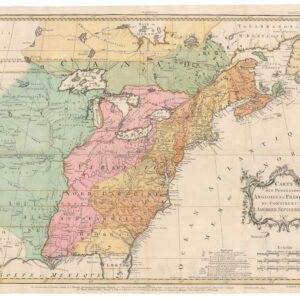

Sayer-Bennet-Mead’s 1775 chart of the Western Hemisphere with Pacific and Arctic routes of exploration.

A Chart of North and South America, Including the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, with the nearest Coasts of Europe, Africa, and Asia

$4,200

1 in stock

Description

Key points:

1. Braddock Mead’s “A Chart of North and South America…” encapsulates the finest qualities of mapmaking in the second half of the 18th century, presenting a remarkable wealth of information.

2. The map was first issued in 1753, and one of its most important features was a repudiation of ideas put forth in an influential 1752 map by French mapmakers De L’Isle and Buache.

3. Our issue was published in 1775 and the revisions are a fascinating mix of improved geography (e.g. the great rivers of North America), and new cartographic myths, (e.g. the rendition of Alaska as an island).

4. The map is also interesting from a political perspective, being a bold statement of Great Britain’s North American territorial claims — the irony of course being that the map was published in the earliest days of the Revolutionary War.

Details

This important, large-scale map of the Western Hemisphere represents the accumulation and refinement of geographical knowledge at the end of the 18th century. It features an encyclopedic overview of key voyages of exploration and cartographic controversies, giving the viewer a window onto both the state of the map publishing business at the time, as well as the European conception of still unknown parts of the earth.

This particular map is the fourth issue of Braddock Mead’s chart of the Americas, issued by Sayer and Bennett of London for the 1776 edition of Thomas Jefferys’ American Atlas, and is thus the most comprehensive revision of this seminal map of the New World. The map was originally issued in six individual sheets, which here have been collated into a single large chart. The map covers both American continents, as well as the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and sections of the Asian, African and European littorals. Among the many innovations offered on this map is a presentation of the latest geographical discoveries mapping terra incognita.

Forming a new narrative for Northwest Pacific cartography

The first edition of this map was published in 1753. It featured an array of new information pertaining to the Americas, especially the Northwest Pacific, ideas about which until then had been heavily influenced by a 1752 map of the region by Philippe Buache and Joseph Nicholas De L’Isle. That 1752 map was problematic because De L’Isle compiled it primarily based on the quasi-mythological account of Admiral Bartolmeu De Fonte, who in 1640 supposedly sailed north from Lima (Peru) until somewhere around the 53rd parallel, where he entered a Rio de los Reyes. From here he was said to have navigated west through a series of waterways until he finally came upon a Bostonian merchant in what is presumed to have been the Hudson Bay. The historicity of De Fonte’s expedition is apocryphal at best, yet both Buache and De L’Isle, and subsequently royal geographer Thomas Jefferys, depicted the geographical information that De L’Isle accumulated as a ‘great probability.’

Feeling the Buache/De L’Isle model to be erroneous, Mead took it upon himself to produce a new and more reliable chart. Keenly aware of the competitive nature of the mapmaking business, and determined to set himself apart from his piers, Mead researched all the latest reports, charts, and accounts available to him in London. It was precisely because of this meticulousness and the systematic, almost scientific approach to compiling various forms of information that Mead’s map quickly superseded that of his predecessors. Mead’s chart of the Americas remained the most important map of the region for years. In fact, it was only after James Cook’s famous expedition to find the Northwest Passage in 1778 that more accurate charts became available. Mead’s competitiveness and professional pride is also reflected in the comparative tables of variations in latitude and longitude between his chart and those of other great cartographers of his day (e.g. Bellin and D’Anville). Other tables provide Spanish coordinates dating as far back as the 16th century, which the English only acquired a few years prior to this map’s publication. We are, in other words, not only dealing with a mapmaker who was extremely meticulous, but also exceptionally well informed.

The six-panel version issued for Thomas Jefferys’ American Atlas took the compilation of variegated data and international discovery to new heights. It depicts the routes of famous “American” explorers such as Baffin and Hudson (his final voyage in which he perished), but also includes detailed accounts of Russian explorers like Vitus Bering, Alexei Chirikov, and Ivan Synd. Not only is it the first time that the Bering Straits have been labeled as such, but moreover the map includes detailed accounts of Bering’s observations and routes while navigating the Arctic and Pacific Oceans.

Legends and islands

Mead’s ingenuity and uncompromising approach to accuracy also meant that whenever possible, he would draw on Asian sources as well. There are references to both Japanese and Chinese geographers and mythologies, including Chinese references to the American coast (Fou-Sang) as well as Japanese references and coordinates for an archipelago of large islands inhabited by a kingdom of dwarves (Ye-Que). The legend of Fou-sang (also Fusang) derives from a Chinese account of a fifth century Buddhist monk who was said to have been blown off course and found himself in a marvelous and strange new land; eventually this land would become identified and located by mapmakers anywhere from Oregon to British Colombia.

