A rare and early tourism pamphlet promoting Aleppo under the French Mandate.

[ALEPPO] Toi qui te plains de l’infortune, Lève-toi et va vers… ALEP… Comme le malade épuisé. Soupire après la guérison.

$375

In stock

Description

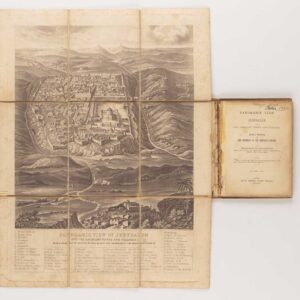

A piece of locally-produced ephemera showing the now-destroyed citadel of Aleppo.

This is a rare Franco-Syrian promotional pamphlet designed to encourage French tourists to visit Aleppo in northern Syria. This little booklet presents the city’s many great attributes, shows images of its most ancient and celebrated features, and provides all the logistical information needed to travel from France to Aleppo as an early tourist. In addition to expounding the city’s many attractions, the booklet also describes a number of rural sites and places worth visiting on day trips from Aleppo. These include the Dead Cities of the Syrian steppe, the Basilica of Simon the Stylite, the ancient Roman-Byzantine capital of Antioch (modern Antakya in Turkey), the intact Roman city of Apamea, or the gorgeous old city of Hama on the Orontes River, adorned with its enormous wooden watermills (noria).

The title is a playful take on an old Arab proverb: Toi qui te plains de l’infortune, Lève-toi et va vers… ALEP… Comme le malade épuisé. Soupire après la guérison (You who complain of misfortune, Get up and go towards… ALEPPO… Like the exhausted patient. Sigh after healing).

Inside the booklet, the subject matter is essentially divided into four sections: 1). An introduction to the city and its sites (visitez Alep); 2). How to get there from Europe (Vers Alep); 3). What to experience once there? (A Alep…); and finally, 4.) Where to go and what to see using Aleppo as a base (D’Alep…). Each section is illustrated with detailed vignettes of some of the places and scenes discussed in the texts. In the centerfold, we find a gorgeous double-page view of Aleppo Citadel – the city’s iconic Ayyubid fortification. Built on a spot elevated by millennia of occupation, the old city of Aleppo lies sprawled out beneath its monumental towers and bridge.

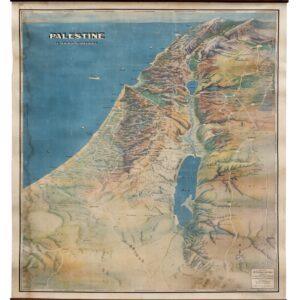

On the back cover, we find a small map showing readers the different possible routes when traveling from Paris to Aleppo. These are further expounded in the text inside. From the map, it is clear how Aleppo was conceptualized within a late Victorian framework of travel to the Middle East, often labeled The Orient Express. While travel onwards to Damascus was possible, in the 1920s, the ‘Orient Express route’ culminated in Aleppo.

While the booklet is undated, several indicators confirm it belongs to the early part of the French Mandate period in Syria (1920-1946). This is, for one, reflected in the division of Syria into a northern state with Aleppo as its capital and a southern state with Damascus as its capital. This division was instigated in 1920 and formalized in early 1923. The lack of photographs in the booklet and the consistent labeling of addresses and place names in French further suggest its dating to the early Mandate period. Finally, we note that the people involved in the booklet’s creation were two Frenchmen and an Armenian (there has been a substantial Armenian community in Aleppo for centuries), no native Syrians.

With more than 6000 years of continuous occupation, Aleppo is one of the oldest functioning cities on the planet. It has been a cosmopolitan hub of trade and culture for the entire region for centuries. With Syria’s descent into Civil War in 2011, Aleppo became a contentious hotspot of resistance, with multiple ethnic and religious groups challenging the Assad regime. Consequently, war raged within the city for months, causing immeasurable destruction to some of the world’s finest and most ancient cultural heritage. The 13th-century Citadel was used to store weapons and shield resistance fighters, attracting massive shelling and causing irreparable damage to the ancient fortifications. Large swathes of the old city were also laid to waste. While some of this has been rebuilt, the damage to the original architecture and infrastructure has meant a permanent change in the city’s appearance.

