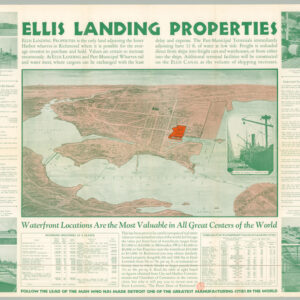

A dramatic bird’s-eye-view of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Authorized Birds Eye View of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Seattle, U.S.A. 1909.

Out of stock

Description

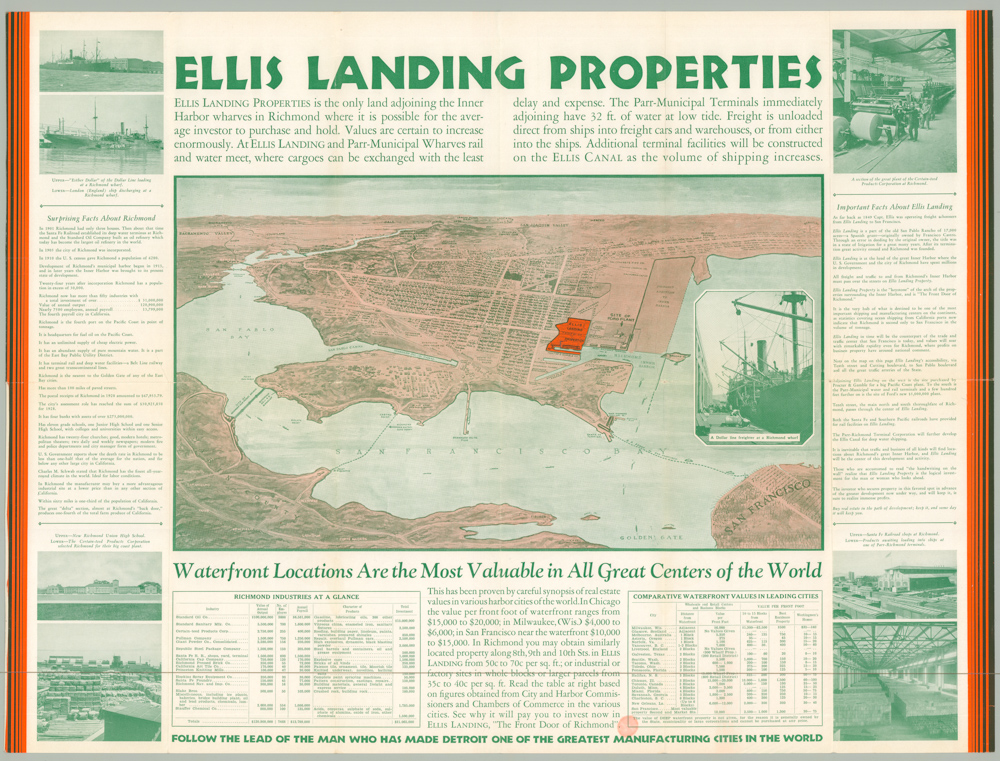

An incomparable document of Seattle history, this extremely rare and deeply evocative broadsheet offers one of the most incredible views of the city ever produced. It depicts the large and newly developed promontory into Seattle’s Union Bay, which today houses the University of Washington. The stunning vista was commissioned as part of the grand Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, held in this area from June to mid-October, 1909. Drawn by William Caughey, the view was printed as a chromolithograph by the Schmidt Label & Lithography Company, a German-American publishing house based in San Francisco.

The pristine fairgrounds pictured serve as a manifestation of Washingtonians’ ambitions for growth and development, and encapsulate the popular enthrallment with expositions in an age marked by great strides and rapid progress. The panorama promotes the splendid beauty not just of Seattle, but of the Northwest Pacific in general. As if to cement it all, the majestic peak of Mt. Rainier rises imposingly on the horizon, beyond the blue expanse of Lake Washington.

Of greatest interest to many is the fact that the view captures the inception of the University of Washington campus as we know it today. University Regents relocated the campus to this area in 1895, but it was sparsely developed in 1909, when Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition organizers targeted it as the ideal location for their upcoming fair. An agreement was reached and detailed site plans and new constructions were drafted, in part by John Charles Olmsted, the nephew and adopted son of Frederick Law Olmsted, America’s most famous landscape architect. The layout and sight lines that make the campus among the most beautiful in the world were formulated as a direct result of the exposition.