Crucial new data was also included on the islands of the Pacific and the Southeast Asian seaboard. In the north, a large archipelago of islands separate the Asian and American continents, the largest of which is named Alaschka. Russian expeditions had identified the American coast already in the 1730s. The rendition of Alaska as an island is a geographical error similar to the persistent notion of California as an island. The decision to render and label it in this way was probably done by the publisher Robert Sayer. The notion of Alaska as an island, found on various contemporary maps, most likely came from Jacob von Strählin, secretary to the Russian Academy of Sciences. He published his own map of the region in 1773 – within a year of the compilation of this issue of Mead’s map – which he based on the observations and notes of Lieutenant Ivan Synd, who had surveyed the region as part of a Russian naval expedition in the 1760s. Strählin’s map was full of errors, so much so that Nelson chastised its inaccuracy after he used an issue of it at sea in 1778.

Returning to Mead’s map, we see that it is covered in notes, tables, and references to provide the viewer with as comprehensive and up-to-date an overview of the regions as possible. In many cases it makes no judgement on to the accuracy of the references, but rather allows readers to make their own assessment. The extensive annotations regarding Bering’s voyages have already been mentioned, but similarly detailed datasets and observations are provided for Hudson Bay and Baffin Bay, again reflecting the extensive research that went into producing this map. In fact, dozens of explorers’ routes are plotted on to the map, including both notes on the journey and illustrations of some of the specific vessels involved in these explorations. A note in the Pacific explains the reasoning behind this: “These Tracks of Shipping are inserted to make known the Navigation of this Ocean, and encourage the discovery of a Passage on this side Northward”.

Another region that was subject to a significant update was the South Pacific. Following the discoveries of explorers like Bougainville and Cook (first voyage), new islands such as Tahiti were added, while others, for example New Zealand and the Falklands, were notably expanded upon. Other islands, such as the Solomon Islands and Pepys Island off the coast of Argentina, are now labeled as ‘Imaginary Isles.’

Promoting British interests in North America

In addition to a great amount of detail concerning discoveries, the map also depicts the latest political subdivisions of North America by demarcating the most up-to-date territorial borders. The map was published at the outset of the Revolutionary War, when the continent was primarily controlled by two great colonial powers of the age: Spain and England. Maps like this one were displays of geographic knowledge, but they were also vehicles of propaganda, political demarcation, and territorial justification. This is seen in both the delineation of territories and in the consistent inclusion of information on who discovered what areas and when.

When we consider this map from a political perspective, we see a map that projects Great Britain’s future ambitions in North America. Between the first edition in 1753 and this edition in 1775, Great Britain had eliminated its greatest rival on the continent: France. The British victory in the French and Indian War (1753 – 1764) gave them much of France’s colonial possessions in America, including the eastern half of French Louisiana to Britain; that is, the area from the Mississippi River to the Appalachian Mountains.

The other clear winner in North America was Spain. France had already secretly given Louisiana to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762), but Spain did not take possession until 1769. Spain did cede East Florida to Great Britain, giving the British control over both and East and West Florida, which they kept from 1763-83. However, Spain still controlled much of the continent, especially Mexico and the West. Mexican Independence was still nearly half a century away, and the Spanish crown maintained a relative dominance along both the Gulf Coast and Pacific coast of California.

And yet, one would hardly know of the Spanish presence in these parts by looking at our map. The only mention of New Spain is the label ‘Mexico or New Spain,’ which stretches from Mexico City down into Central America — that is to say, safely to the south away from British designs in the Pacific West. Furthermore, a very prominent and large typeface ‘New Albion‘ designation at Cape Mendocino, along with references to the discoveries of Sir Francis Drake constitute a direct claim to this region by Great Britain.

The overall result is a confident map, expressing and promoting the colonial interests of Great Britain in North America; the irony is that rather than being on the cusp of expansion, British colonialism was on the cusp of decline, and it would be her very colonies who would gain independence and take her place.

Context is everything

The search for a northwest passage had been active for more than a century by the time Mead published his map. Mead figures prominently in history of how our geographical understanding of this region developed. We have already touched upon the controversial nature of Mead’s immediate forebears, and this map is indeed reflective of an exciting age of exploration, where every month new reports were submitted from all over the world, with mapmakers and geographers scrambling to keep up. Moreover, through its diverse array of information, Mead’s great American chart also demonstrates how competitive the business of cartography was and how the best practitioners applied a scientific approach to the art.

Mead’s new chart represented both a decisive step forward in mapping the new world, as well as an explicit commentary on Buache and De’Isle’s reliance on De Fonte as a credible source. On Mead’s map, the only virtually blank area (including the oceans) is the west Canadian wilderness. The one annotation that is present reveals how important Mead felt it was to counter the French maps. He notes: ‘These parts, as yet wholly unknown are filled up, by Messrs. Buache and Del’Isle, with the pretended Discoveries of Adm. De Fonte and his Captains in 1640’.

