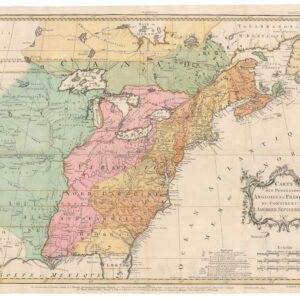

A beautiful hand-colored example of Coronelli’s ground-breaking 1688 map of North America.

AMERICA SETTENTRIONALE Colle Nuove Scoperte fin all’Anno 1688…

Out of stock

Description

Key points:

1. Vincenzo Maria Coronelli’s “America Settentrionale” is one of the essential early renditions of North America and a cornerstone in any serious map collection focusing on America.

2. Coronelli’s official positions in Venice and at the French royal court in Paris afforded him unique access to reports and manuscript materials.

3. The map features one of the first mentions of the name ‘Chicago’ on a printed map, copious notes of discovery, information on Native American settlements, and more.

4. Attractive Venetian Baroque embellishments, including a superb allegorical title cartouche, complement the geography.

Details

This splendid example of Vincenzo Maria Coronelli’s important double-page map of North America is a testament to a cartographer at the zenith of his prowess. Published in 1688 in Coronelli’s hometown of Venice, this was one of the first highly detailed charts of the American continent to appear on the open market and is, in the typical style of the Venetian Baroque, elaborately embellished on all fronts, including a fantastic title cartouche imbued with symbolism. The map was well-informed and executed with enormous skill, and it soon became an essential reference for other cartographers working in North America in the late 17th century.

Among the map’s many landmark features, we might note its very comprehensive toponymic record, highly detailed and accurate physiography, extensive and detailed annotations—especially regarding frontier territories—and exquisite artwork, both in regard to the three cartouches and the rendition of the landscape itself. It is, by all measures, a beautiful creation, splendidly preserved and eminently presentable.

Coronelli’s sources

Being the official cosmographer of Venice’s commercial hub undoubtedly helped Coronelli track down reliable sources and acquire the most recent and exciting information. However, this map shows that his position as a royal cartographer in the French court afforded him a real advantage. Observations and data gathered by French officers, merchants, and fur traders were reported back to Paris and thus became available to Coronelli, supplying him with pertinent information. This map is no exception, and we will find inclusions that ultimately refer back to very recent French discoveries in America (e.g., those of Sieur de La Salle and Father Louis Hennepin, both discussed below).

Spanish informants appear to have been a critical source in compiling this map, though many also came to Cornelli through the French court. In particular, a manuscript and map from the hand of Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa proved informative. Peñalosa had been the Spanish governor of New Mexico between 1661 and 1664. He spent the following years meticulously preparing descriptions and a map of the region, which he presented to the French King in 1687. He hoped that the French would invade Mexico from neighboring Louisiana and that he might be reinstated.

The Bibliotheque du Depot de la Marine retains a manuscript map of the southwest based on the reports of Peñalosa. These are likely the documents to which Coronelli refers in the Avertissement of his map of the American Southwest, Le Nouveau Mexique appele aussi nouvelle Grenade et Marata, avec partie de Californie, published in Paris with Jean-Baptiste Nolin in 1687. Together with our 1688 chart, the two maps testify to the swiftness Coronelli received and incorporated intelligence briefs onto his maps.

The information and toponyms presented on the Coronelli/Nolin map of 1687 and our map marked an essential development in the mapping of Upper Mexico and the American West. They were just the second and third maps to depict the Rio del Norte flowing towards the Gulf of Mexico, the first being a relatively obscure work by Giovanni Battista Nicolosi, published in Rome in 1660. Earlier maps of the region, for example, Hendrik Hondius and Jan Janszoon’s America Septentrionalis (1647) or Nicolas Sanson’s Amerique Septentrionale (1651), erroneously depict the Rio del Norte as extending from Santa Fe southwest into the Gulf of California. While Nicolosi came first, Coronelli’s map of North America, which was widely admired and copied, established the new configuration. Furthermore, Coronelli is more explicit in demonstrating the cartographic correction, including a short note underlining the misconception: “The Rio del Nort flows into the Gulf of Mexico, not the Sea of California.”

