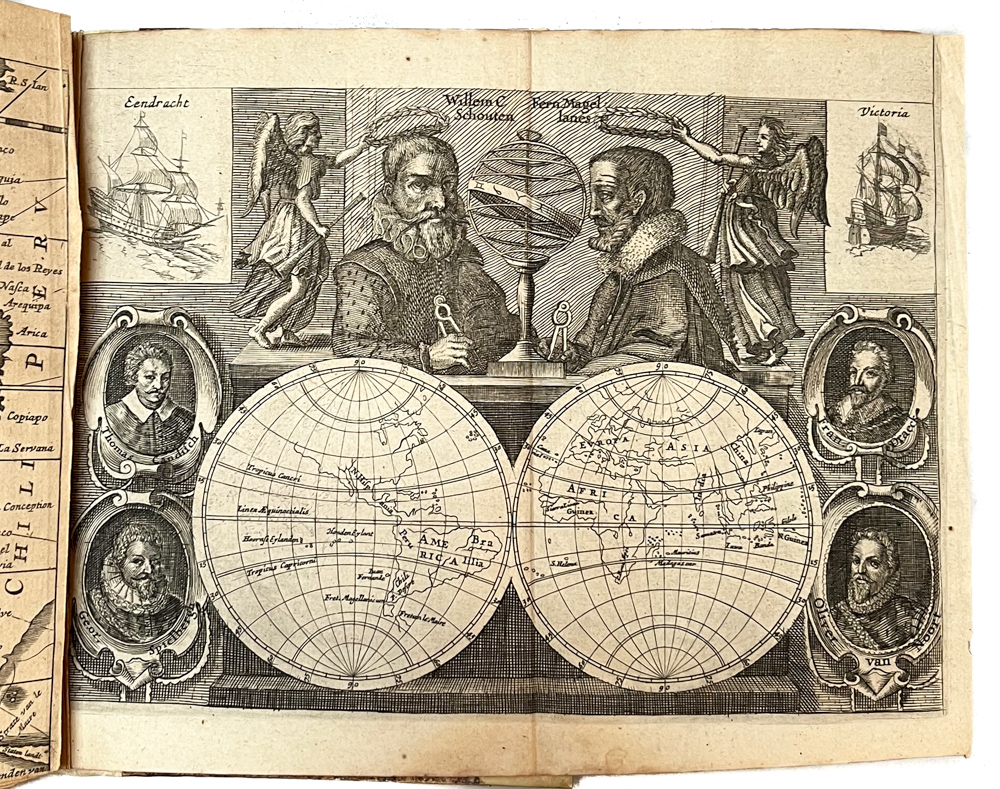

Stunning, full-color Coronelli map of the New World with California as an Island.

Planisfero Del Mondo Nuovo, Descritto Dal P. Coronelli, Cosmographo Publico.