Mead started working for Thomas Jefferys, cartographer to George III, around 1750 and probably produced this hemispherical map within the first few years. Mead died only a few years later, whereas Thomas Jefferys went bankrupt in 1765. Publisher Robert Sayer of London, who specialized in the publication and reissuing of maps, subsequently bought many of Jefferys’ plates. In 1770, Sayer teamed up with John Bennet (see bios below) and it was under their patronage that Mead’s map was reissued in the present state. Like Mead, Sayer and Bennet drew on the latest discoveries to produce a truly up-to-date chart of the Americas.

The Sheets

Sheet I: Chart containing part of the Icy Sea with the adjacent coast of Asia and America.

Sheet II: Chart comprizing Greenland with the Countries and Islands about Baffin’s and Hudson’s Bays.

Sheet III: Chart containing the coasts of California, New Albion and Russian Discoveries to the North, with the Peninsula of Kamchatka, in Asia, opposite thereto, and Islands, dispersed over the Pacific Ocean, to the north of the line.

Sheet IV: Chart of the Atlantic Ocean, with the British, French & Spanish Settlements in North America and the West Indies.

Sheet V: Chart containing the greater part of the South Sea to the South of the Line, with the Islands dispersed thro’ the same.

Sheet VI: Chart of South America, comprehending the West Indies, with the adjacent Islands, in the Southern Ocean, and South Sea.

Cartographer(s):

Braddock Mead a.k.a. John Green (c. 1688 – 1757) was undoubtedly one of the most fascinating and important cartographers in the history of the London map trade. Born in Ireland, Mead showed an interest in cartography from an early age, publishing his first volume, The construction of maps and globes, in 1717. Despite his talents and ambitions, Mead tended to get himself in trouble and his petty crimes and poor reputation soon forced him out of Dublin. He moved to London and changed his name around 1717, but his Bohemian lifestyle of gambling and petty crime continued. In 1728 he was imprisoned for his role in a plot to defraud Bridget Reading, a 12-year-old Irish heiress; the main ringleader of the plot was hanged.

When Mead was released from prison, he took the alias of John Green and began a noteworthy career in mapmaking. His maps were characterized by an almost scientific approach to the compilation of geographic information and a meticulousness that outshone his contemporaries. Thomas Jefferys, the illustrious geographer to the Prince of Wales (later King George III) recognized his talent and hired him as an assistant in 1750. During this period he produced a number of groundbreaking new maps, focusing in particular on the American continents and Arctic regions. Mead compiled many of Jefferys’ finest and most celebrated charts, producing his hemispherical map within the first years of his employment. Mead’s life came to a tragic end when he committed suicide by jumping out of a window in 1757.

Braddock Mead is widely acknowledged for new standards in cartography. In the book British Maps of Colonial America, a standard reference on the early cartography of New England, William P Cumming writes: “The genius behind Jefferys in his shop was a brilliant man who at this time went by the alias of John Green…. Green had a number of marked characteristics as a cartographer. One was his ability to collect, to analyze the value of, and to use a wide variety of sources; these he acknowledged scrupulously on the maps he designed…. Another outstanding characteristic was his intelligent compilation and careful evaluation of reports on latitudes and longitudes used in the construction of his maps…” (1974: 45). Another great scholar of early American cartography, G.R. Crone, thought that Green: “deserves to be remembered for breaking away from the old unreformed cartography, and for perceiving clearly, and following as far as the existing data permitted, the methods upon which modern cartography was to be established” (1949:88).

James Gordon BennettJames Gordon Bennett (1795–1872) was the founder, editor, and publisher of The New York Herald and a major figure in the history of American newspapers.

Robert SayerRobert Sayer (1725–1794) was a leading publisher and seller of prints, maps, and maritime charts in Georgian Britain. He was based near Fleet Street in London. This was a business he had taken over from his brother in 1748 after he had won it by marrying the widowed daughter-in-law of another famous London map seller, John Overton.

After taking on his servant John Bennett as an apprentice in 1765, and later partnering up with him, the firm of Sayer and Bennett became one of the most important map houses of late 18th century Britain. From then on, the Sayer & Bennett firm was particularly well-known for their maps and atlases focusing on the Americas during a time of great upheaval and change (i.e. the French and Indian War, and especially the American Revolution).

In the beginning, many of these publications would have an obvious British slant, but as things progressed, Sayer increasingly realized the potential in creating reliable maps of an independent North America. Consequently, Sayer & Bennett produced some of the most significant charts and atlases of the British colonial possessions in America and later of the early United States.

Condition Description

An extraordinarily clean copy backed on new linen.

Watermark: each sheet with a fleur-de-lis within a shield with a crown above and below LVG and countermark IV or VI.

References

G. R. Crone

1949 John Green. Notes of a Neglected Eighteenth Century Geographer. Imago Mundi 6: 85-91

1951 Further Notes on Bradock Mead, alias John Green, an eighteenth century cartographer. Imago Mundi 8: 69-70 .

1951 John Green, Remarks, in support of the New chart of North and South America; in Six Sheets (London: Thomas Jeffreys, 1753).