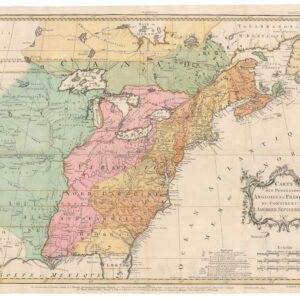

Colton’s seminal 1849 map of the United States: an encapsulation of the pivotal political developments of the 1840s.

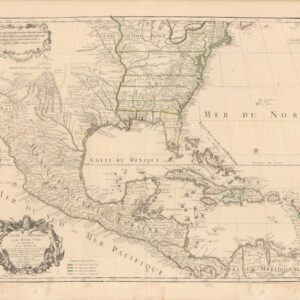

Map of the United States of America, the British Provinces, Mexico, the West Indies, and Central America: with part of New Granada and Venezuela.

Out of stock

Description

With extended Texas borders shown in multiple configurations.

This first edition of Colton’s gorgeous 1849 map of the United States shows the country on the coattails of the war with Mexico and at the dawn of the California Gold Rush. It is a quintessentially American map that embodies some of the most important developments in U.S. history.

In addition to its historical importance, Colton’s map constitutes an aesthetic icon in the repertoire of 19th-century cartography. It is characteristic of the highly decorative style of its designer and main engraver, John M. Atwood. While Atwood undoubtedly engraved the map itself, he is also likely to have been the man who conceptualized the whole. To support his vision, he was competently assisted by W.S. Barnard, who designed and engraved the ornamental grape vine border, as well as the many pictorial vignettes that this map has been endowed with throughout.

Most importantly, the map arrived on the cusp of the Compromise of 1850, which dramatically altered America’s internal borders. This makes the map’s visualization of the American West exciting for a number of reasons, especially:

- The borders of Texas are seen in their post-Mexican-American War form. Two possibilities are offered, one in red-pink ink and the other by means of dashed lines. The latter extends north along the Guadalupe Mountains all the way up to modern-day Wyoming. Both configurations include Santa Fe, which Texas coveted but lost in the Compromise of 1850.

- The huge territory of Mexican cessation to the west of Texas is still unorganized. Simply called ‘Upper or New California,’ in the following year this would become New Mexico Territory (eventually split into New Mexico and Arizona), Utah Territory (eventually split into Utah and Nevada), and the state of California.

The New State of Texas

In the period leading up to the creation of this extraordinary map, American immigrants in Texas fermented a revolution that saw Texas’ secession from Mexico and the creation of an independent Republic of Texas (1835-45), and subsequently, the annexation of that republic to the United States (1845). While Mexico protested the annexation, the dispute soon centered on Texas’ western border. The Mexican claim saw the border between Texas and Mexico defined by the Colorado, Guadalupe, and Nueces Rivers. In contrast, the American view was that the Rio Grande (aka Rio del Norte) constituted the legitimate border.

The dispute spiraled into an all-out war between Mexico and the United States within three years. After more than a year of fighting, the conflict was resolved in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). The result was an enormous American victory, for not only did the treaty define the Rio Grande as Texas’ western border, but it also ceded more than 50% of Mexico’s territory to the United States, including California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado.

Colton’s map depicts the borders of the United States as consolidated in this manner. It is, in effect, a form of cartographic propaganda cementing the recent massive expansion of U.S. territory. Among the most notable aspects is that the country now stretches from coast to coast, itself a stunning achievement for the young democracy.

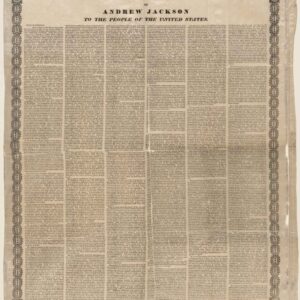

Looking more closely at Texas, we note how the mapmaker depicts it to its fullest extent and explicitly as an American state. Nevertheless, Colton has also opted to show other interpretations of where the Texas border could run and claims within Texas. These include conflicting configurations that were hotly debated before and during the war with Mexico. For example, highlighting the border along the Nueces River was among the firmest Mexican claims. In many ways, the final configuration of Texas was still an active debate when this map was published, as it only was in the Compromise of 1850 that the final border terms were agreed upon.

In other words, the particular composition of this map should not be perceived as indecisiveness on Colton or Atwood’s part. Quite the contrary, the mapmaker is adamant about Texas’ and the rest of the new United States’ territorial extent. The conflict that led to these new borders was so fresh and its origins so localized in Texas that Colton felt it prudent to supply his buyers with the necessary background to underscore the current vision and reality. Colton would ultimately be proven correct in his prediction that these were now the new formal borders of the United States. The land grab first defined by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and later cemented in the Compromise of 1850 would remain the United States border until modern times.

California and the impending Gold Rush

Another exciting element worth taking a closer look at is the new state of California, which within a few years of joining the United States would become one of the most populated and industrious in the nation. As stated, Upper California was ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February of 1848. Later that year, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, igniting the California Gold Rush.

Colton published this map that same year. Thus, while California’s geography is generally quite simple, ambition is evident. Colton has made an effort to include as much pertinent information on the gold fields of California as a map of this scale allows. It includes New Helvetia, the settlement founded by Swiss emigrant John Sutter at the convergence of the Sacramento River and one of its tributaries. Within a year of two of this map’s publication, this original settlement would be entirely supplanted by the new capital of Sacramento. Arched above New Helvetia, almost as if crowning the toponym, the map states ‘GOLD REGION’.

