Currier & Ives 1871 Great Chicago Fire.

The Great Fire at Chicago. Octr. 8th 1871.

$9,500

1 in stock

Description

The tragedy that created modern Chicago.

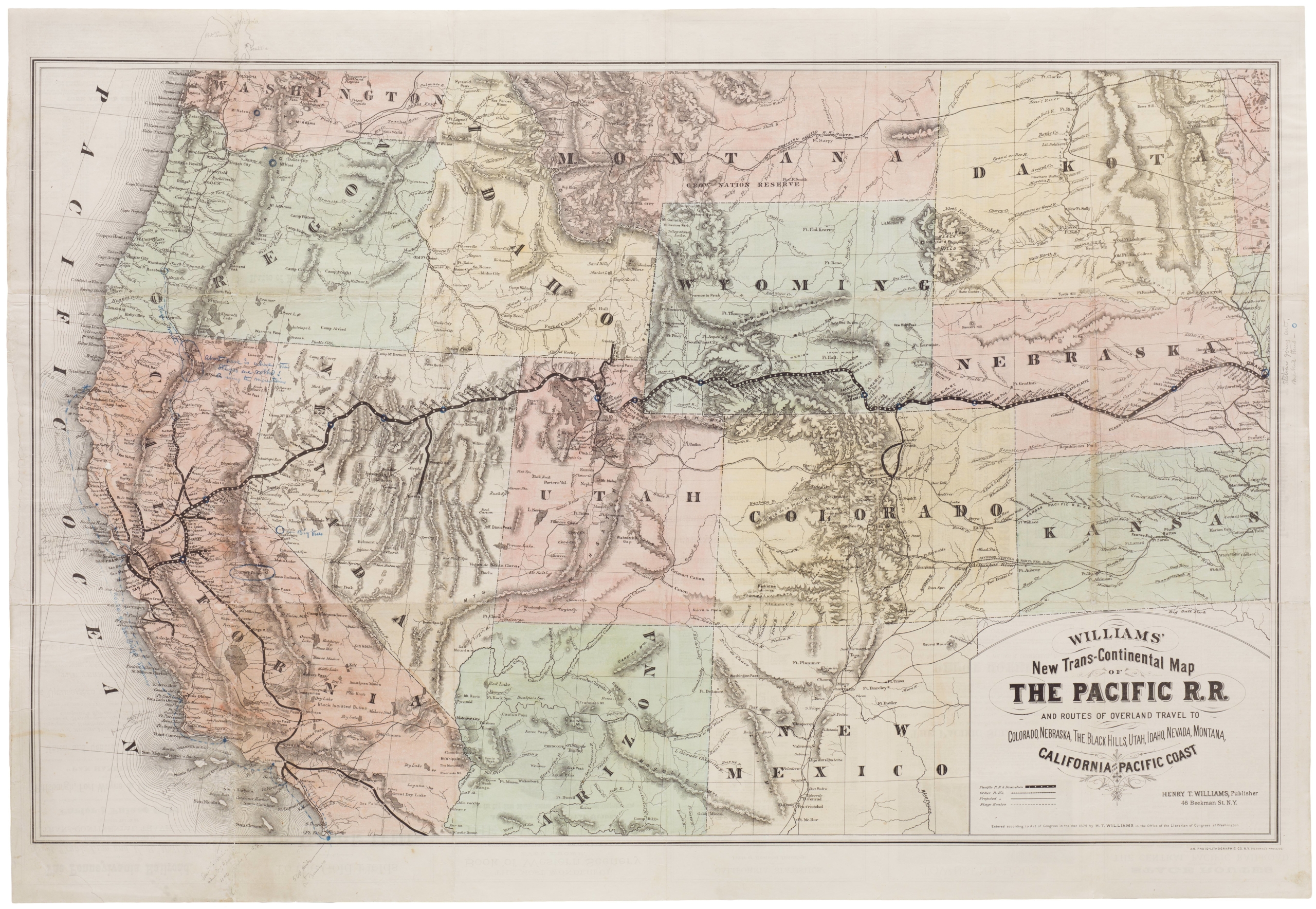

A dramatic Currier & Ives hand-colored lithograph depicting Chicago during the Great Fire of 1871, which destroyed much of the city.

