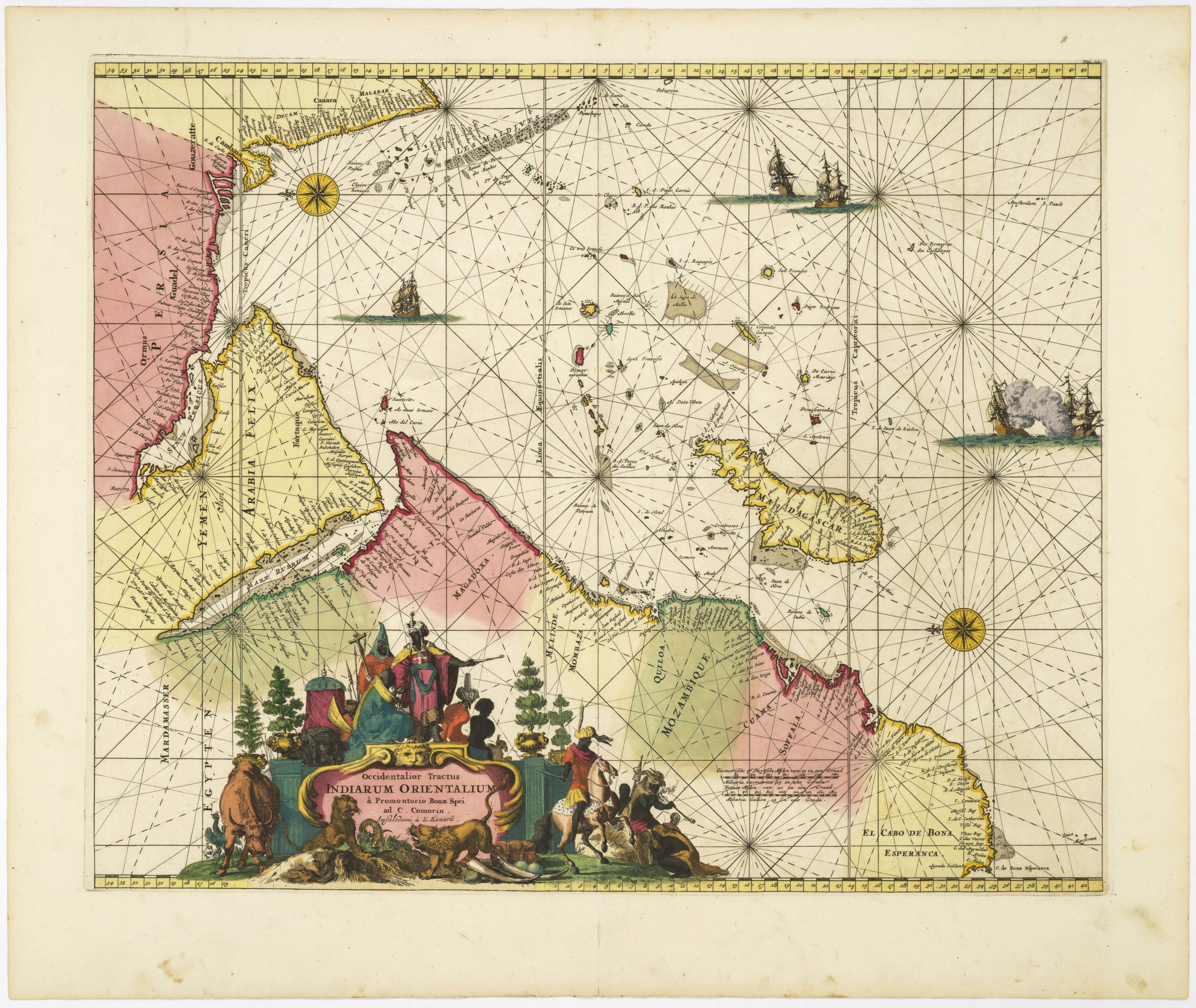

Ortelius’s fine map of Morocco, with an inset of Pigaffetta’s Kingdom of Congo.

Fessae, et Marocchi Regna Africae Celeberr.

