The Dutch edition of Guillaume de l’Isle’s seminal map of North America, which saw one of the first attempts at rectifying the erroneous notion that California was an island.

L’Amerique Septentrionale Dressee sur les Observations de Mrs. de l’Academie Royale des Sciences & quelques autres, & sur les Memoires les plus recens…

Out of stock

Description

An excellent old color example of Pieter Schenk’s edition of the ground-breaking North America map by French master-cartographer Guillaume de l’Ilse.

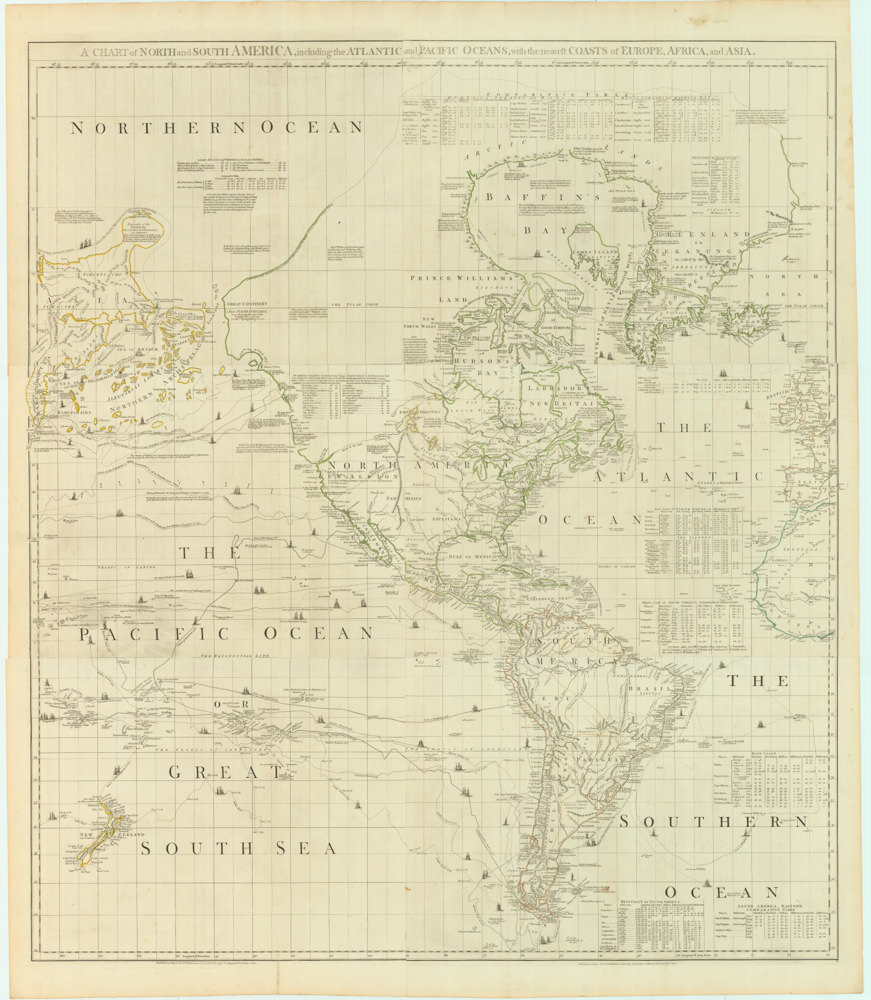

Originally published in Paris in 1700, de l’Isle’s map was fundamental to the development of geographic understanding of North America in the 18th century. Its most enduring legacy is perhaps that it was the first European map to begin correcting the commonly accepted myth that California was an island. The map also constituted a new endeavor to cover all known areas of the uncharted continent, with information gleaned from French, English, Dutch, Spanish, or Italian sources. Consequently, we find detailed early renditions not only of California but also of the Great Lakes region based on the maps of Coronelli and the inclusion of critical locations in the French territories of both Florida/Louisiana (e.g. Boulaye and Biloxi) and Canada (e.g. Quebec, Fort Sorel, Tadousac, and Montreal).

Starting in the east, we find a detailed coastline from Baffin Bay down to the Spanish Main. A significant portion of the Atlantic has also been included, particularly the Sea of Sargasso and the archipelago of the Azores. This inclusion was not coincidental but rather added because among de l’Isle’s many cartographic innovations in this map was the reconfiguration of North America’s longitudinal positions, as calculated from the Azores. As a result, de l’Isle was the first mapmaker to create a printed map focussing on the Sargasso Sea.

