Two of Bemporat’s iconic and monumental Argentinian wall maps: a stunning city plan of Buenos Aires and a national railway map.

Plano Comercial de la Capital Federal y sus Alrededores por A. Bemporat [AND] Gran Mapa de Ferrocarriles Sud Americanos compilado por A. Bemporat

Out of stock

Description

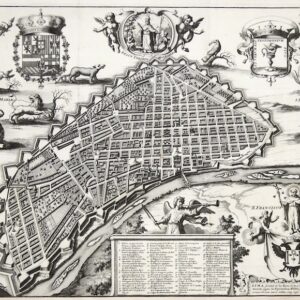

This pair of large and highly decorative wall maps was produced in 1914-15 by the offices of A. Bemporat, probably Argentina’s most important cartographic publisher in the early 20th century. They document the thrilling progress that Argentina had undergone during the late 19th and early 20th century, and encapsulate the spirit and vision that helped drive this development. The maps testify to the dynamism, optimism, and growth that characterized Argentina — and especially Buenos Aires — during this formative period.

Together, the two maps depict the entire country and its capital, capturing Argentina in a process of modernization that forever changed this South American nation. They were printed chromo-lithographically by the Bemporat company from their facilities in Juncal, just east of Buenos Aires, using a bold and very modern design template. They are folding maps on original linen and slide together neatly into their original dedicated case.

In both cases, the maps were visually enhanced with a range of features, including striking new fonts, lots of insets, and tabled data. The beautifully designed title cartouches on both maps are executed in a cutting edge Art Nouveau style, revealing that the Bemporat Company entertained some of the highest aesthetic aspirations in South American mapmaking, and that they employed the skilled draughtsmen to achieve them.

Dating the maps

Despite not being dated on the map, we know that the National Ferrocarril map was initially published in 1914, and reissued without changes in 1915. The Buenos Aires city plan is more tricky, as we have not been able to identify exact parallels in institutional collections. As mentioned, the urban plan fits neatly into the embossed case of the national railroad map, and they thus seem to have been issued as a pair.

The Bemporat Company generally produced a significant number of maps of Buenos Aires, many of which have been dated and figure in prominent institutional collections. By comparing our map to these, and to the degree of progress made in Buenos Aires in each map, we feel confident in claiming that our city plan also dates to around 1914-15 (increasing the likelihood that they were issued jointly). From 1914 onward, all Bemporat city plans of Buenos Aires included the large urban districts to the southeast of the original city, and the fact that these have not been included on our map suggests that it was compiled prior to the massive investment that went into developing these new neighborhoods.

On the other hand, the urban plan also shows the new commercial port, or Nuevo Puerto, located along the city’s eastern fringe. This enormous and crucial piece of infrastructure was not built until 1925, at first suggesting that our map could not be as early as we propose. However, the plans for the Nuevo Puerto were drawn up as early as 1907, and construction was formally approved in 1911 with the expectation that it would commence shortly. Corruption, dissent among decision-makers, and especially the First World War slowed plans down to a halt. It would take almost fifteen years for the grand project to be completed. Our city plan captures this incredible micro-history mid-process, with the port clearly conceptualized and present on the map, but probably bearing no semblance to reality at the time of printing.

The urban plan of Buenos Aires

In many ways, this stunning plan of the capital is the more important of the pair, in that it not only represents an important stage in the development of Buenos Aires, but also incorporates still unrealized ideas and enterprises into the extant urban fabric. It is as such not only a representation of Buenos Aires in the 1910s, but also a vision for the city’s future. It is both representative and aspirational at the same time. As a bonus, this seems to be one of the rarest urban charts of Buenos Aires produced by Bemporat, for we have not been able to locate other copies in institutional libraries and collections.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Buenos Aires was a place of considerable wealth. Argentinian producers and exporters were raking it in, attracting other heavy hitters who wanted a piece of the action. Consequently, vast wealth flowed into the city during the 19th century and this wealth manifested itself in opulent visions for the city’s development. The influx of money meant that the rich could build huge urban mansions in the heart of the city, often modeled on French chateaus (most of these still stand, but today function as government offices).

