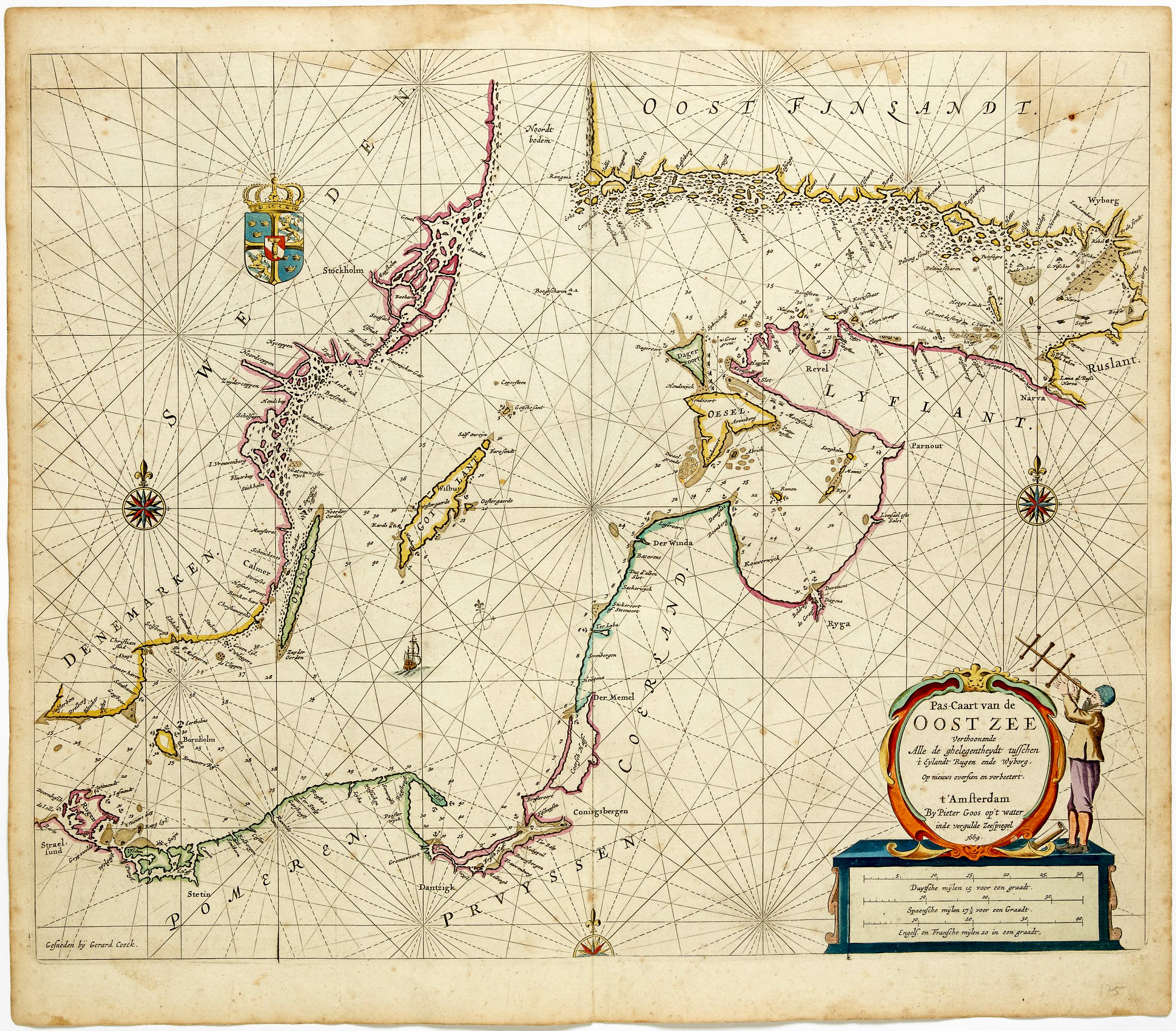

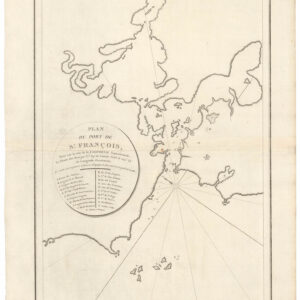

The earliest obtainable map of the Nicolò Zeno expedition to Frisland & Greenland in 1380.