The view centers on the Great Hall or U.S. government pavilion, which back then was fronted by a small aquarium. Behind it, Government Hall and the elongated Cascade Court stretches down to the monumental rotunda known as the Arctic Circle. Flanking the court we find the pavilions for Alaska and Hawaii; lending clear symbolic importance to two of America’s most distant territories, neither of which had achieved statehood yet. At the center of the rotunda is an enormous fountain in a circular basin. This was designed to emulate a geyser and still survives to this day in the form of Drumheller Fountain. The two buildings encircling the Geyser Basin were dedicated to manufacturing and agriculture. Beyond the Arctic Circle, the gardens of the still extant Rainier Vista Park point directly towards the great peak. On either side of these we see the Japanese and Canadian pavilions, which unfortunately no longer survive.

Cutting a perpendicular axis across the Cascade Court, but still circumnavigating it, is a large pathway or thoroughfare named ‘Yukon Avenue.’ This corresponds roughly to present-day NE Grant Lane, at the heart of the University of Washington campus. On our lithograph it is clear how this road connects two circular piazzas on either side of the court, each with a small pavilion or bandstand in the middle. These circles were entitled ‘Nome’ and ‘Klondike’ respectively, in recognition of the pioneering Alaskan settlements. Along the eastern fringes of the exposition area, near the Union Bay coastline, we find the large forestry building in red brick; just in front stands the yellow California pavilion, built in the characteristic low-lying style of a Californian hacienda or ranch.

Context is everything

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was the greatest world’s fair ever to be held in the Pacific Northwest. In addition to the overall attention that such fairs lent to host cities, the goal of this particular exposition was to promote the widespread development that had characterized the region since the 1890s. A major driver behind the rapid development of the NW Pacific had been the discovery of large gold deposits along the Yukon River in Alaska, and the subsequent gold rush that centered on the frontier town of Klondike. Following the discovery, Yukon Territory attracted a huge number of prospectors, entrepreneurs, and other soldiers of fortune.

Just like the 1849 gold rush had helped shape modern California, and especially San Francisco as the gateway city that linked the interior to the rest of the world, so Seattle hoped that the discovery of gold in the Yukon might help stimulate an economic boom in the Pacific Northwest, with Washington’s great port acting as a gateway to the rest of America. The choice of Seattle as the venue for this fair was natural. No Alaskan city or town could at this stage garner sufficient attention, nor attract the necessary amount of visitors and sponsors to compete with similar fairs throughout the country. The focus on America’s northernmost wilderness and its potential nevertheless remained a cornerstone of the fair.

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition had originally been planned as an event denoting the tenth anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush, which took off in 1898. But this date would have conflicted with the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. Consequently, it was decided to push it back one year, leading to a 1909 date instead.

The broad sheet is not only a beautiful and incredibly rare depiction of Seattle’s newest and most pristine neighborhood at the dawn of the 20th century, but it is also a vivid reminder of just how popular these world fairs had become in America during the 1900s. Expositions such as this one were the ideal venues for showcasing a city’s or region’s ingenuity, drive, and progress in an age when such characteristics meant everything, and every city with ambitions sought to host one, often with no costs spared.

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was a major event in the history of Seattle and unlike so many fairgrounds from this era (e.g. Chicago, San Francisco), many of its vestiges have been preserved for posterity, in that the fairgrounds were converted into the campus of the University of Washington shortly after the exposition ended. Alumni and other people familiar with the UW campus grounds will thus easily be able to pick out the university’s major landmarks, here depicted only months after they had been erected. It is, in essence, one of the most important and telling views of early 20th century Seattle available on the market.

Census and rarity

The first example offered on the private market of which we are aware. The OCLC lists copies at Yale University, Washington State Library, and the University of Washington. We have identified additional institutional copies at Washington State University (https://content.libraries.wsu.edu/digital/collection/maps/id/52) and The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley (https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/tf909nb8sb/).

Cartographer(s):

The Schmidt Label & Lithography Company was an American publishing house based in San Francisco and which specialized in the printing of labels (although separate prints also were issued). It was founded in 1873 by a German immigrant, Max Schmidt. Schmidt was one of the first West Coast printers to use the lithographic technique, giving him a distinct advantage over his competitors and cementing his success. By the 1890s, he ran a factory in the city as well as branches in Portland and Seattle. Despite facing severe set backs, including several fires and the complete destruction of his plant in the 1906 earthquake, Schmidt was an extremely resilient and innovative businessman. Within a few years of the 1906 devastation, the Schmidt Company had become one of the largest printing houses on the West Coast.

Condition Description

Restored, retouched, backed on archival tissue with a minute spot of facsimile.

References