$700

1 in stock

Description

The present example of Abraham Ortelius’s celebrated map of Morocco was issued in 1595 as part of the print’s first run and provides a detailed overview of the Wattasid Kingdom based in Fez. The country is bound to the north and west by sea, including the famed Strait of Gibraltar, gateway to the Mediterranean, and to the south, one finds the endless shifting sands of the Sahara. The shoreline is rendered with incredible precision, drawing heavily on the Portuguese pilot charts of the African shoreline and repeated Portuguese attempts to establish a permanent foothold in North Africa.

Renowned Flemish engraver Frans Hogenberg carved the map, depicting headlands, bays, estuaries, and particularly the Strait of Gibraltar with impeccable clarity. Key settlements like Tangier, Ceuta, Rabat, Salé, and Azemmour have all been clearly labelled along the coast. The degree of detail continues as we move inland, declining only beyond the natural barrier of the Atlas Mountains in the south. The twin royal cities of Fez and Marrakech (Marruecos) are correctly plotted and depicted as small bird’s‐eye vignettes, showing their impressive walls, towers and mosques in remarkable detail. Morocco’s third royal city, Meknés (Mequinez), was only developed as such in the late 17th century, so it has not been included in Ortelius’s masterful composition.

In the Atlantic, we find several vital clusters of islands, claimed by Iberian kingdoms. Most of Africa’s Atlantic islands – as well as the Azores and Madeira – had been claimed by Portugal during the 15th century. But in 1479, the Treaty of Alcáçovas saw Portuguese recognition of Castile’s sovereignty over the Canary Islands. In return, Castile recognized Portugal’s right to other Atlantic territories, like Madeira and the Azores, and, not least, exclusive rights to explore Africa south of the Canaries. The Canaries and Madeira are shown as archipelagos with topographic relief indicated by hachure. Sandbanks and shoals near the coast hint at navigational hazards, while the sea itself is populated by galleons and caravels, evoking the intense maritime traffic of the late sixteenth century. A large whale or sea monster – found between Morocco and the Canary Islands – hints at the perils of life at sea. Immediately north of this creature, a three‐masted carrack with billowing sails references the importance of intercontinental trade. In general, it is worth noting how each of the ships depicted is oriented explicitly west, embodying the spirit of exploration and referencing the discovery of the New World.

Ortelius drew upon several authoritative sources to compile this map. He adapted the coastal outlines from Giacomo Gastaldi’s Italian pilot chart, but integrated new information on ports and headlands provided by the Venetian cosmographer Livio Sanuto’s (c. 1520–1576) in his Geografia (1588). Inland, Ortelius retained the customary blank spaces found on early modern maps, filling them with a combination of real and generic mountain ranges and rivers (e.g., the Sebou/Cebu and Tensift/Rio Tancifer). Beyond the inland mountain ranges, the Saharan interior remains largely undefined, save for the long caravan route stretching from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. While this selective approach also reflects a lack of knowledge of the North African interior at this stage, it is also due to an explicit and deliberate emphasis on the nautical.

An important insight

Dominating the upper‐left quadrant is a large inset, Congi Regni Christiani, in Africa, Nova Descriptio. This constitutes a miniature map of the Kingdom of the Congo based on Filippo Pigafetta’s 1591 chart. Pigafetta, an Italian scholar and papal official, compiled his map from the eyewitness account of Duarte Lopes, a Portuguese trader who spent twelve years in the Congo hinterland. Ortelius’s inset preserves Pigafetta’s careful depiction of the Congo River (labeled Zaire), the kingdom’s six administrative provinces, and its principal settlements: San Salvador (present‐day M’banza‐Kongo) and the coastal trading hub Loango. Surrounding regions like Ndongo, Matamba, and Angola are delineated by rivers and mountain ranges. An essential aspect of Pigafetta’s map is how the region’s toponymy reflects spiritual and commercial ties between Congo and Lisbon. However, being an emissary of the Vatican and presenting Congo as a Christian realm governed by King Álvaro II, Pigafetta also underscores the Vatican’s influential role in the early colonisation of West Central Africa.

