Four technical maps focussing on urban infrastructure and water supply and one engineering blueprint for a new fireboat, together reflecting San Francisco’s coordinated response to the devastation of the 1906 earthquake. With an interesting provenance.

5-sheet set showing San Francisco’s post-1906 earthquake water supply [SF’s first fireboat!]

$8,500

1 in stock

Description

This gorgeous set of five technical sheets was issued as supporting material for a detailed engineering report that proposed a comprehensive fire combatting infrastructure for the city of San Francisco. The report and associated maps, titled ‘Reports on an Auxiliary Water Supply System for Fire Protection for San Francisco, California,’ were compiled by city engineer Marsden Manson following the catastrophic devastation of the 1906 earthquake. While the 173-page technical report has not survived in this case, the five pristinely preserved sheets embody its drive and spirit and represent some of the grand ideas being entertained in the rebuilding of San Francisco.

The report provided the city council with a complete technical analysis of San Francisco’s standing capacity and a comprehensive proposal for elaborating and extending it considerably. This report was published in 1908, only two years after the catastrophe, demonstrating the resilience and drive of San Franciscans. The goal, of course, was to make San Francisco less susceptible to the type of extensive urban conflagration that followed in the wake of the earthquake.

The five map sheets were lithographed by the Britton & Rey company and consist of four thematic maps and the engineering blueprints for a fireboat for the San Francisco Fire Brigade. In unison, the set not only speaks to the impressive organizational capacity of post-earthquake San Francisco and highlights the crucial role played by technology and engineering in the recovery. Thus, while these sheets were conceived within the strict framework of safeguarding the city against fires, they have since become emblematic of America’s great engineering legacy.

The four maps included in this set are essentially identical in scale, street template, dimensions, etc. What distinguishes them from one another is their thematic overlay, which illustrates specific points in the overall plan that the report constitutes. Below is a brief description of the contents and significance of each sheet in the set.

Sheet No. 1: Showing Arrangement of the Distributing System and Location of Hydrants, Reservoirs and Pumping stations.

This first sheet is the most comprehensive in that it shows multiple related features. The mapmakers employ color swathes to subdivide the city into three zones of terrain: firm ground in the Lower Zone (yellow), firm ground in the Upper Zone (Blue), and then areas within the Lower Zone where subterranean piping is likely to burst in the event of an earthquake (green). The latter demonstrates that the most vulnerable areas were found around the infilled harbor front and stretching inland towards the Mission District. Throughout the city, underground piping of a potential new water management system is indicated in color-coded lines that also inform us of the size of the mains. The legend further defines several symbols that provide the precise location of controlling valves and hydrants.

Sheet No. 2: Showing of Location of Call Boxes and Central Stations of Proposed Telephone System.

We are treated to a clean copy of the base map in the second sheet, enhanced only by a single thematic feature. In addition to showing the street grid in considerable detail, red dots on every block mark the presence of new call boxes that allowed citizens to report fires directly and immediately. A rapid response dramatically reduced the risks of the fires spreading, but the system also meant that San Francisco would be equipped with some of the most sophisticated communication infrastructure in the nation. In addition to being an efficient means of combatting fires, the call box system involved citizens in their community, making it everyone’s responsibility to help avoid conflagration catastrophes in the future.

Sheet No. 3: Showing Location of Existing Cisterns and Preliminary Locations of 65 of the Proposed Cisterns.

The third sheet plots San Francisco’s cisterns before and after overhauling the city’s water supply system. This map uses a three-color dot system to locate all functioning urban cisterns, distinguishing them by cisterns in commission (green) and cisterns requiring repairs (blue). A number printed in the same color adjacent to each dot reveals the capacity of each cistern in units of one thousand gallons. The map also shows the 65 proposed new cisterns throughout the city (marked by red dots), dramatically expanding storage capacity. The map evinces how sweeping was the task of improving the water management of San Francisco.

