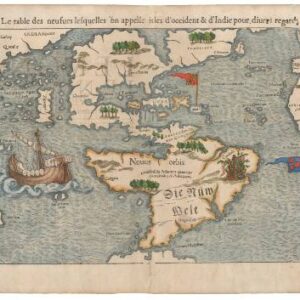

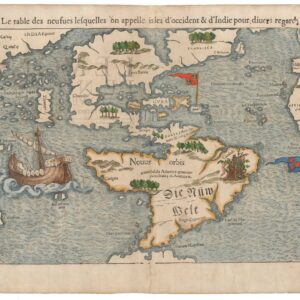

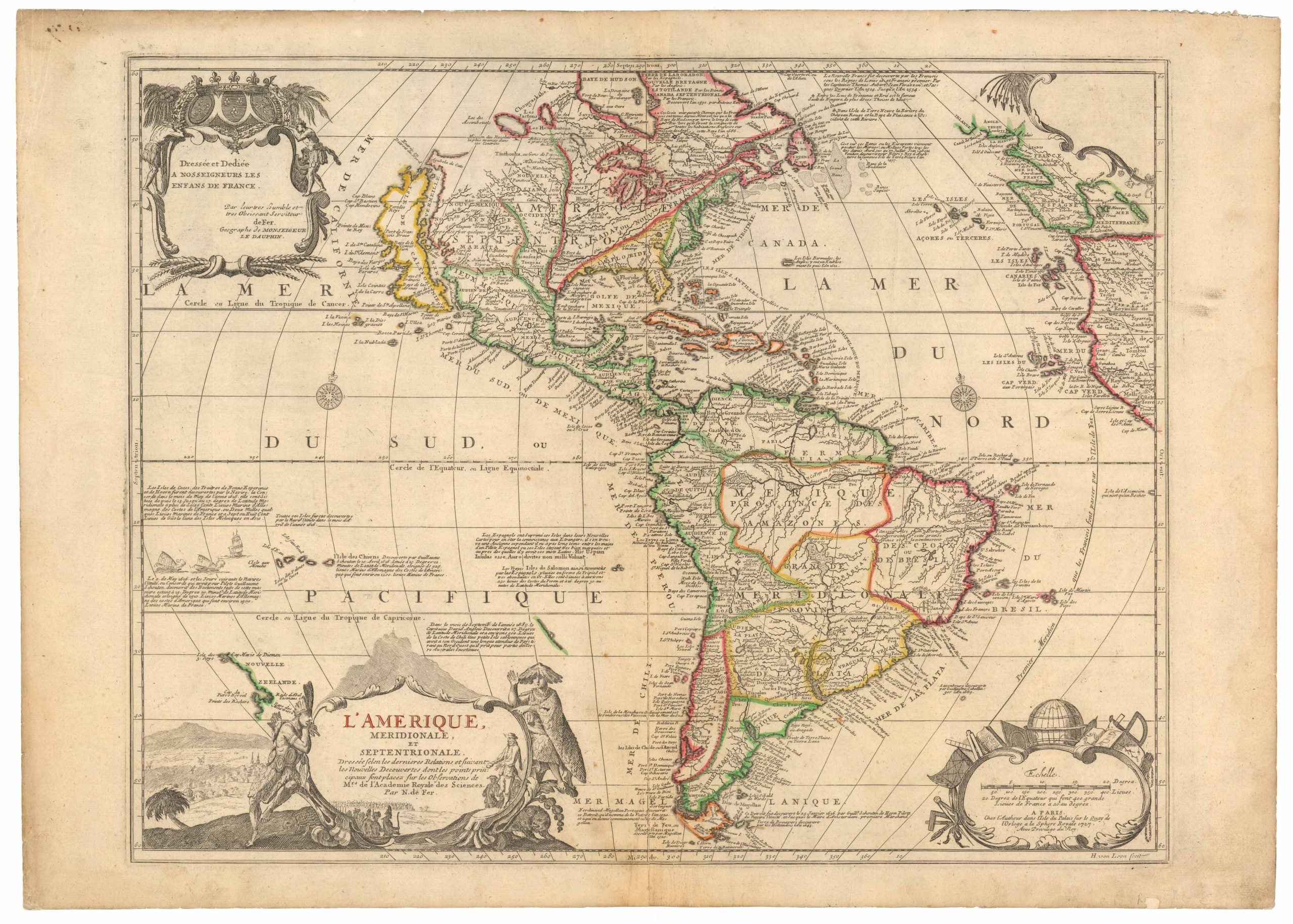

Sebastian Münster’s Iconic Map of the New World.

Die neüwe Inseln so hinder Hispanien gegen Orient bey dem land Indie ligen.

$6,500

1 in stock

Description

The First Printed Map of the American Continents in Their Entirety.

Münster’s map of the Americas is a work of firsts. It is the first printed map in history to depict the American continents in their entirety, the first map to apply the term “Mare Pacificum” as a place name, and one of the earliest European depictions of Japan and its associated archipelago (published three years before the first European ships reached Japan). For decades, this was the most widely circulated and influential map of the New World. It held unparalleled dominance for thirty years, only gradually being replaced after Abraham Ortelius published his seminal map of America in 1570. These characteristics make it one of the most collectible maps of the Americas today and an essential cornerstone of any serious collection.

A Paradigm-Setting Map

The most significant achievement of this map is its complete depiction of the Americas. While the outline is somewhat distorted, North and South America are clearly recognizable—a remarkable feat for a map published in 1540. North America’s division best exemplifies its early nature into two nearly separate landmasses. A large body of water bisects the continent, with the two halves labeled FRANCISCA and Terra Florida, respectively.

Another distinctive feature that sets Münster apart from his contemporaries is the absence of a landmass in the Pacific Northwest and the clear separation of America from Asia—an insight often attributed to Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1561 world map. The coastal mountain range, while tempting to associate with the Rocky Mountains, is more likely a cartographic embellishment. Similarly, Central America is rendered distorted, forming an elongated and exaggerated isthmus that connects to Guyana and northwestern Brazil. This depiction results in a flattened northwest region of South America and an oversized bay separating Central and South America.