During the second half of the 19th century, Buenos Aires not only had experienced enormous economic gains, but also an exponential demographic growth. The main driver was the massive influx of immigrants from Europe (mostly from Spain and Italy, but also from Germany and Eastern Europe). At the same time, many of the people that during the early to mid 19th century had settled in the Argentinian countryside (including both immigrants and native Argentinians) now found it hard to make a living from cultivating the land and thus returned to the city to find work. The influx of people overwhelmed the authorities and inhabitants of Buenos Aires alike, and housing became a huge problem. Consequently, over the coming decades the city was intensively developed to accommodate the new population and grow its economy further. Entirely new neighborhoods were built and new infrastructure projects conceived that would make both production and export more streamlined and profitable.

Due to the already significant wealth present in the city, and the desire on the part of the Argentinian elite to convert Buenos Aires to a world-class capital, the conditions for the city’s planned growth were in place. Buenos Aires was to be the Paris of South America. This was not only meant figuratively, but also included a literal dimension, in which the overall urban planning strove to emulate the French capital. In preparation for the centennial of Argentina’s independence in 1910, the city council instigated enormous infrastructure projects all around the capital. These included the construction of an extensive metro and the plotting of urban space along a series of major boulevards that radiated out from the city centre — exactly as Georges Eugene Haussmann had done for Paris under Napoleon III.

The plan shows the heart of the old city transformed to a modern urban metropolis. Most of the streets have clearly been laid out according to a grid plan. The revamping of Buenos Aires manifested itself in the construction of broad avenues for every four blocks east to west, and every ten blocks north to south. The individual blocks are interspersed with parks and plazas and interconnected by large boulevards that run the length and width of the city. We are beginning to see the manifestation of this vision in our plan, which in many ways constitutes a snapshot of the city’s expansion mid-process. In our map, the extant urban sprawl (colored pink) already follows the gridded layout and is interconnected by large avenues like Rivadavia, Buedo, and Chiclana. Colored in yellow we find the many new blocks envisioned along these avenues and in extension of the extant urban plan.

The plan also includes a number of insets. In the lower left we find a regional map of Buenos Aires and its surroundings, showing how the city was being connected to the highly productive hinterland through infrastructure and administration. Next to it we find a charming little historical plan of Buenos Aires as it was in 1810. This is almost like a badge of national pride and honor, underlining the immense changes that the city had undergone since independence. In the lower right corner, we find a series of seven smaller maps showing the subdivision of the city into different administrative categories, including: military and police jurisdictions, as well as civil, judicial, and school districts. The lower left map of the seven is perhaps the most interesting in that it represents the “division poligonal,” which is a reference to the planned expansion of the city center during the period in question.

The urban renovation also included plans for ‘the broadest avenue in the world,’ named 9th of July for the Argentine day of independence. This was to be directly modeled on the Champ-Élysées, but would outdo it in scope and dimensions. The 9th of July Boulevard does not figure on our map, as work on it was significantly delayed by the First World War. It was only was commenced in 1930, and completed in 1937, many years after this map was published.