Septentrionalium Partium Nova Tabula

Out of stock

Description

This map shows the Northern Atlantic. Iceland (Islanda) is near the center with Norway and Sweden to the east on this north-oriented map. However, there are also other islands that one would not see on a map today, including Frisland, Estotiland, and Icaria. Frisland is highly detailed, with over thirty place names. What are these islands and where did they come from?

The Zeno brothers and their voyage of 1380

The Zeno family was part of the Venetian elite; indeed, their family had controlled the monopoly of transport between Venice and the Holy Land during the Crusades. Nicolo Zeno set off in 1380 to England and Flanders; other evidence seems to corroborate this part of the voyage. At some point his ship was caught in a huge storm, blowing him off course and depositing him in the far North Atlantic. He and his crew were supposedly wrecked on a foreign shore, the island of Frislanda.

Thankfully, the shipwrecked Venetians were found by King of Frisland, Zichmi, who also ruled Porlanda, an island just south of Frisland. Zichmi was on a crusade to conquer his neighbors and Nicolo was happy to help him strategize. Nicolo wrote to his brother, Antonio, encouraging him to join him and, good navigator that he was, Antonio sailed for Frisland and arrived to help his brothers. Together, they led military campaigns against Zichmi’s enemies for fourteen years.

Their fights led the brothers to the surrounding islands, presumably enabling them to make their famous map. Zichmi attempted to take Islanda, but was rebuffed. Instead, he took the small islands to the east, which are labeled on this map. Zichmi built a fort on one of the islands, Bres, and he gave command of this stronghold to Nicolo. The latter did not stay long, instead sailing to Greenland, where he came upon St. Thomas, a monastery in Greenland with central heating. This too is marked on the map. Nicolo then returned to Frisland, where he died four years later, never to return to Venice.

Antonio, however, was still alive. His letter explains that he ran into a group of fishermen while on Frisland. These fisherman had been on a 25 year sojourn to Estotiland, which is peeking out of the western border of the map. Supposedly, Estotiland was a great civilization and Latin-speaking, while nearby Drogeo, to the south, was full of cannibals and beasts. Antonio, on Zichmi’s orders, sought these new lands, only to discover Icaria instead. The Icarians were not amenable to invasion, however, and Antonio led his men north to Engroneland, to the north. Zichmi was enthralled with this new place and explored inland. Antonio, however, returned to Frisland, abandoning the King. From there, Antonio sailed for his native Venice, where he died around 1403.

Publication and legacy

News of the discoveries and the first version of this map was published in 1558 by another Nicolo Zeno, a descendent of the navigator brothers. Nicolo the Younger published letters he had found in his family holdings, one from Nicolo to Antonio and another from Antonio to their other brother, Carlo, who served with distinction in the Venetian Navy. They were published under the title Dello Scoprimento dell’isole Frislanda, Eslanda, Engrouelanda, Estotilanda, & Icaria, fatto sotto il Polo Artico, da due Fratelli Zeni (On the Discovery of the Island of Frisland, Eslanda, Engroenland, Estotiland & Icaria, made by two Zen Brothers under the Arctic Pole) (Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1558).

At the time of publication, the account attracted little to no suspicion; it was no more and no less fantastic than most other voyage and travel accounts of the time. Girolamo Ruscelli (ca. 1504-1566) published this version of the Zeno map in 1561, only three years after it appeared in Zeno’s original work. Ruscelli was a Venetian publisher who also released an Italian translation of Ptolemy. Ruscelli had moved to Venice in 1549, where he became a prominent editor of travel writings and geography.

Ruscelli was not the only geographer to integrate the Zeno map into his work. Mercator used the map as a source for his 1569 world map and his later map of the North Pole. Ortelius used the Zeno islands in his map of the North Atlantic. Ramusio included them in his Delle Navigationo (1583), as did Hakluyt in his Divers Voyages (1582) and Principal Navigations (1600), and Purchas (with some reservation) in his Pilgrimes (1625). Frisland appeared on regional maps of the North Atlantic until the eighteenth century.