Place Names and Geographic Understanding

Analyzing the place names helps us understand the distortions in the continents’ shapes. Münster’s toponymy provides insights into 16th-century European perceptions of the Americas.

- The northeastern landmass is labeled FRANCISCA, a tribute to King Francis I of France, who sponsored Giovanni da Verrazzano’s 1524 expedition. Verrazzano was the first European to survey the North American coastline from Florida to New Brunswick, including Narragansett Bay, New York Harbor, and New England. During his journey, he mistakenly reported a vast “Oriental Sea” (the Sea of Verrazzano) along the Outer Banks of North Carolina, which Münster incorporated into his map.

- C. Britorum marks the region explored by John Cabot (sailing under the English flag) and early fishing and whaling activities dating back to the late 15th century.

- Terra Florida appears on a printed map in this 1540 edition for the first time.

- Chamaho, a generic term, represents what would later become Mexico.

In contrast, the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico regions were better understood, resulting in a higher density of place names and more accurate representations.

- The larger islands, including Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico (“Sciani”), are clearly labeled.

- Jamaica, St. Paul, and Cozumel (“Conzumela”) also appear.

- A large Castilian banner marks Spain’s Caribbean possessions, reinforcing the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which divided the Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence.

- A Portuguese banner on Fernando de Noronha emphasizes Portugal’s claim to Brazil.

A notable error is labeling Iucatana as a sizeable western island, which reminds us how early this map was created. In Central America, Münster includes the name PARIAS, followed by the phrase “abundance auro & margaritas” (abundant in gold and pearls), referencing Columbus’s reports of a wealthy land south of Hispaniola.

