Seutter’s first state map of Pennsylvania, Jersey, and New York, with original color.

Pensylvania Nova Jersey et Nova York cum Regionibus Ad Fluvium Delaware…

$2,900

1 in stock

Description

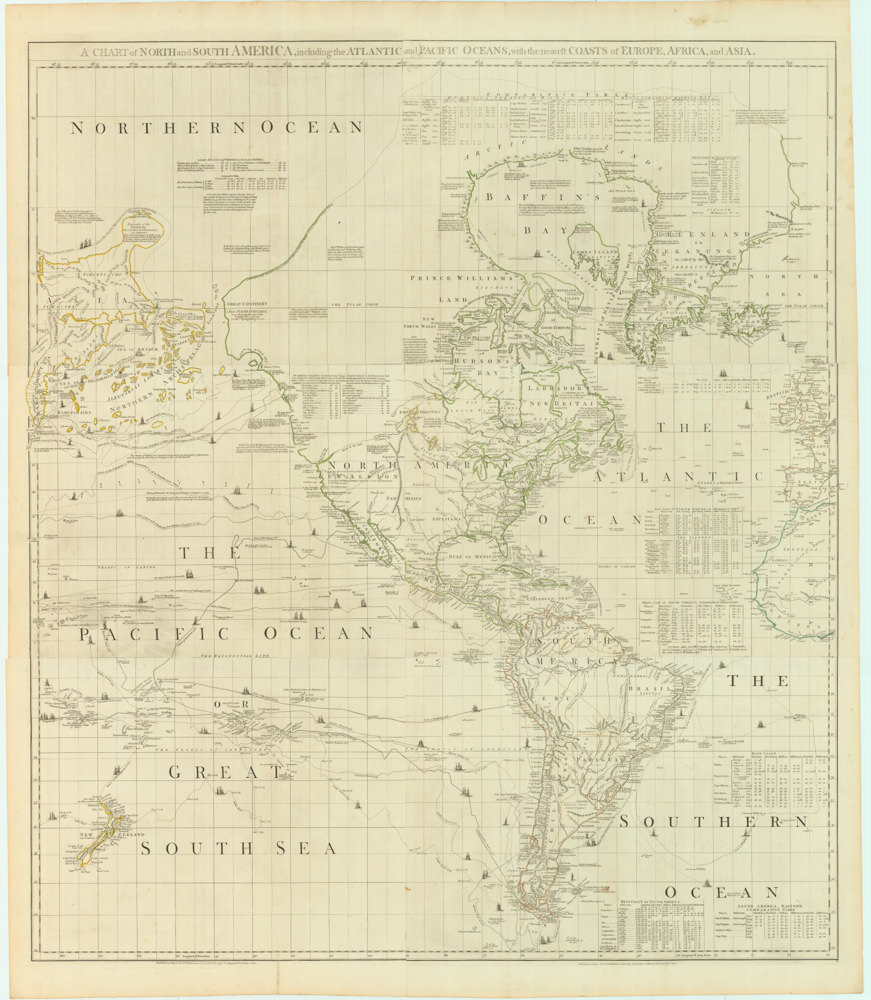

This mid-18th-century copper-engraved map of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York is the first Continental or European adaptation of Lewis Evans’s seminal 1749 map of the American colonies. It was reissued repeatedly by varying mapmakers, but this is the earliest available state of Seutter’s adaptation, and a keystone in any collection focused on America’s colonial past. The map is an elegantly composed depiction of the Middle Atlantic colonies that emphasizes settlements, communication lines, and physiography as much as administrative boundaries. It is printed on a single folio sheet with generous margins and set inside a double-rule border frame. Seutter’s adaptation of the map combines a dense topographical rendering with a decorative engraving style typical of German printers and publishing houses in the 18th century.

Census and bibliographic information

The German version of this map was produced in two principal publishing states (Seutter and Lotter), with a range of minor typographic variants. This makes identification of the state a primary concern. Modern authorities agree that Seutter’s sheet derives directly from Lewis Evans’s important Map of Pensilvania, New-Jersey, New-York, and the Three Delaware Counties, printed in Philadelphia in 1749. This was one of the first large-scale maps to incorporate survey data from the rural counties inland and thus soon came to serve as a cartographic template for the Middle Atlantic Colonies. Recognizing the seminal nature of Evans’s map, it was quickly pirated in Frankfurt and soon thereafter adopted by Seutter (with engraving by Tobias Conrad Lotter).

The principal Seutter/Lotter states can be distinguished using the following diagnostics:

- Cartouche and title-spelling variants: Several early examples show variant orthography, most notably Nova Iersey spelled with an initial I, versus the more familiar Nova Jersey. The archaic “Iersey” spelling appears in only a few examples of this map and is generally considered indicative of an early state. Yet while orthography is a strong indicator, it is not sufficient in isolation.

- Imprint and maker-name: A far more telling clue comes from the imprint. Early Seutter impressions include “per Matth. Seutterum” in the title, while impressions issued after 1756 – that is, after Tobias Conrad Lotter assumed full control of the business – bear only Lotter’s imprint. This change of imprint is one of the simplest and most consistent ways to distinguish Seutter states from Lotter states.

- Typographic variants: The successive printings also show slight variations in the typographic setting of place names, the content of the lower-right legend, or the wording of the title. However, these have not yet been systematically studied and categorized, forcing us to rely primarily on the elements noted above.