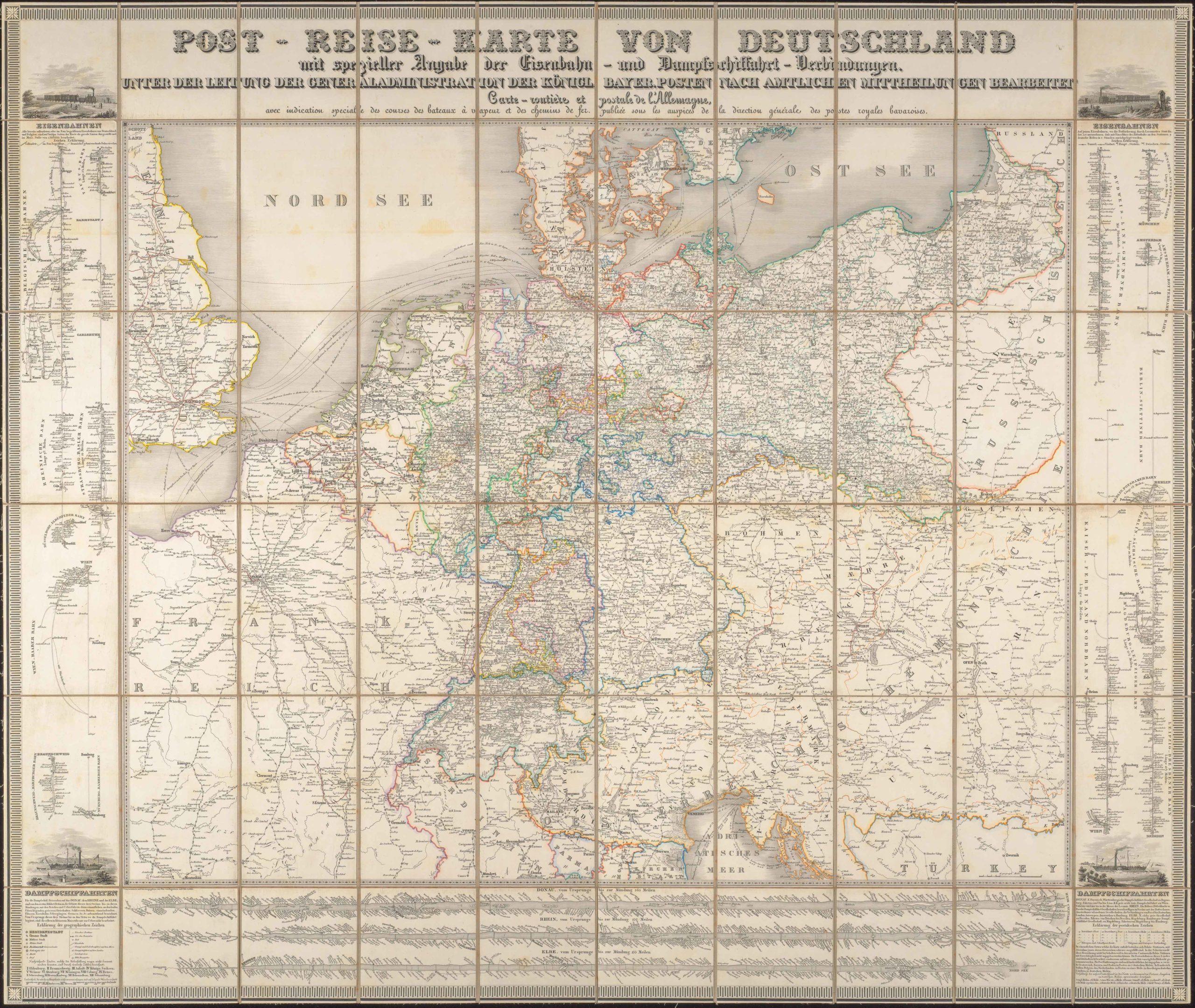

The railroad map of Argentina

The second map in our pair is the 1914 railroad map depicting of Argentina in its entirety, but also showing the neighboring nations of Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay, as well as southern Bolivia and Brazil. The map’s primary purpose is to display the railroad systems of Argentina, although the extant railway lines of Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile, Bolivia, and Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) have also been included on the map. Unlike most of the other national lines, there is an obvious focus on Buenos Aires in the Argentinian network. This is the hub from which nearly all railway lines extend. In many ways, the national pattern of infrastructure (railroads) mirrors the concept applied in the capital (street grid); both essentially follow a pattern of radiating lines from a central place.

The map is incredibly detailed, including not only the national lines, but also smaller rural networks. As is common for many large countries where railway was introduced as a crucial means of infrastructure, there is a rather dense network in close proximity to the capital. This density drops the further one moves away, and in the south of Argentina, there are hardly any railways at all. Only two stretches cut across the pampas, linking up the coastal networks with the Rio Negro Valley in the south and the frontier town of Zapala further north. In the deep south, another two small lines have been depicted, including their prospective extensions.

In the lower right corner of the map we find no less than seven insets depicting the urban rail systems in and around Argentina’s biggest cities, thus solidifying the general usefulness of this map no matter where in Argentina one wished to travel. Above the insets is the beautiful title cartouche, which is another great example of the modernistic aesthetic that Bemporat was striving for, and which is also reflected in the choice of fonts and its color scheme.

Cartographer(s):

The Oficina Cartografica Bemporat was an eminent cartographic publishing house based in Buenos Aires. The Bemporat firm were specialists in producing large printed maps of all of South America, but with a particular focus on Argentina and Buenos Aires. Their maps include regional and national charts, railways maps, as well as detailed renditions of urban centers – in particular South American capitals. The Bemporat series on Buenos Aires stands out as particularly seminal, in that they capture the rapid development that the city underwent in this period.

Condition Description

Minor wear along folds and the case.

References

University of Buenos Aires’ archive of historical plans: https://sites.google.com/view/ba-en-cartografia/página-principal