South America’s Labels and Legends

South America’s labeling differs significantly from North America’s. The two most extensive inscriptions are Die Nüw Welt and Nouus Orbis, both meaning “The New World” (the former in German, the latter in Latin). Between them, a Latin text reads:

“Noua Insula Atlantica quam uocant Brasily & Americam”

(The new Atlantic island called Brazil and America).

Münster was not the first to name the New World “America”—that distinction belongs to Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map—but Münster’s map played a crucial role in popularizing the name, ensuring its permanence in cartography.

In western South America, Catigara appears on the coast of modern-day Peru. Originally described by Ptolemy as the southeasternmost city in the known world, Catigara was believed to be part of a landmass connecting Asia and Africa. When explorers disproved this theory, geographers shifted Catigara to South America, as Münster does here.

A legend in southwest South America reads Regio Gigantum, referencing the so-called Patagonian Giants. This myth originated from Magellan’s 1520 expedition, during which he claimed to have encountered giant natives along the Patagonian coast. Though Magellan’s original report was lost, his crew’s exaggerated tales ensured the legend’s survival in European cartography for centuries.

Magellan’s Influence on the Map

Magellan’s impact is even more pronounced in the map’s depiction of the Pacific Ocean. Among its many firsts, Münster’s map is the earliest printed map to label the Pacific Ocean “Mare Pacificum”. Magellan is further honored with Fretum Magaliani, the Magellan Strait, a name it retains today.

Though Münster compresses the Pacific’s width, he does so to include Japan (Zipangri), reflecting Marco Polo’s influence. The many islands surrounding Japan are labeled “Archipelagus 7448 insularũ,” referencing Polo’s claim of 7,448 islands, likely referring to the Philippines.

Artistic and Decorative Elements

Münster’s map includes vignettes of mountains and forests. The most dramatic scene appears in northeastern Brazil, where a large pyre with human body parts labeled “Canibali” illustrates the European perception of cannibalism in the New World.

A magnificently drawn caravel dominates the Pacific Ocean, symbolizing Magellan’s fleet. Of the five ships that set sail, only one—Victoria—returned, carrying just 18 survivors. Magellan himself was killed in the Philippines.

Publication information

Due to its iconic status, Münster’s America’s map was reissued for over a century in at least thirteen known states. This 1567 German edition of Cosmographia is the 11th state (Burden 12).

Cartographer(s):

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) was a cosmographer and professor of Hebrew who taught at Tübingen, Heidelberg, and Basel. He settled in Basel in 1529 and died there, of the plague, in 1552. Münster was a networking specialist and stood at the center of a large network of scholars from whom he obtained geographic descriptions, maps, and directions.

As a young man, Münster joined the Franciscan order, in which he became a priest. He studied geography at Tübingen, graduating in 1518. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Basel for the first time, where he published a Hebrew grammar, one of the first books in Hebrew published in Germany. In 1521, Münster moved to Heidelberg, where he continued to publish Hebrew texts and the first German books in Aramaic. After converting to Protestantism in 1529, he took over the chair of Hebrew at Basel, where he published his main Hebrew work, a two-volume Old Testament with a Latin translation.

Münster published his first known map, a map of Germany, in 1525. Three years later, he released a treatise on sundials. But it would not be until 1540 that he published his first cartographic tour de force: the Geographia universalis vetus et nova, an updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. In addition to the Ptolemaic maps, Münster added 21 modern maps. Among Münster’s innovations was the inclusion of map for each continent, a concept that would influence Abraham Ortelius and other early atlas makers in the decades to come. The Geographia was reprinted in 1542, 1545, and 1552.

Münster’s masterpiece was nevertheless his Cosmographia universalis. First published in 1544, the book was reissued in at least 35 editions by 1628. It was the first German-language description of the world and contained 471 woodcuts and 26 maps over six volumes. The Cosmographia was widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many of its maps were adopted and modified over time, making Münster an influential cornerstone of geographical thought for generations.

Condition Description

Hand color. Visible repairs, as seen on the image. Overall nice.

References