The river that flows from the area around Santa Fe to the Gulf of Mexico is today known as the Rio Grande in the United States and the Río Bravo del Norte (or simply Río Bravo) in Mexico. Nicolosi does not include either of these names, placing a small toponym, ‘Rio Escondido,’ along the river near the Gulf. Coronelli is more thorough. Having, in effect, “swung” the Rio del Norte to the east, away from the Gulf of California and towards the Gulf of Mexico, he retains the name. But to reconcile this new model with the existence of rivers at the Gulf of Mexico already found on earlier maps, for example, the Rio Madalena – seen on both the Hodius and Sanson maps mentioned above – Coronelli subdivides the river into a northern and southern section.

The two sections together roughly follow the course of the Rio Grande as we know it today, from Santa Fe to southwest Texas and finally to its estuary at the Gulf of Mexico. As mentioned, the upper river is labeled Rio del Norte. For its part, the lower river is called ‘Rio Bravo,‘ As far as we know, the 1687 and our 1688 charts are the first printed maps to use this name, which we assume was taken directly from Peñalosa’s report.

Peñalosa’s report also contained information on settlements, forts, roads, and other essential features in the landscape, most of which Coronelli incorporated into his map on various levels. This is evident, for example, along the Rio del Norte valley, which is south of Santa Fe, has been provided with a wealth of new information on the latest settlements.

Among the many other interesting geographical features, we find the depiction of the Mississippi River, including the tributaries that sustain it. However, the river’s mouth has been placed much too far west, most likely due to the fresh reports of French explorer and fur trader Sieur de la Salle. La Salle launched a canoe expedition in December of 1681, descending with fifty-four Indians and compatriots from the mouth of the Illinois River to the Gulf of Mexico. Understanding the importance of his voyage’s purpose and potential outcome, La Salle carefully plotted the river valley and reported his findings in France. Before returning upriver, La Salle named the lower river valley ‘Louisiana’ in honor of his king, Louis XIV.

What happened next is a point of contention among historians of this period. On his charts, La Salle positioned the Mississippi Delta about 400 miles too far to the west. Whether he did so because of faulty equipment (supposedly his compass was broken and his astrolabe was defective) or because he knew that the crown was more likely to support a new expedition near known silver mines in Spanish territory is inconclusive. In any event, La Salle created a new cartographic myth that Coronelli unknowingly promulgated.

Yet many aspects of Coronelli’s rendition of the Mississippi were entirely new and amazingly accurate, considering the era and the type of informants he was dealing with. In particular, the tributary system is interesting because it hints at some form of connectivity between the riverine systems and the Great Lakes – all included on the map. The uppermost part of the Illinois River, which is labeled ‘Chekagou R.,’ leads up to a portage point with the same name and only a short distance from the shores of Lake Michigan. This modest toponym carries excellent significance: a few centuries later, this portage site had become Chicago, America’s great entrepreneurial hub and one of the cities that helped propel the United States into the modern age. Here is one of the first times that ‘Chicago’ appears on a printed map; it is also found on Coronelli’s map of New France, published in Paris one year prior in 1687.

Coronelli’s political agency

Maps like this were functional geographic tools and vehicles of propaganda, political boundaries, and territorial justification. This is seen in delineating territories and consistently including information on who discovered what areas and when. In some cases, these are sweeping attributions, such as in inland California, labeled ‘Scoperta da Spagnioli L’anno 1598’ (discovered by the Spaniards in 1598). In other cases, mentions are far more specific, such as in the annotations regarding Sieur de la Salle’s journey.

Coronelli’s map depicts the latest political subdivisions of the continent by demarcating the most up-to-date territorial borders. In the late 17th century, much of America was still controlled by the great colonial powers of the age: Holland, Spain, France, and England. However, other nations attempted to join the fray, such as Denmark and Sweden. Coronelli alludes to the former on his map in the waters of Hudson Bay, where a relatively large inscription reads ‘Scoperto dagli Danesi’ (discovered by the Danes).

This uncommon reference pertains to a little-known but extremely impressive journey led by the Danish-Norwegian explorer Jens Munk. In 1619, Danish King Christian IV charged Munk with discovering the Northwest Passage. The goal was to secure a new and quicker route to India on behalf of the Danish Crown and colonize the route with the intention of collecting taxes.

