifying the Map’s Sources

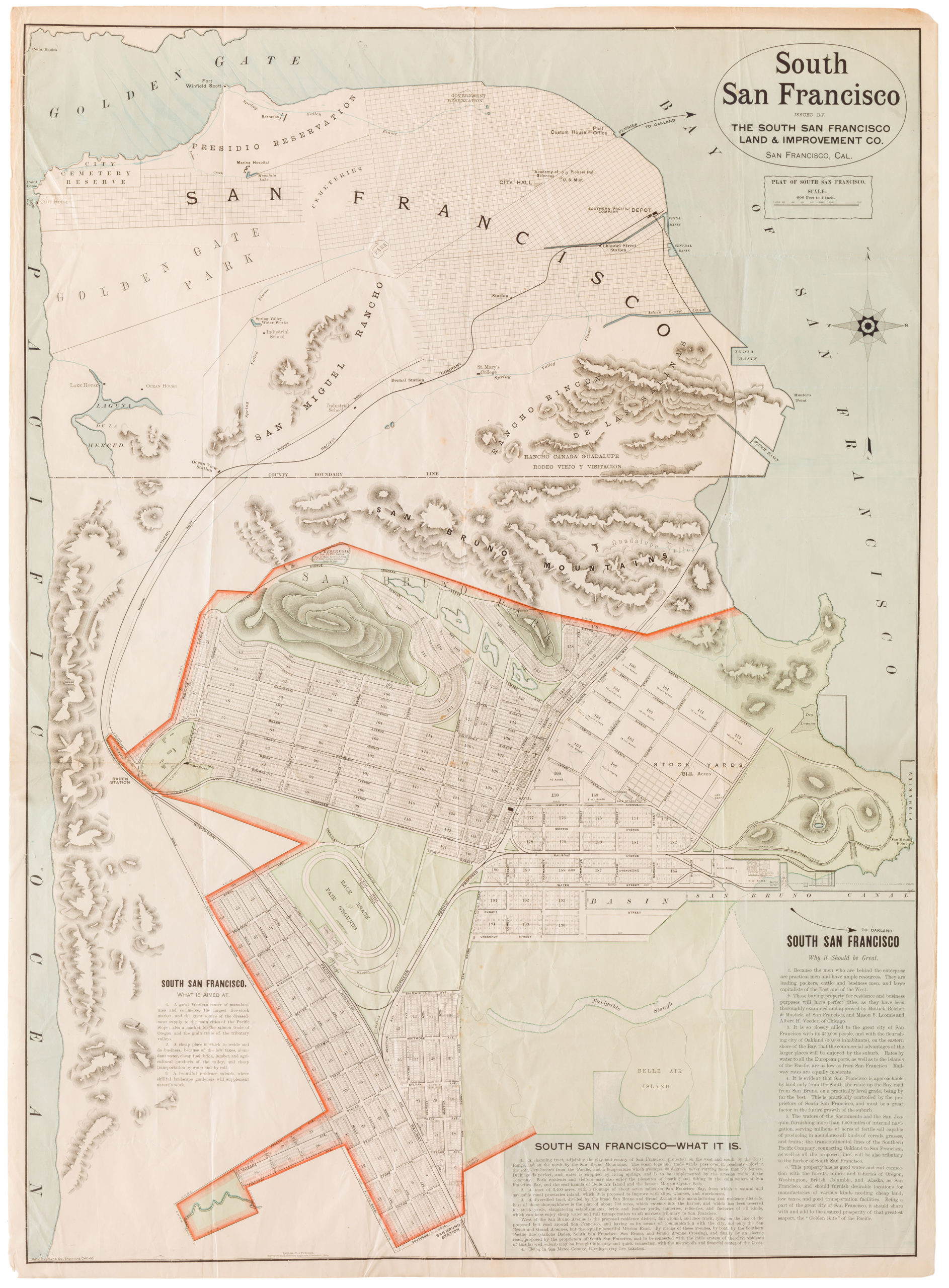

The source of the map is San Francisco from actual surveys. 1850, published in New York by Miller’s Lith. This source map is itself extremely rare, and only one copy is known to exist. It is held by the University of California’s Bancroft Library (Call No. BANC; G4364.S5 1850.M5). We hypothesize that our manuscript map was a draft copy for the New York issue, which perhaps the merchant obtained to illustrate his account.