Attributes of a great atlas map

The map’s decorative program is characteristic of late sixteenth‐century atlases. In the lower right, an ornate strap-work cartouche frames the map’s title. This is flanked by sphinxes, putti bearing spears, and cornucopia baskets signalling tropical abundance. An elegant neatline frames the composition, lending formality to the fluid maritime scene.

On the verso, a Latin text summarizes Morocco’s history, economy, and political structure, including notes on the rise of the Alaouite sultans in Fez, the annual pilgrimage of caravans to Sijilmasa, and the Cinqueterre of corsair ports along the Barbary Coast. Also included are brief remarks on the Kingdom of the Congo, noting its conversion to Christianity, its governance under Portuguese patronage, and its wealth in ivory and enslaved people.

Ortelius’s 1595 map of Morocco, with its inset of Pigafetta’s map of the Kingdom of Congo, is a testament to the collaborative nature of sixteenth‐century cartography. By synthesizing Italian pilot charts, Portuguese voyage reports, and Vatican missionary surveys into a single, richly ornamented sheet, Ortelius offered European audiences an up-to-date insight into Africa’s enormity and cultural complexity.

Census

Abraham Ortelius did not issue this map of Morocco until 1595, some 20 years after the first edition of his famous atlas hit the streets. The present map, which is dated 1595 in the title cartouche, constitutes the first state of this seminal late addition. The plate was engraved by the renowned Flemish engraver and Ortelius’s long-standing collaborator, Frans Hogenberg. It was issued as part of the 1601 Latin edition of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, published by Christophe Plantin’s press in Antwerp.

Placed in the empty desert to the left of the title cartouche, the map bears Ortelius’s original imprint (Abrah. Ortelius. Cum Imp. Reg. & Brabantiae privilegio decennali.). Like the date itself, this imprint is only found on the first state of this map.

Cartographer(s):

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) was born in Antwerp to Flemish parents in 1527. After studying Greek, Latin, and mathematics, he and his sister set up shop as book dealers and a ‘painter of maps.’ In his heart, Ortelius was, nevertheless, first and foremost a historian. He believed geography was the ‘eye of history,’ which explains why he collected maps and historical documents with such passion. Ortelius traveled widely in pursuit of his interests, building contacts with mapmakers and literati all over the European continent.

Ortelius reached a turning point in his career in 1564 with the publication of a World Map in eight sheets, of which only a single copy survives. In 1570, he published a comprehensive collection of maps titled Theatrum orbis terrarum (Theatre of the World). The Theatrum is conventionally considered the first modern-style atlas. It was compiled by collecting maps and charts from colleagues across the continent, which Ortelius then had engraved in a uniform size and style. The engraver for most of the maps in Theatrum was none other than the famous Frans Hogenberg, who also served as the main engraver for the 16th-century urban atlas Civitates Orbis Terrarum, published with Georg Braun in 1572.

Hogenberg’s re-drawn and standardized maps formed the basis of the first atlas in history (even though it was Mercator who was the first to use the term a few decades later). Unlike many of his contemporaries, Ortelius noted his sources openly and in the first edition, acknowledged no less than eighty-seven different European cartographers. This ‘catalogus auctorum tabularum geographicum‘ is one of the major innovations of his atlas. The list of contributing mapmakers was kept up-to-date for decades after Ortelius’ death. In the first edition of 1570, this list included 87 names, whereas the posthumous edition of 1603 contained no less than 183 names.

While compiled by Abraham Ortelius in the manner described above, the Theatrum was first printed by Gielis Coppens van Diest, an Antwerp printer experienced with cosmographical books. Van Diest was succeeded by his son Anthonis in 1573, who in turn was followed by Gillis van den Rade, who printed the 1575 edition of Ortelius’ atlas. From 1579, Christoffel Plantin took over, and his successors continued to print Theatrum until Ortelius’ heirs sold the copperplates and the publication rights to Jan Baptist Vrients in 1601. In 1612, shortly after Vrients’s death, the copperplates passed to the Moretus brothers.

Condition Description

Fine; heavy centerfold.

References

Van den Broecke #177.