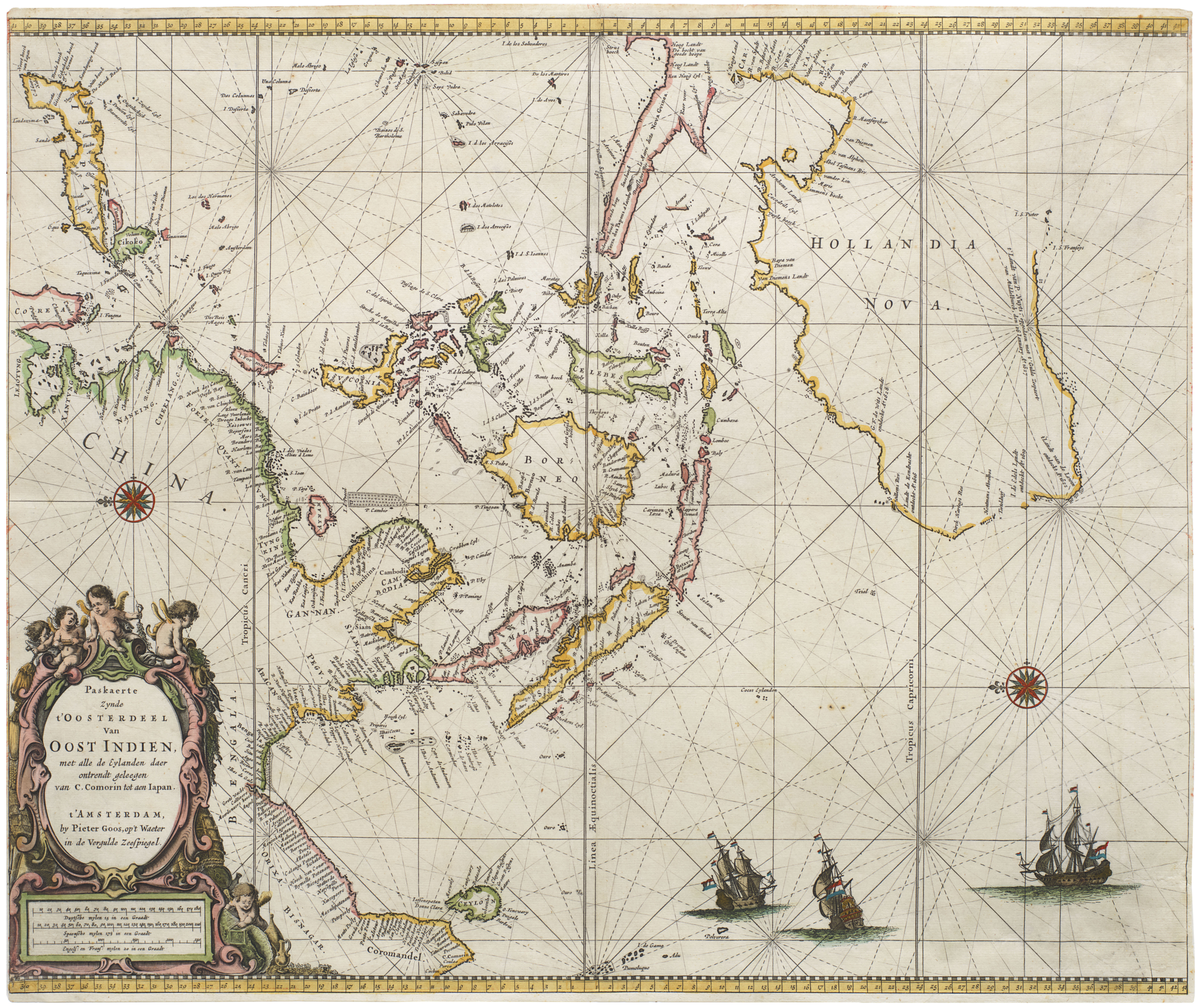

The first Spanish Map of the Philippines and Spice Islands.

Descripcion De Las Indias Del Poniente.

$6,500

1 in stock

Description

The first printed map of Southeast Asia to explicitly delineate the Line of Demarcation defined in the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529).

An early example of persuasive cartography, shifting the division of the world dramatically in Spain’s favor.

Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas’ rare Descripcion De Las Indias Del Poniente (1601) is the first printed Spanish map of Southeast Asia and a consequential political document. Herrera, the royal historian to the King of Spain, created the map as part of a historical work on Spanish colonies in the Americas and East Asia. In scope, the map covers China, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, the Spice Islands, and parts of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Persuasive Cartography and Competition between Empires

Herrera’s map is an early example of cartographic propaganda. While earlier maps and charts, as well as the logs and records of Spanish captains crossing the Pacific, played a part in this map’s composition, one of the aspects that makes Herrera’s map so intriguing is its use of the manuscript charts of fellow Spaniard Juan López de Velasco (compiled circa 1575-1580). Following Velasco, Herrera explicitly delineates the 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza for the first time on a printed map.