In the nineteenth century, when geography was popular as both a hobby and a scholarly discipline, the Zeno account and map came under scrutiny. Most famously, Frederick W. Lucas questioned the validity of the voyage in The Annals of the Voyages of the Brothers Nicolo and Antonio Zeno in the North Atlantic (1898). Lucas accused Nicolo the Younger of making the map up, using islands found on other maps and simply scattering them across the North Atlantic. He also accused Nicolo of trying to fabricate a Ventian claim to the New World that superseded the Genoan Columbus’ voyage. Other research has revealed that, when he was supposed to be fighting for Zichmi, Nicolo was in the service of Venice in Greece and Venice in the 1390s. He is known to have drafted a will in 1400 and died—in Venice, not Frisland—in 1402.

Scholars still enjoy trying to assign the Zeno islands to real geographic features. For example, Frisland is thought to be part of Iceland, while Esland is supposed to be the Shetlands. Some still believe the Zenos to have sailed to these lands. Most, however, view the voyage and the map as a reminder of the folly and fancy (and fun) of early travel literature and cartography. Whatever the truth, the Zeno map and its islands are one of the most enduring mysteries in the history of cartography and the Ruscelli map sped the story’s exposure in Europe.

Cartographer(s):

Girolamo Ruscelli (1518–1566) was an Italian mathematician, polygraph, and cartographer active in Italy during the early 16th century. He was born around 1518 in Viterbo to a family of minor nobility and humble origins. Throughout his life, Ruscelli moved around, living all over Italy. He started in Aquilea, but his work soon drew him to more important centers of learning. He moved first to Padua, and around 1540, he settled in Rome, where he founded his Accademia dello Sdegno. Around 1545, Ruscelli left Rome for Naples, and in 1548 he finally settled in the city that would make him most famous, Venice.

While posterity primarily remembers Ruscelli as one of the most important cartographers of the Venice School, his primary source of income came from publishing – both his works and copying the work of others. While he wrote on a broad range of subjects himself, the works plagiarised from others were often published by his partner, Plinio Pietrasanta. This lucrative relationship lasted until 1555 when Ruscelli was arrested and tried by the Inquisition for re-publishing a satirical poem by Pietrasanta without his formal permission. Any confrontation with the Inquisition was unpleasant enough, but Ruscelli may have been particularly susceptible to pressure because his wife’s family entertained Protestant sympathies. His brother-in-law was burned at the stake in Rome some years later.

The relationship with Pietrasanta had nevertheless soured, and the publishing firm was soon closed. Instead, Ruscelli partnered up with another Venetian publisher, Vincenzo Valgrisi. It was with Valgrisi that Ruscelli published his famous Ptolemaic Geografia in 1561. This atlas contained sixty-nine engraved maps sporting the latest ideas in Italian cartography. Despite containing some of the latest cutting-edge ideas about the world’s composition, Ruscelli’s atlas also drew heavily on earlier works. Forty of the 69 maps in Ruscelli’s atlas were copied almost directly from Giacomo Gastaldi’s Geografia from 1548.

Despite Ruscelli’s fame as a cartographer, he also achieved considerable recognition under his pseudonym Alessio Piemontese. His greatest success in this regard came the same year as his arrest (1555), with the publication of De Secreti del Alessio Piemontese. In this book of alchemy, Ruscelli reveals himself as a true Renaissance man, dabbling proficiently in multiple disciplines at the same time. His ‘Secrets‘ contained instructions on how to make everything from alchemical compounds and medicines to cosmetics and dyes. The work was so popular that it was re-issued numerous times over the next two centuries, and translated into French, English, German, Latin, Dutch, Spanish, Polish, and even Danish.

Condition Description

Fine; dark impression.

References

Tooley, revised edition Q-Z, 87. Edward Brooke-Hitching, The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps (London: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 242-4. For an example of one who believes in the Zeno map, see William Herbert Hobbs, “Zeno and the Cartography of Greenland,” Imago Mundi VI (1949): 15-19.