On a more subtle level, this map also reveals the enormous demographic expansion occurring during the late 19th century. Whereas the original cisterns are found in a concentrated band from about Russian Hill to Yerba Buena, the new system of cisterns is distributed evenly throughout the entire city, securing for further generations both water supply and the means of combatting fires. In this sense, the mapmakers presage the water supply issues that would lead to the construction of the O’Shaughnessy Dam and the resulting creation of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. Britton & Rey were ideally suited to produce this map, having previously compiled and issued maps focussing on the city’s cisterns and water supply.

Sheet No. 4: Showing general plans for San Francisco fire boats.

Sheet 4 contains detailed engineering blueprints for a steam-powered fireboat. Indeed, the city did build a vessel shortly after the report’s publication. The fireboat was named the David Scannell (after the city’s first official fire chief) and was launched in May of the following year. Later that same year, a second fireboat was launched, built on the same design. The haste to realize these plans was closely tied to the lack of such a vessel when the earthquake struck in 1906, obliging the US Navy to send their fire vessels to San Francisco to aid in the extinguishing efforts. The investment was shrewd, and both fire vessels served the city faithfully until being decommissioned in 1954.

Sheet No. 5: Showing Locations of Breaks in Mains of the Spring Valley Water Co., The Fire Limits, and the Boundary of the District within which Fireproof Roofs are Required.

The fifth and final sheet in the set suggests that San Francisco’s recovery also meant its modernization. In this map, we essentially become privy to two distinct city zones, one relating to the past and the other to the future. The first feature shown by this map is the extent of fire damage from the earthquake. Like the water supply map concentrating on cisterns, this was a genre of thematic map that Britton & Rey had produced before. They issued a map delineating the extent of conflagration shortly after the disaster.

Among the many precautions taken by the city to prevent a similar disaster from occurring again, city officials defined a zone of inner-city housing within which the roofing of each building had to be fireproofed (marked in blue). The goal, of course, was to avoid flying embers starting new fires, and on the map, we immediately see how the zone of fireproofing dramatically exceeds the original scope of fire damage following the 1906 earthquake (marked in orange). The result is a clear visualization of the effort to expand San Franciso’s firefighting readiness. Throughout the map, red dots provide the exact locations of breaks in the water mains of the Spring Valley Water Company as a result of the earthquake.

Provenance

As can be seen in the image below, these maps seem to have been a set of duplicates that was mailed to a certain A. Leonard Jr, M.D. in San Francisco. We assume this is Alexander Thomas Leonard Jr., M.D. (1889-1970), a trustee of the California Historical Society. The set must have been extra, not attached to the report, and mailed to Leonard because he had an interest in San Francisco history. They were kept in pristine condition.

Context is everything

The San Francisco earthquake struck in the early morning hours of April 18, 1906. Soon after the tremors had abated, more than thirty fires broke out across the city and raged for days. Ruptured gas mains caused most fires, but local firefighters inadvertently started them in some cases. The fires burned intensely, and since most residential buildings were built of timber and brick, entire neighborhoods burned to the ground. Historians estimate that 90% of the destruction caused by the earthquake resulted from the fires. Many San Francisco landmarks were lost, including the famed Palace Hotel and City Hall. More than 80% of the city had been destroyed when it was all over, and more than 3000 people had lost their lives. The quake was felt as far away as Nevada, Oregon, and Los Angeles. The extent of the damage meant that two-thirds of the population became refugees overnight, and tents and shacks soon began to shoot up on the Presidio, in Golden Gate Park, and North Beach. Eventually, many refugees moved across the Bay to Oakland and Berkeley.

In addition to the immediate impact on the city, the earthquake also had more long-term consequences. Before disaster struck, San Francisco was not only the largest and most populous city on the West Coast, but it was also the most important port and the bridgehead for American mercantile interests in the Pacific and Asia. The destruction of basic infrastructure and the chaotic conditions to supply a workforce made maritime engagements difficult. As a result, trade was diverted south to Los Angeles and with it followed money and people. In effect, and despite an impressively efficient rebuilding process, San Francisco lost its position as California’s major urban center and would not regain it again.