Over the coming decades, Denmark lost most of its impressive navy and status as a European powerhouse. Jens Munk’s mission was unsuccessful, but the journey is one of the most extraordinary tales of Polar exploration and survival. The expedition made it into Hudson Bay in the autumn of 1619 and set up camp for winter near the mouth of the Churchill River. When spring came, only Captain Munk and his cabin boy were still alive, the rest having succumbed to scurvy and starvation. Suffering from extreme exhaustion, hunger, and vitamin-c deficiency, Munk spent what he believed to be the last hours of his life in his cabin, writing his testimony of events in a shaky hand if their bodies were one day found.

In the end, Munk survived, and his letter still exists in the archives of the Royal Danish Library. He managed to rig a small yacht with the help of his cabin boy, and together, they crossed the Atlantic in early spring. Upon his return to Bergen (then Danish), Munk was imprisoned for wasting the King’s resources. Still, when King Christian heard of his unlikely return, he immediately secured his release and brought him to Copenhagen. Munk’s records formed the basis for a royal commission investigating the possibility of establishing a formal Danish colony on Hudson Bay. However, the notion was soon abandoned due to the eruption of war across Europe – a war in which Denmark did not fare well. Only after the cessation of the Thirty-Year War (1618-48) did the British and French realize this region’s value and begin making their first claims.

A remnant of another failed Scandinavian attempt to establish a foothold in North America is found on an elongated isthmus just south of New York and extending into the Sea of Virginia, which Coronelli has labeled ‘Nuova Suecia,’ or New Sweden. The 17th century was the heyday of Sweden’s military and naval prowess. Between 1638 and 1655, the Swedish King entertained ideas of a formal Swedish colony on the lower reaches of the Delaware River.

Despite these lofty ambitions, the colony was not long-lived. The Swedes could not sustain a satellite that far away – especially after engaging heavily in the second Great Nordic War (1655-1661) – so the area was ceded to the Dutch, who quickly incorporated it into their crown colony of New Holland. Even though he included New Sweden – perhaps as a curiosity – Coronelli omitted the Dutch colony from his chart, presumably because the English had already subjugated it at the time of the map’s publication.

Coronelli’s sense of drama and aesthetics

Several important topographical features on the map are worth highlighting. Along the upper reaches of the Mississippi River, we find three clusters of mountains depicted along the west bank. These are manifestations of rumors of a vast mountain range to the west and constitute an early attempt to depict the Rocky Mountains. In the east, we find a rendition of the somewhat more known but still wild Appalachian Mountains, to the south of which we find Lake May. This is the same lake that H. Hondius identified as a sweet water lake associated with the River de May. Scholarly consensus has yet to be reached on the attribution of the River de May, with some identifying it as St. John’s River and others as St. Mary’s River; in the latter case, the large lake would represent Okefenokee Swamp.

Throughout the map, open or uncharted spaces are filled with evocative illustrations of Native peoples engaged in warfare, fishing, hunting, and food preparation. Many, if not most, of these images constitute reflections of the European imagination of indigenous peoples and should not be taken at face value. That said, some rather disturbing scenes are included. The most well-known is on the southwest banks of the Hudson Bay, where a smoke chamber has been constructed – presumably for curing meats. Outside, two men are roasting a human leg over the fire, while a third seems to be eating another human limb. In addition to this rendition of cannibalism – the worst sin imaginable for a righteous European Christian – we find another slightly more humorous but equally dismal scene. Just south of the Chekagou River, a poor soul seems to have been gobbled up by a crocodile, to the apparent anguish of his companions. The story does not, however, appear to have ended well for the crocodile: another image just below the devouring scene shows the crocodile wrapped in a net and being prepared for consumption.

The representative imagery also includes several elaborate Native American settlements, including a circular village with a palisade wall just east of the Mississippi, an Algonquin village in the woods just north of Lake Ontario (seemingly with a gentleman relaxing in a hammock strung up between two trees), and a somewhat mysterious ‘township’ located between the uppermost tributaries of the Mississippi. The latter has a large central building surrounded by four lofty towers and several smaller dwellings. The site is labeled “Issatis Populi che fanno 24 villagi” in reference to what must be a conglomeration of villages belonging to the Issati tribe of North Dakota (related to the modern Mdewakanton). This information most likely came from the descriptions of the French missionary Father Louis Hennepin, who, after a journey to the region in 1680, described the Issati and reported that there are many villages in the neighborhood of Mille Lacs Lake in what is today northern Minnesota. The annotations generally focus on the regional divisions of tribes with extensive labeling of tribes or unions throughout the map.