The lithograph provides a spectacular view of the burning city as seen from Lake Michigan, with the mouth of the Chicago River at center. We see countless people scrambling for safety along the entire waterfront, underlining the extent of the human catastrophe. The calamity was so great that it changed the face of Chicago, which is why even those familiar with the city today will have a hard time recognizing many of the features that Currier & Ives included in their dazzling rendition.

Immediately to the right of the river, we see a tall lighthouse on what was then known as Light House Pier. This was demolished as part of the city’s post-fire refurbishment and was replaced in 1916 by the famous Navy Pier as part of Daniel Burnham’s master plan for Chicago. Beyond the section of the lakefront dominated by Navy Pier, we find integral parts of the city’s original infrastructure, including the water- and gasworks. While the fierce conflagration has reached all the way to the waterfront in this part of the city, we note the presence of a small beach in the northernmost part of the image. This must constitute either Ohio Street Beach or Oak Street Beach, beyond which we already find the iconic Lake Shore Drive.

Looking up river, we note the presence of several bridges. In the late 19th century, Chicago featured four bridges across the river. The most proximate to our vantage point and the oldest and most famous is the Rush Street Bridge, which was Chicago’s first modern bridge. It was finished in 1857 and was constructed as a swing bridge that could pivot on a central pier in the river to allow taller ships to pass.

On the south or left side of the river, we see Chicago’s large and famous train Station, known as the Great Central Passenger Depot, at the end of what today is Printer’s Row. Adjoining the depot out towards the river were two mammoth elevators that were considered technological marvels of the age. We find other iconic buildings from Chicago’s early days along the waterfront, including the central Court House and Michigan Avenue Hotel. The lake is crammed with vessels, presumably either escaping the fire or engaging in that very human trait of catastrophe voyeurism. One ship at far right has itself caught fire.

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871

The Great Fire of 1871 was one of the most significant events in Chicago’s history. The fire is often blamed on Mrs. O’Leary’s cow knocking over a lantern. Still, historians generally discount this explanation and agree with the earliest reports by the city itself that the cause for the start of the fire could not be determined. Regardless, the ultimate cause of the fire was arid weather combined with the use of wood as the city’s overwhelming material for building construction, along with the ready supply of other flammable materials like hay and tar (including on the roofs of wooden buildings).

The dry and windy conditions carried the fire quickly through the city on the night of October 8. Beginning in the southwestern part of the city, the wind carried the fire quickly towards the northeast, straight into the densest part of the city. More than 3 square miles of the city were destroyed, some 300 people were killed (initial reports maintained a higher figure), and 100,000 were left homeless.

In the aftermath of the fire, General Philp Sheridan, of Civil War fame, was tasked with maintaining order in the city, which helped to organize early relief and reconstruction efforts. The city was rebuilt along the lines that would carry it into the 20th century and beyond; the fire effectively led to the birth of modern Chicago. Afterward, Chicago and other cities refocused efforts on preventing and fighting fires with basic building codes and professional fire departments. Chicago’s reconstruction was crowned with hosting the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Census

This view was published by Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives in New York in 1871. It is rare, being held only by the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Museum of American History (Smithsonian).

A similar example sold at Christie’s for $11,250 in December 2016 (Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts, including Americana).

Cartographer(s):

Currier and Ives was a highly successful American printmaking firm that operated from 1834 to 1907. The company was named after its founders, Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives. They specialized in producing lithographic prints that depicted a wide range of subjects, including landscapes, historical events, portraits, and genre scenes.

Nathaniel Currier, born in 1813, started his career as a lithographer in the 1830s, creating images of current events and scenes of everyday life. He formed a partnership with James Merritt Ives, a bookkeeper, in 1857. Ives had a keen business sense and contributed greatly to the success of the firm. Together, they established Currier & Ives, with Currier as the primary artist and Ives managing the business operations.

Currier & Ives became renowned for their high-quality lithographs, which were affordable and accessible to a wide audience. The company employed a team of talented artists who produced the original artwork, which was then transferred onto lithographic stones for mass production.

Condition Description

Slightly uneven toning in margin from previous framing. Deckled edges.

References