Context is Everything

Tourist publications produced under the French Mandate in Syria are generally scarce, with this example of local advertising being unrecorded. While Syria had a lot to offer, understanding the semi-colonial dynamic at play here requires insight into the history of France’s mandate to govern here. Understanding the significance of Mandate Period publications in terms of historical documentation is also closely associated with the Syrian Civil War’s profound societal and material consequences. Both of these phenomena will, therefore, be dealt with briefly below.

Syria as a French Mandate (1920-1946)

The French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon emerged as a League of Nations mandate following World War I, following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Initiated in 1920 and formally established in 1923, the commission aimed to oversee Syrian territories until they were deemed ready for self-governance and to transition into sovereign states. France was granted the mandate for Syria, encompassing modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Alexandretta (and thus the ancient city of Antioch). The intention of the mandate was to function differently from traditional colonialism, with France acting more as a trustee for the inhabitants until their autonomy could be guaranteed.

French control was formalized through various administrations, including the Syrian Federation, the State of Syria, the Mandatory Syrian Republic, and smaller states like Greater Lebanon, the Alawite State, and the Jabal Druze State. However, the French Mandate was marked by resistance and dissent, with revolts and uprisings across all these Syrian states, leading to three years of French consolidation from 1920 to 1923. The French sought to divide ethnic and religious groups in the region to extend their rule. This included suppressing the power and influence of local authorities and maintaining dominance through the mandate administration.

In the aftermath of World War I, the French faced opposition as they imposed the mandate, as the Syrians aspired for independence and unity under the leadership of Faisal, son of Hussein bin Ali, King of Hejaz. Despite local resistance and uprisings in different states, the French maintained strict control of the Syrian territories, (mis)shaping the political landscape through ethnic and religious divisions and introducing governance practices to hinder the local development of independent and reliable governing bodies.

The Syrian Civil War (2011-present)

The Syrian Civil War erupted in March 2011 amidst widespread discontent with Bashar al-Assad’s government. The discontent sparked protests and pro-democracy movements across Syria, coinciding with a broader regional trend known as the Arab Spring. The initially peaceful demonstrations were met with violent suppression by Assad’s security forces, escalating the situation into an armed insurgency by 2012. Rebel groups like the Free Syrian Army emerged, challenging Assad’s rule, leading to a multifaceted conflict involving various factions and external powers.

The conflict’s dynamics were complex, with the Syrian Arab Armed Forces, supported by Iran and Russia, representing Assad’s government. In contrast, opposition groups, including the Syrian National Army and Free Syrian militias, formed the Syrian Interim Government. The rise of the Islamic State terror group added further complexity. Seizing control of territories in Eastern Syria and Western Iraq and implementing horrific practices of religious violence, ISIS prompted a U.S.-led coalition intervention as well as military support for the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Later, Turkey also intervened, targeting both IS and Kurdish forces while backing the Syrian National Army.

The war reached its peak from 2012 to 2017 but persisted as a crisis, leading to over 470,000 to 610,000 estimated deaths and a significant refugee crisis. By 2020, Assad’s government controlled the majority of Syria, with sporadic fighting continuing in some regions. By 2023, the conflict had settled into a low-level stalemate, with Assad’s regime largely secure, ongoing economic challenges, and attempts at peace talks proving fruitless. The Syrian people endured immense suffering, with millions displaced and humanitarian conditions remaining dire despite sporadic confrontations.

Census

Having been produced for consumption purposes, only a few of these early tourism publications have survived, making them both rare and highly collectible. Unsurprisingly, we have been unable to identify a single other example of this particular booklet in any private or institutional collection, nor indeed on any antiquarian platform. It is an ephemeral item of great rarity. The OCLC has no listings of this booklet, and even an image search using all of the images of the booklet has yielded no results.

The booklet was compiled and published by Northern Syria’s Tourist Office with the assistance of the new National Museum of Aleppo. George de Rotor wrote the texts, and G.L. Martin and Léon Kéhéayan designed the layout and illustrations. It was printed by the Imprimerie ROTOS on Place Gouraud in Aleppo itself. While we have been unable to identify any other examples of this booklet, we have established that its design is linked to Charles Godard’s (1899-1978) Alep, essai de géographie urbaine et d’économie politique et sociale from 1938. This book used the same fonts for the title page as our booklet and was printed with the same French Aleppo-based printer. Based on its content and the history of the French Mandate in Syria, we nevertheless hold that the booklet predates Godard’s far more comprehensive work. For Godard’s book see: https://www.bibliotheque-eglise-armenienne.fr/collections/a-la-une-ce-mois-ci?start=4

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Very good.

References