Out of stock

Description

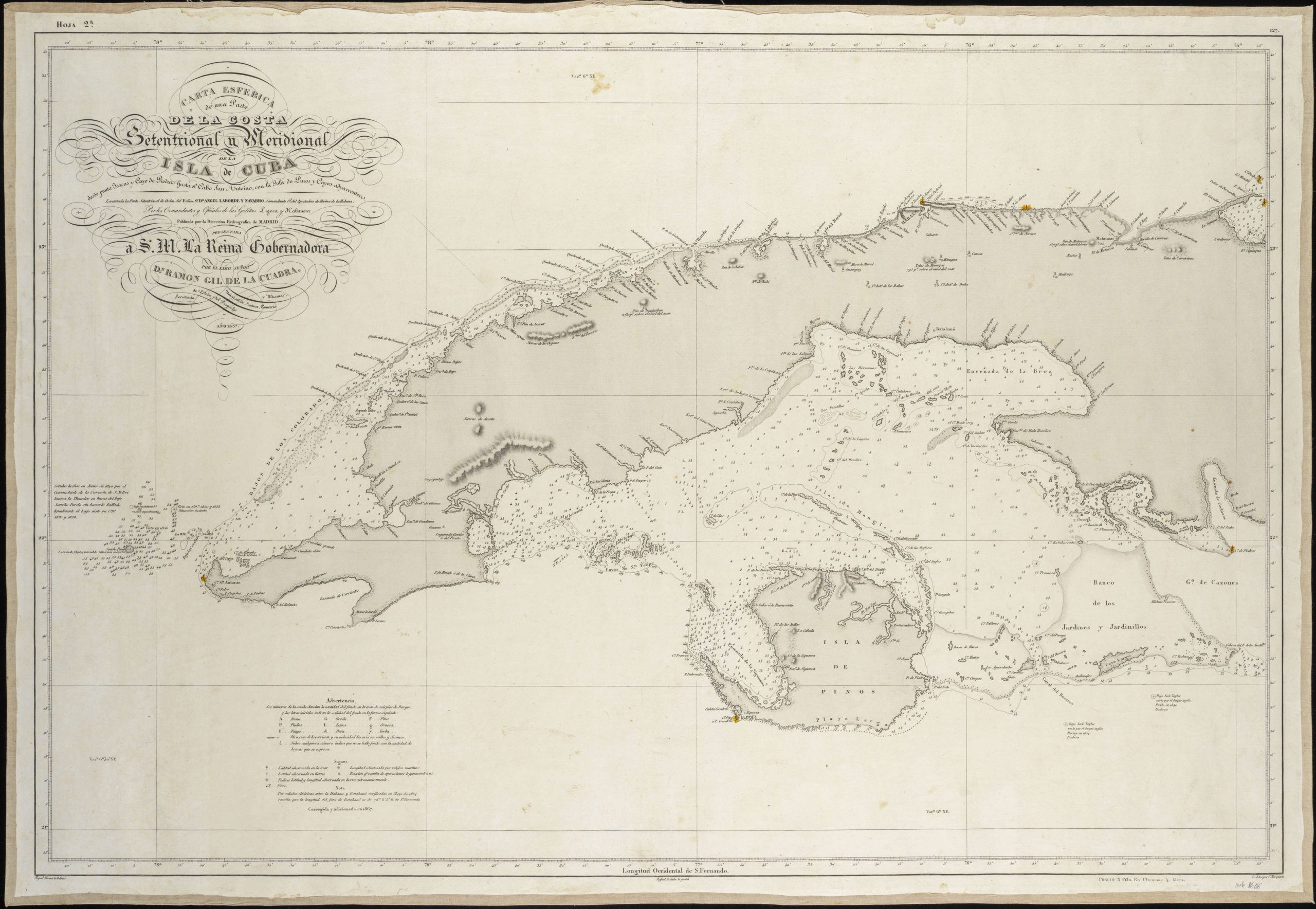

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli compiled this unique planisphere at the pinnacle of his illustrious career, combining the best geographical knowledge with the finest cartographic traditions. Coronelli’s gorgeous map reflects how cartographers grappled with a vast intermix of geographical knowledge and myth produced during the apex of global exploration.

Among the many elements that make Coronelli’s maps so important and collectible was his direct access to the latest French sources. This made him far more confident about inserting new features and pushing cartographical boundaries in his maps. These maps are no exception. Other appealing features include the decorative borders that enhance the aesthetic appeal and reflect Coronelli’s interest in astronomy and its relation to geography. This Old World map includes coordinates and descriptions of specific zodiacs along the outer rim of the chart, along with a triple band of latitudinal coordinates and meridians to complete the composition.

The map was created for Coronelli’s prestige project, the Atlante Veneto (1691), which he designed as a continuation of Willem Blaeu’s groundbreaking Atlas Maior. It was compiled in 1690, as indicated in the atlas’ frontispiece, but was not published until the following year. In addition to the compendium of geographical and scientific knowledge, the Atlante included an essential treatise on globe-making. Coronelli based this planisphere on his large globe gores from 1688 (Shirley 537), which presented the world from a distinctly Italian perspective.

California as an island

One of the most striking elements of Coronelli’s map is the depiction of California as an island. Following the second Sanson model, California is depicted as a fully isolated landmass, prominently labeled Isola California. This cartographic misconception was prevalent in European cartography from the early 17th to mid-18th centuries. Originating from the 1602 account of Sebastian Vizcaino, the myth gained traction and was perpetuated by prominent mapmakers such as Abraham Ortelius and Nicolas Sanson. Despite skepticism from other mapmakers like Guillaume De L’Isle and Johannes de Laet, who refuted the insular depiction, the notion persisted well into the mid-18th century.