The earlier, widely available, published maps of San Francisco were produced by county surveyor William Eddy. In 1849-51, Eddy’s The Official Map of San Francisco, Compiled from the Field Notes of the Official Re-Survey made by William M. Eddy, was published in various city reports. A similar version was published separately in 1851 with the title Official Map of the city of San Francisco, full and complete to the present date. Compiled by Wm. M. Eddy, City Surveyor. January 15th, 1851. In the 1851 map, the title has been moved to the left side, and more of the area south of Market is shown. However, the main difference between it and the earlier Eddy (what we call ‘Eddy Classic’) map is that the original shoreline has been colored red; for this reason, it is often referred to as the Red Line Map.

•1849 “Eddy Classic”: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4364s.la002357/

•1851 “Eddy Red Line”: https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~224271~5506363:Official-map-of-the-City-of-San-Fra

The cartography of our map can be interpreted as a mix of Eddy Classic and Eddy Red Line, with one major exception: whereas the two Eddys are oriented north at the top, this map is oriented west at the top. As far as we know, this is one of the earliest examples of an east-west oriented map centered on the waterfront, two years before the 1852 publication of two critical maps that used this framework: Topographical & Complete Map of San Francisco, also by Eddy, and Britton & Rey’s Map of San Francisco, Compiled from latest Surveys & containing all late extensions & Division of Wards.

•1852 Cooke & Le Count / Eddy: https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~291130~90062696:Topographical-&-Complete-Map-of-San?sort=pub_list_no_initialsort%2Cpub_date%2Cpub_list_no%2Cseries_no&qvq=q:eddy;sort:pub_list_no_initialsort%2Cpub_date%2Cpub_list_no%2Cseries_no;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=1&trs=107

Some other points of comparison:

•Rincon Point on this map is drawn in a shape similar to the Eddy classic but adds details not found in either Eddy map, such as rocks off the point and shading to indicate elevation (not seen on an Eddy map until 1852).

•Conversely, it features less detail than Eddy Classic along the coast to the south, omitting water lots for Townsend and Brannan streets.

•In South of Market, our map depicts the outlines of marshlands, as seen on Eddy 1852, and vaguely shows what seems to be Mission Creek.

•Like on Eddy Classic, the southern sweep below Market St. on our map ends at Price St. (8th St.).

•North of Rincon Point, our map is similar to Eddy Red Line, extending to East St.

•Moving northward along the waterfront, our map more accurately plots the location of Fort Montgomery at Battery and Green Streets than any other contemporary published map. Fort Montgomery was part of the defenses erected by Captain John Montgomery at the outset of the Mexican-American War and the American occupation of San Francisco. Battery St. is named for these defenses.

•Our map also offers an interesting cartographic mix relating to the Lagoon Survey, the mysterious early off-axis survey west of Larkin St. outside the original city charter extending roughly from Green to Francisco streets. First of all, Precidio Road [sic] is labeled cutting across the survey. That this was indeed the case is confirmed by contemporary written accounts, but as far as we know, this is the first depiction on a map. Like the Eddy Red Line and Eddy 1852 maps, this map has the Lagoon Survey as 4 quadrants wide, as opposed to the Eddy Classic map in which the survey is 5 quadrants wide. However, similarly to Eddy Classic, the lower right corner overlaps with Larkin St. Finally, the lagoon itself is depicted, which is seen only in Eddy 1852.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Hand drawn on tracing paper, with a bit of foxing and smearing. Local repairs of splits, minor areas of loss.

References

Delgado, James P. Gold Rush Port: The Maritime Archaeology of San Francisco’s Waterfront. University of California Press, 2009.

Chalmers, Claudine. French San Francisco. Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

Frank Soulè, John H. Gihon and James Nisbet. Annals of San Francisco, 1855.

Barry and Patten, Men and memories of San Francisco, in the "spring of ’50.", 1873.