Bibliographic entries for this Seutter map vary in date. McCorkle (New England in Early Printed Maps) and other bibliographers commonly cite c.1750 as the most appropriate date for the confirmed Seutter’s editions, while later Lotter reissues are dated to the late 1750s and 1760s. That said, even the early Seutter sheets were engraved by Tobias Conrad Lotter, who is indeed acknowledged as the engraver on our sheet as well (lower right corner). The composition is stylistically consistent with other Seutter/Lotter collaborations dating between 1748 and 1756.

In sum, we may conclude that the present example is an early Seutter impression, realistically dated to about a year after Evans’s seminal map.

Composition and layout

The map is oriented north-south and extends from Lake Ontario and the upper Hudson valley in the northwest, across eastern New York, New Jersey, and eastern Pennsylvania, to the Chesapeake approaches in the south. The coastline is drawn in an exaggerated, pictorial style, with Long Island and the New England coast depicted schematically and truncated in some places. At the same time, the details of the inland are far richer. The map captures settlements, Indian villages, forts, principal rivers, and mountain ranges, rendered in rows of pictorial ridges. A dense network of place-names includes several small hamlets and townships that are uncommon on contemporary English maps of the colonies. The Delaware and Hudson Rivers, as well as portions of the Susquehanna and Schuylkill basins, are drawn prominently and used as organizing axes for both settlements and territorial labeling.

The engraving is highly detailed, with terrain shown pictorially with hachured hills and clustered mountains, and forests indicated by groups of small tree vignettes rather than symbolic blocks. Towns and settlements are differentiated by typography (larger capitals for principal towns, smaller type for villages) and by small pictorial devices (circles or tiny house marks). A keyed legend appears in the lower right and lists metropoles, large towns, market towns, and other settlement types. It also provides a scale in German miles and is topped by an attractive compass rose. The title cartouche occupies the upper-left quadrant and is an elaborate baroque composition, with an ornamental foliate frame surrounding the Latin title. The associated vignettes include genre figures such as European colonists and Native Americans, as well as agricultural and animal motifs, all arranged to dramatize the map’s colonial subject matter. Beneath the cartouche, European settlers interact with indigenous people on a pastoral backdrop. The combined use of Latin and German for toponymy reflects the map’s German-speaking target audience.

Surviving examples are often hand-colored in pale wash tones to delineate administrative divisions. In our case, New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, and the Hudson Valley counties are defined by soft pink and green washes, neatly contained by red or green boundary strokes. The plate impression is strong, reflected in the countless minute yet visible details and the clear lettering.

The map contains many colonial-era place names and ethnographic references, including Native American villages (rendered phonetically and, in many cases, based on contemporary English source maps). Short German captions describe the topography and identify passable roads or mountain ranges. Throughout, short descriptive inscriptions fill the map’s blank areas to identify important physical or cultural features. The sheet is particularly notable for the exceptional interior detail in Pennsylvania and the integration of colonial survey data, which was unusual on European maps before the 1750s.

Context is Everything

The 1740s and 1750s saw an accelerated geographic interest in the middle British colonies. On the ground, settlement had pushed westward from the Atlantic seaboard into the interior of Pennsylvania and the Hudson Valley. Proprietorial land divisions, frontier roads, interactions and conflicts with indigenous polities, and increased transatlantic migration, especially of German speakers, were all factors that helped stimulate a significant demand for detailed regional maps such as this. Lewis Evans’s 1749 map is a watershed in this regard, as it combined surveying data and local knowledge to depict interior settlement in ways that earlier coastal charts, provincial overviews, or generalized atlases had not. Evans’s map circulated rapidly and was taken up by European publishers who recognized both its novelty and its commercial utility.

Matthäus Seutter and Tobias Conrad Lotter operated in a German print and atlas market that actively consumed maps of the overseas colonies. German emigrants to Pennsylvania (the so-called “Pennsylvania Dutch”) were actually mostly German speakers, and these and other prospective emigrants were a significant audience for Seutter’s maps. Germanic publishers had a commercial incentive to reissue reliable maps of the Americas in German. This process involved both pirating and local reinterpretation. Thus, the Evans map was adapted, resized, relettered, and ornamented to appeal to German tastes. The Seutter sheet illustrates how knowledge about the colonies passed from colonial surveyors and printers to European mapmakers through an intermediary network of emulation, piracy, and legitimate republication. In practical terms, this meant that European audiences suddenly had access to insights that local surveyors and colonial settlers had long known.

The mid-century date puts the production of this map on the eve of the French and Indian War (1754–1763). Maps documenting frontier settlements, river approaches, and communication routes had immediate military, administrative, and propaganda value. Even as the Seutter map was sold as an atlas sheet or wall map in Europe, its underlying geography was of direct importance to colonial officials, soldiers, merchants, and prospective settlers planning emigrate to America. Its circulation thus helped shape European perceptions of the American colonies.

Cartographer(s):

Matthäus Seutter was born in Augsburg in 1678 and became one of the most prolific and influential German map publishers of the first half of the eighteenth century. Seutter apprenticed in Nuremberg under Johann Baptist Homann, a formative experience that shaped both his engraving technique and business approach. Around 1707, Seutter established an independent publishing house in Augsburg, which, over the following decades, grew into a major European cartographic firm. In 1731, Suetter was named Imperial Geographer (Geographus Caesareus) by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, further supporting his momentum.

Seutter’s firm was known for high-quality engraving, baroque cartouches, and for reproducing and adapting important foreign maps for the German market. After Seutter died in 1757, the business passed through family connections to his son-in-law, Tobias Conrad Lotter. Lotter continued to publish and reissue Seutter plates, sometimes altering imprints and ornaments to claim them more as his own. In general, Seutter’s practice exemplifies the commercial, collaborative, and often derivative nature of European cartography in the 18th century.

Condition Description

Staining and wear in the margins. Map image very nice. Original color.

References