The symbolism and excellence of the title cartouche

In the map’s upper left corner, we find its elaborate titular vignette. The text is framed by elaborate and profoundly symbolic imagery engraved in a sumptuous Venetian Baroque style. The title is seated on a triangular stone slab crowned by a wreathed heraldic shield and draped by two figures: an angel on the right and a Valkyrie on the left. While we have yet to identify the exact origin of the heraldry on the shield, the flat hat with long tassels above the shield is undoubtedly a symbolic reference to the Archdiocese of Bologna. This is verified by the text itself, which, in addition to identifying the cartographer and cementing his position as cosmographer of Venice, includes a dedication to Monsignor Felic Antonio Marsily, the Archdeacon of the Cathedral of Bologna.

To the left of the title, we find four mysterious figures, two males and two females. These have often been interpreted as gods blessing the European discoveries in the New World. One of the male figures is an angel, while the other sits, draped in cloth, holding what is presumably an albatross. The angel seems interested in getting his hands on this bird, but whether this is an act of assistance or contention is unclear. Between the two men, a scythe and an hourglass lay on the ground: easily understandable references to human mortality. At the seated man’s feet, we see a reclining female figure nude with incredibly long flowing hair that reaches all around the group. She gazes longingly up towards the second female figure, handing her a sun-dial compass. In her other hand, she holds a printed map, and at her head is a magnetic compass alongside the bow of a sinking galleon.

All of these objects and the oceanic appearance of her flowing hair suggest that this represents her tremendous and noble drive to explore the world. Looming largely above this maritime nymph, we see the strangest figure of them all. Caped but otherwise nude, the persona’s head is almost entirely enveloped in a radiant solar headdress, reminiscent of Aztec garbs and clearly representative of the indigenous cultures of America. While a matter of interpretation, one might venture that handing the sundial compass represents the superior scientific and technological knowledge that Europeans brought to the Americas. In contrast, both the death symbolism of the scythe and the hourglass and the rather explicit danger of going down with one’s ship represent the many perils facing those who dare venture into this new world.

A second large cartouche, found in the lower right of the map, depicts a sheet or canvas tied between two outstretched oak branches rising from the water and decorated with ribbons. On the canvas are six scale bars showing Italian miles, French leagues, Spanish leagues, German leagues, nautical leagues, and ‘leagues of an hour of walking’ respectively.

Coronelli’s Island of California

While incredibly detailed and impressively accurate for the time, the map also clearly includes a number of regions in America that remain entirely unexplored, the Great Plains and Northwest Pacific being the most obvious. Other more well-known and settled areas, such as the Caribbean or East Coast, have been rendered in much greater detail and focused on colonial delineation.

And, of course, situated prominently on the left side of the map, we see the greatest of all cartographic myths: the representation of California as an island. This cartographic enigma, celebrated by many collectors, first occurred on a printed map by Diego Gutiérrez in 1562. The idea developed following early Spanish expeditions up the Pacific coast. In particular, the writings of a Carmelite friar, Antonio de la Ascension, seem to have promulgated the impression among Spanish mariners and cartographers, and from here, it soon spread to the former Spanish domain of the Netherlands and the rest of Europe.

Before long, California began to appear in different shapes and sizes. By the 1620s, the concept had become widespread, with cartographers such as Henry Briggs (1625), John Speed (1626), Nicolas Sanson (1636), and Henricus Hondius (1650) all incorporating the concept into their maps so that by the time Coronelli compiled this chart in the late 1680s, the notion had become solidly lodged in the geographical awareness of most Europeans. The idea was so tenacious that even though Father Kino formally rejected it based on personal observation and verification (published in Paris, 1705), it continued to find its way into many maps well into the 18th century.

Coronelli’s map depicts the island with an enlarged upper half and two deep bays extending into the island from the north. This is the so-called ‘Second Sanson’ or ‘Luke Foxe’ model, based on Nicolas Sanson’s second rendition of the continent in 1657. Earlier versions depicted California more diminutively and with a flat top without any bays or inlets. Another visible and labeled feature on the map is a small promontory extending out into the Pacific just north of California and labeled Agubela de Gato. This was initially identified by the English explorer Luke Foxe (1586-1635) during an extensive journey to the Northwest Pacific (it is unclear whether he sailed as far south as California).