The Treaty of Zaragoza essentially renegotiated the famous 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. Ferdinand Magellan’s discoveries in the early 1520s made this renegotiation necessary. Each treaty established a Line of Demarcation, the geographical dividing line that defined whether new land came under the aegis of Portugal or Spain.

On Herrera’s map, this line descends through Central Asia and divides the Malay Peninsula. This positioning, which implies a Spanish territorial claim on the entire Cathay coast (China) and the Philippines and Spice Islands of Indonesia, was dramatically skewed in Spain’s favor and entirely out of sync with the agreement reached in Zaragoza.

Herrera stakes an obvious claim to Southeast Asia, but is careful not to divulge any compromising details. Both Portugal and Spain maintained strict policies of secrecy regarding their discoveries and colonial establishments, which is reflected in the lack of concrete detail. Despite its clandestine nature, the map remains a crucial document of the era due to its portrayal of Spain’s territorial ambitions in the region, and in particular, Herrera’s treatment of the Ladrones (Mariana Islands) and the Philippines, which Ferdinand Magellan claimed for Spain in 1521. These archipelagos have been drawn as clusters of islands, most numbered, referencing a key in the upper right corner. The key lists each of the islands by name, cementing that all the individual islands had been visited and thus claimed by Spanish fleets.

The Treaties of Tordesillas and Zaragoza

The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) was a landmark agreement between Spain and Portugal to divide newly discovered lands outside Europe. The treaty established a Line of Demarcation approximately 370 leagues (about 2,200 kilometers) west of the Cape Verde Islands. Lands to the west of this line were granted to Spain, while lands to the east fell under the aegis of Portugal. This effectively gave Spain rights to most of the Americas and Portugal rights to Africa, India, and eventually parts of Brazil. Although the treaty initially focussed on the Atlantic and the Americas, it would also have far-reaching implications for other regions, particularly Southeast Asia.

As global exploration expanded, Portugal exploited its rights to territories east of the Tordesillas line, establishing strategic trading posts and factories in places like Goa, Malacca, and Macau. These early colonial ventures were essentially made possible by the Treaty’s terms, but a lack of geographical knowledge soon meant that tensions between Spain and Portugal rose again. The instigating event came in 1521 when Ferdinand Magellan reached the Philippines after crossing the Pacific and claimed the islands for Spain.

Technically, Southeast Asia belonged to the Portuguese sphere, and Spain’s entry onto the scene prompted renewed conflict. The issue was mainly about controlling the lucrative trade with the Moluccas or Spice Islands. Spain and Portugal renegotiated their territorial claims in the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529) to resolve the dispute. This treaty established a new Line of Demarcation in the eastern hemisphere, drawn at 297.5 leagues (about 1,763 kilometers) east of the Moluccas. Under the Treaty of Zaragoza, Portugal won more permanent control of the Moluccas and much of Southeast Asia. For its part, Spain was compensated with 350,000 ducats and was allowed to retain the Philippines and all of its American colonies.

The new demarcation line ensured that Portugal would dominate the East Indies for most of the 16th century, while Spain focused on expanding its influence in the Pacific. Herrera’s map speaks directly to these complex political negotiations that saw Spain and Portugal divide the world in the 16th century.

Cartographer(s):

Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (1549–1626) was a prominent Spanish historian and chronicler best known for his comprehensive works on the history of Spain’s overseas empire. Born in Cuéllar, Spain, Herrera studied humanities and entered royal service, eventually becoming the official historian to King Philip II and later to King Philip III. In this capacity, he had access to a wealth of official documents and records, allowing him to compile detailed histories of Spain’s global conquests. His most famous work, Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Océano, is a monumental account of Spanish exploration and colonization in the Americas, stretching from the time of Columbus to the late 16th century.

Herrera was also responsible for producing important maps, such as his 1601 map of Southeast Asia, Descripcion De Las Indias Del Poniente, which revitalized Spain’s territorial claims in Asia. His works are considered critical sources for understanding the Spanish Empire, as they cover the Americas, the Philippines, and other parts of Asia. While criticized for favoring Spain, Herrera’s histories remain invaluable for their detail and scope. His works were widely read and translated during his lifetime, cementing his legacy as one of Spain’s foremost chroniclers of empire.

Condition Description

Very good.

References