The myth of California as an island carried significant implications, including a perceived connection to the Northwest Passage. Indeed, north of California, the geographic configuration quickly wanes into speculative outlines, including the mythical Stretto d’Anian that separates the Americas from Asia. As importantly, however, the myth questioned Spanish authority in the region. Even after Father Eusebio Kino had personally verified its connection to the mainland and published his description and map in 1705, the notion stubbornly persisted. The idea was gradually abandoned only after King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a decree in 1747 proclaiming California to be a peninsula connected to North America.

New Mexico and the Rio Grande

Coronelli’s gorgeous composition in the American West highlights Nuovo Mexico as Apache country. Coronelli published a seminal map of Upper Mexico and the Rio Grande (here labeled Rio Bravo) in 1688. This map followed Nicolosi’s groundbreaking model and was, at its publication, one of the most detailed and accurate maps of the American West available. Unsurprisingly, Coronelli also transferred the Rio Grande’s configuration onto this composition. The detailed information conveyed in Coronelli’s map came directly from Diego Penalosa, the Spanish governor of New Mexico (1661-63), who turned rogue and provided the French King with a wealth of strategic geographical information. His ambition was to lure the French into attacking New Mexico from the neighboring territory of Louisiana.

Remote Lands: East Asia and the Pacific

In addition to a stunning depiction of the Americas, Coronelli’s New World also includes other noteworthy features. Abel Tasman’s recent discoveries in Australia are shown, just as the map provides an early and somewhat ephemeral representation of New Zealand (including an erroneous note that the Dutch discovered this in 1648). While the Pacific region is generally rich in detail, featuring portions of New Zealand, Van Diemens land, Carpentaria, and Nuova Guinea, it also omits features like the Solomon Islands. Here, too, Coronelli is replicating the configuration from his large 1688 globe.

The treatment of East Asia and Japan is also noteworthy, including a large Terra di Iesso as the easternmost point. Here, too, the map includes an annotation that this was discovered by the Dutch, albeit in 1643. While this land bridge did not exist to begin with, the annotation also contradicts Iesso’s affiliation with Japan, where an official Dutch trading station had been established in the Bay of Nagasaki as early as 1609. This massive yet imagined landmass reveals the speculative nature of cartography in the 17th century.

Cartographer(s):

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli (1650 – 1718) was a Franciscan printer, cartographer, and globe-maker from Venice. Due to his religious background, many of his charts have been signed P. Coronelli, meaning Père or ‘Father’, and referring to his status as a friar of the Franciscan Order. He was appointed official cosmographer for the city of Venice and was later employed as royal cartographer to the King of France. In particular the latter position meant that he had access to the latest records and materials from French pioneers and voyages of exploration. This caused many of his charts to be cutting-edge innovations that redefined the newly discovered parts of the world in an entirely novel fashion. It also meant that Coronelli would have no scruples in declaring uncontested or virgin land in the New World as part of Nouvelle France. This is exemplified in Coronelli’s celebrated 1685 chart of Western Canada or Nouvelle France, in which the official French territories have been expanded thousands of miles to the west and south, so that most of the Midwest, including the Mississippi Valley, has been subsumed under a French claim.

Coronelli’s access to the latest French sources and intelligence is part of what has made his maps so cartographically decisive and collectible. An example of this is found in his 1688 chart of upper Mexico and the Rio Grande (modern Arizona, California, and parts of New Mexico). This map was, at the time of its publication, one of the most detailed and accurate maps of the Rio Grande on the market. The detailed information conveyed in Coronelli’s map came directly from Diego Penalosa, the Spanish governor of New Mexico (1661-63) who turned rogue and provided the French King with a wealth of strategic geographical information. His ambition was to lure the French into attacking New Mexico from the neighboring territory of Louisiana. Despite the controversial source of his information (or perhaps precisely because of it), Coronelli does not hesitate to lay credit where credit is due, and mentions Penalosa directly in the map’s cartouche.

Condition Description

Excellent.

References

Leighly 89; McLaughlin 105; Wagner 435; Shirley 548; Wallis 537