The people of San Francisco nevertheless reacted with strong resilience to the calamity, and an efficient organization and progressive thinking marked the rebuilding process. The latest technology and machinery were applied in both the clean-up and rebuilding process, underscoring the modern outlook of the city and the widening scope of things like steam technology. An essential part of the rebuilding process was ensuring that such devastation would never occur again, even in the wake of an earthquake, and that is precisely what the report in which this set was issued strived to achieve. The ubiquitous installment of phone booths as a fire combating measure would provide the infrastructure for the much more elaborate use of telephones in the coming decades and helped put San Francisco at the forefront of the technological revolution. Similarly, installing a modern water distribution system throughout the city and securing stable reservoirs of accessible water helped create the hydrological infrastructure that could sustain the massive population growth of the 20th century.

Britton and Rey – Pioneers with experience

It is not surprising that the city chose the local firm of Britton and Rey to compile the large charts for this critical report. Branding themselves as ‘The Pioneer Lithographers of Greater San Francisco,’ not only were they well-renowned, but the firm had been at it for more than five decades. During their many years in the business, Britton & Rey issued a range of maps that now helped form the foundation for these new and crucial charts.

A 1906 map that charted the extent of conflagration following the earthquake was among the precursors. More importantly, perhaps, they had completed several mapping projects in the past, focusing specifically on San Francisco’s water supply and distribution. In 1894, for example, Britton & Rey issued an advanced technical chart that showed the Water Service of the Spring Valley Water Works (whose destroyed mains were plotted in Sheet 5 of our set). In addition to contour lines and topographic elevation, this map showed elements like distributor reservoirs and the districts they supplied, the location of principal water mains throughout the city, and the locations of fire departments and fire patrol buildings throughout the city. The fact that Britton & Rey could compile technically advanced maps was key to their involvement in this enormous post-earthquake project. And once again, they met their target, creating five grand visualizations that synthesize all the efforts that had gone into protecting San Francisco and her citizens in the future.

Cartographer(s):

Britton & Rey (1852 – 1906) was a lithographic printing firm based in San Francisco and founded by Joseph Britton and Jacques Joseph Rey in 1852. Especially during the second half of the 19th century, Britton and Rey became the leading lithography firm in San Francisco, and probably California. Among their many publications were birds-eye-views of Californian cities, depictions of the exquisite landscapes, stock certificates, and no least maps. While Rey was the primary artist, Britton worked not only as the main lithographer but was essentially also the man running the business. In addition to their own material, the firm reproduced the works of other American artists like Thomas Almond Ayres (1816 – 1858), George Holbrook Baker (1824 – 1906), Charles Christian Nahl (1818 – 1878), and Frederick August Wenderoth (1819 – 1884). Following Rey’s death in 1892 Britton passed the form on to Rey’s son, Valentine J. A. Rey, who ran it until the great earthquake and fire of 1906 destroyed most of the company’s assets.

Joseph Britton (1825 – July 18, 1901) was a lithographer and the co-founder of the prominent San Francisco lithography studio Britton and Rey. He was also a civic leader in San Francisco, serving on the Board of Supervisors and helping to draft a new city charter. In 1852, he became active in lithography and publishing, first under the name ‘Pollard and Britton,’ and then ‘Britton and Rey,’ a printing company founded with his friend and eventual brother-in-law Jacques Joseph Rey. Britton and Rey became the premier lithographic and engraving studio of the Gold Rush era, producing letter sheets, maps, and artistic prints.

Jacques Joseph Rey (1820 – 1892) was a French engraver and lithographer born in the Alsatian town of Bouxwiller. At the age of about 30, he emigrated to America, eventually settling in California. Here, he soon entered into a partnership with local entrepreneur and civic leader Joseph Britton. Three years later, Rey also married Britton’s sister, allowing his business partner and brother-in-law Britton to live in their house with them. Rey and Britton were not only an important part of the San Francisco printing and publishing scene but also owned a plumbing and gas-fitting firm. In the early years, both men would sometimes partner up with others on specific projects, but by the late 1860s, their partnership was more or less exclusive.

Condition Description

Superb. Folding maps.