There are many other exciting details to note along the eastern seaboard. As with most American maps from this period, de l’Isle’s map had an overtly political dimension in that authoritative maps often helped cement contested borders. We see this emphasis on the current state of borders in the depiction of English settlements along the coast. These are mainly hugging the coast and are generally confined to an area east of West Virginia’s Allegheny Mountains. This subtle but important emphasis on borders is also seen in the inclusion of the fort and river named Kinibeki, which despite lying well within British domain, often served as the functional border between the colonies of New England and French Acadia. The gorgeous original coloring makes this dividing line even more apparent in our specific example.

In the south, the correctly placed Mississippi Delta follows the recent explorations of Sieur de La Salle and Sieur d’Iberville. From the Gulf, the great river cuts like a spinal column through the American continent until we locate its origins in the Sioux-dominated frontier of northern Minnesota. As in the north, French dominance in Greater Florida is made palpable by the inclusion of key outposts like Sieur d’Iberville’s settlement at Bilochy (a.k.a. Fort Maurepas/Old Biloxi) and important frontier forts like Boulay (de St Esprit) and St Louis. These strongholds were established in 1699-1700, following the latest French exploration of the delta the year earlier. Thus, their inclusion on this map demonstrates how well-informed he was as a cartographer. Further to the west, we find the Rio Bravo delta, which extends far inland, reaching the villages of interior New Mexico.

The west coast is in many ways even more exciting than the east and south, partly because this region of the Earth remained so poorly understood by Europeans at this time. North America’s western coast extends from the Panama isthmus in the south to Cape Mendocino in the north. The latter is clearly labeled and only constitutes the westernmost bluff of California. It lies far enough north to cement the notion that California was a peninsula rather than an island. Beyond Cape Mendocino, one ventures into the vast unexplored frontier of the Pacific Northwest.

Schenk published this edition in Amsterdam only eight years after de l’Isle’s original, reflecting the map’s landmark importance. While Schenk may have appealed to Dutch and English markets, French interest remained just as steady; thus, we see Pierre Mortier of Paris also issuing a new edition of de l’Isle’s map the same year as Schenk. Today, scholars studying the history of geographic awareness consider de l’Isle’s map (and by proxy Schenk’s and Mortier’s new editions of it) a milestone in the history of cartography. It was a map that would prove pivotal in defining cartography’s role in the new century, and it is not surprising that a renowned expert like R.V. Tooley refers to it as ‘a foundation’ in his French Mapping of the Americas (1966).

Neatline’s copy of this seminal map is particularly attractive. And not just because it has been preserved in excellent condition, but because it retains a vivid original coloring that brings the map to life.

Cartographer(s):

Guillaume de l’Isle (1675-1726) was a French cartographer who was a key figure in the transition toward a more scientifically grounded cartography.

He was renowned for the extraordinary quality and accuracy of his maps. Especially his depictions of North America stand as some of the most critical milestones in mapping the continent, as they were based on the most up-to-date information available and had been culled of all mythical or imagined augmentations. De L’Isle also recalculated latitude and longitude based on the most recent celestial observations and incorporated these revisions onto his maps. In doing so, he set new entirely standards for cartographic accuracy.

De l’Isle came from a family of French cartographers, though none were as acclaimed as he would become. He trained under his father from an early age and later studied mathematics and astronomy under Cassini. This combination of practical mapmaking experience and a deep scientific understanding of cartographic principles allowed De l’Isle to become one of the most significant figures in early 18th-century cartography.

De l’Isle established his firm in his twenties, issuing his first atlas in 1700. Two years later, he became a member of the Royal Academy and moved his firm to the Quai de Horloge, a center for printing and mapmaking in Paris. In the following years, Guillaume De L’Isle would produce some of his repertoire’s most iconic and essential maps. In 1718, he was appointed Royal Geographer to King Louis XIV, a position which he maintained under Louis XV until his premature death in 1726.

Pieter SchenkPieter Schenk the Elder (1660-1711) was a Dutch printer and engraver who moved to Amsterdam in 1675. Some twenty years later, he managed to acquire map plates from the estate of mapmaker Johannes Janssonius. Using these as templates, Schenk began specializing in the engraving and printing of maps and prints.

During his most productive period, Schenk worked in multiple languages and published both in Amsterdam and Leipzig. He also supplied his materials to the English market through dealers in London. Upon his death in 1711, the business was split between Schenk’s three sons. While Peter the Younger continued the business in Leipzig, Leonard and Jan ran the Amsterdam outfit.

Condition Description

Good to very good. Some toning and discoloration in margins, especially top corners.

References

![[AMERICAN REVOLUTION] Boston, George Washington, Franklin, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NL-02090a_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)