Coronelli is fully aware of how tentative his understanding of America’s Pacific geography is. As if to make clear his considerations in compiling this map, a small explanatory text has been inserted in a simple yet beautiful little cartouche consisting of a flowering laurel wreath in the South Pacific. This provides a brief history of exploration of the Sea of Cortes, pointing to several critical Spanish voyages in the first half of the 16th century.

Oddly enough, if we forget that the Sea of Cortes is drawn as a straight instead of a closed gulf, there is a wealth of detail on California’s many waterways and where they empty into the bay. The sea is identified as the Red Sea of Cortés – called ‘Mer Rouge’ by the French – referring to the iron-rich riverine discharge, which could turn the bay a brownish red in spring. The focus on rivers was crucial for various reasons, including survival, navigation, and infrastructure. Regarding survival, the procurement of fresh water was always on the mind of any experienced captain. But rivers were also crucial from a navigation perspective. They constitute recognizable features along an otherwise unknown coastline and sometimes link to riverine systems observed inland. Finally, rivers constituted potential transport and trade corridors, in some cases allowing maritime vessels to penetrate significantly inland to explore mercantile opportunities.

Context is everything

This map was produced in an age where the excitement about America’s possibilities had never been more pronounced. Coronelli, who in his lifetime achieved great fame and recognition as a map- and globe-maker, had access to many French, Spanish, and Italian sources and was skilled at combing through them for the most relevant new content. In this light, producing a full chart of North America was not only something that enhanced his position and wealth further, but it was also a statement piece, an opportunity to show off one’s skills and sources and stand out from the crowd.

Coronelli produced maps of American regions, including Western Canada, the Great Lakes, and Mexico. This particular map, however, was issued as part of his celebrated Atlante Veneto atlas, a thirteen-volume folio-sized atlas published in Venice between 1690 and 1701. The atlas covered the Old and New Worlds, Polar Regions, ancient and contemporary cartography, and geographers and included astronomical and historical data to complement and contextualize the maps. It was a true post-Renaissance masterpiece, intended to follow Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior (1662). The impressive folio size allowed Coronelli to design and print his maps as larger sheets. In some cases, such as this one, the most attention-grabbing maps were published across two full sheets, allowing for the incredible detail on this chart.

Cartographer(s):

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli (1650 – 1718) was a Franciscan printer, cartographer, and globe-maker from Venice. Due to his religious background, many of his charts have been signed P. Coronelli, meaning Père or ‘Father’, and referring to his status as a friar of the Franciscan Order. He was appointed official cosmographer for the city of Venice and was later employed as royal cartographer to the King of France. In particular the latter position meant that he had access to the latest records and materials from French pioneers and voyages of exploration. This caused many of his charts to be cutting-edge innovations that redefined the newly discovered parts of the world in an entirely novel fashion. It also meant that Coronelli would have no scruples in declaring uncontested or virgin land in the New World as part of Nouvelle France. This is exemplified in Coronelli’s celebrated 1685 chart of Western Canada or Nouvelle France, in which the official French territories have been expanded thousands of miles to the west and south, so that most of the Midwest, including the Mississippi Valley, has been subsumed under a French claim.

Coronelli’s access to the latest French sources and intelligence is part of what has made his maps so cartographically decisive and collectible. An example of this is found in his 1688 chart of upper Mexico and the Rio Grande (modern Arizona, California, and parts of New Mexico). This map was, at the time of its publication, one of the most detailed and accurate maps of the Rio Grande on the market. The detailed information conveyed in Coronelli’s map came directly from Diego Penalosa, the Spanish governor of New Mexico (1661-63) who turned rogue and provided the French King with a wealth of strategic geographical information. His ambition was to lure the French into attacking New Mexico from the neighboring territory of Louisiana. Despite the controversial source of his information (or perhaps precisely because of it), Coronelli does not hesitate to lay credit where credit is due, and mentions Penalosa directly in the map’s cartouche.

Condition Description

Two sheets, joined. Slight toning on left sheet.

References