References

OCLC #613115538; https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044044460483&view=1up&seq=12&skin=2021

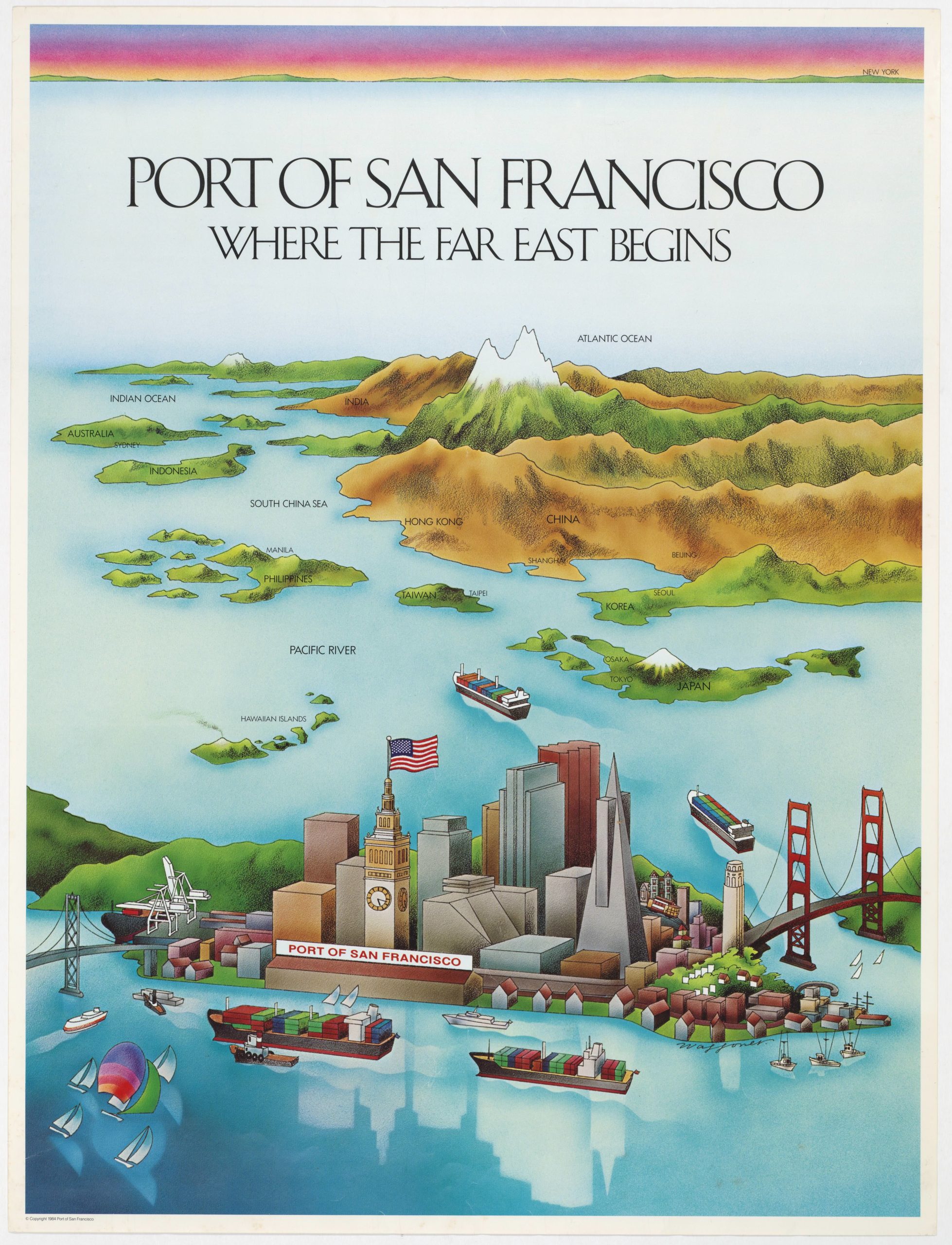

![PORT OF SAN FRANCISCO. WHERE THE FAR EAST BEGINS [Japanese language version]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NL-00879_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![PORT OF SAN FRANCISCO. WHERE THE FAR EAST BEGINS [Japanese language version]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NL-00879_Thumbnail.jpg)