Other than locations associated very directly with the California Gold Rush, it is evident that very little is known about the interior at this stage. John C. Fremont’s famous expeditions into the Californian wilderness during the 1840s are noted in the form of the Humboldt River, and the notation of his route through the Sierra Nevada foothills and onto Utah on the map. However, his expeditions’ actual details and results have yet to make it fully onto this first edition of Colton’s map. There are so few details along the Sacramento River and its tributaries, but the coastal plain is more detailed. The Great Basin is virtually void of any geographic information at all. In the second edition of this map issued later the same year, these omissions were remedied and updated based on the surveys of Fremont and other California pioneers.

Alternative sources on the region were also drawn upon to compensate for the lack of proper geographic knowledge. These include the famous German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s interpretations of a northern source for the Aztecs, which on Colton’s map is placed on the Colorado River, just east of the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The label reads: ‘Supposed Residence of the Aztecs in the 12th century.‘ Another instance of a somewhat esoteric source informing this map is found across the Great Basin, where Upper California borders Texas. We find a label for the’ Ruins of Gran Quivira’ in the hills east of the more densely labeled Rio Grande Valley. Coronado and his conquistadors first plundered these Ancestral Puebloan cities in the 16th century.

The ancient ruins of this area became associated with the apocryphal legends of Cibola and the Seven Cities of Gold, drawing countless soldiers of fortune to the region. While the toponyms associated with this mythology continued to figure on maps for centuries after Coronado, it is quite surprising to find them on a meticulous and modern work such as this. Its presence reveals how obscure these large tracts of land remained to most people.

A balance of functionalism and aesthetics

As noted in the introduction, this map is both a cartographic and an aesthetic tour-de-force. While Atwood and Barnard’s stylistic genius is evident throughout, the above explanation hopefully underscored some of the cartographic achievements embedded in this great map. This juxtaposition of aesthetics and functionality is worth exploring further. It adds a beautiful layering to the visual expression and constitutes a distinctly mid-19th-century stylistic development that positions this map firmly within the broader repertoire 19th century American mapping.

For dramatic visual effect, we may begin with the electrifying cartouche in the Atlantic above the map’s title. The composition shows that all-American symbol, the bald eagle, crested on a shield embossed in the stars and stripes. Different trade goods and navigation instruments surround the leitmotif, all set against the backdrop of a bustling American port. This evocative imagery continues in the classical grape-vine border, which includes twelve finely engraved vignettes of important places or prototypical American activities.

The corners of the border are occupied by four larger images, whereas each side contains two smaller scenes ensconced within the leafy arabesque. Moving clockwise from the top left, the following scenes are included: salmon fishing at Willamette Falls, Oregon; Astor’s fur trading outpost in Oregon; Lake Saratoga in New York; the Connecticut River Valley as seen from Mount Holyoke; Bunker Hill Monument in Boston; the Washington Monument in New York City; the Capitol in Washington D.C.; ships entering a port; Mexicans catching wild cattle; the cathedral of Mexico City; the Pulaski Monument in Savanna, Georgia; and Baltimore’s Battle Monument.

To this impressive set of primarily national views can be added a substantial inset in the lower left corner, which depicts the Atlantic Ocean and the many Trans-Atlantic shipping and passenger lines crossing it. The routes include the famous New York – Boston – Halifax – Liverpool run, as well as more obscure routes such as the one between Cuba and Madeira. As in the larger map, the inset has been enriched with finely engraved little vignettes of steam- and sail ships plowing the ocean. While these vignettes add to the decorative element of the map, they are also functional in that they represent concrete information about how to get to and from the United States. A similar focus on mobility and connectivity is also found within the country, where multiple overland routes related to Westward Migration have been meticulously plotted on the map. These include the Oregon Trail and the Santa Fe Route, which run from Westport Landing in Missouri. Other routes include those taken by military expeditions, particularly of historical figures like General Kearney, John C. Fremont, and General Wool.

Final remarks

Colton’s 1849 map is truly a product of emerging American modernity in that it is designed as a layered and constructed landscape that serves multiple purposes simultaneously. There is no dichotomy between the beauty of the composition, the political declaration of the new territorial divisions, and the strictly functional aspects of depicting routes, borders, and critical physiographic features. Here all of these contradicting elements merge into an elegant whole that sets it apart from its contemporaries as one of the truly great American maps.

Census

The Colton Firm issued two distinct states of this map in the same year (1849). The two states are easy to distinguish based on their geography and toponymy in the West – especially those parts that had come under the United States following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

The need for a second edition was that too much new information had become publicly available for Colton’s original issue to remain cutting edge. The real driver behind the second edition was the anticipation of the Compromise of 1850, which pushed back the border of Texas a little in Mexico’s favor. Equally essential drivers were the incorporation of details from the explorations of Fremont and the latest information pertaining to the discovery of gold.

While both editions constitute incredible feats of cartography, the consensus is generally that the first edition is the more important due to its larger format and the fine representation of more short-lived cartographic realities. It has consequently become one of the most desirable mid-19th-century American maps on the market.

Examples of the first edition of Colton’s map can be found in the Library of Congress, the Leventhal Map Center of Boston Public Library (call no. G3300 1849 .C65), and in the Map Division of the New York Public Library (01-5133), to name a few. Institutional listings are noted in the OCLC under call nos. 5758282; 494437547; 144230191; and 244676706.

Cartographer(s):

The Colton Mapmaking Company was a prominent family firm of cartographic printers, who in the nineteenth century were leaders in the American map trade. Its founder, Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800-1893), was a Massachusetts native who in 1830 moved to New York City and slowly began setting up his publishing business, which in the beginning drew heavily on licensing maps by established engravers such as David H. Burr, Samuel Stiles & Company, and later Stiles, Sherman & Smith. Smith was a charter member of the American Geographical and Statistical Society, as was John Disturnell. This connection would later benefit Colton, in that it helped him to acquire the rights to several important maps.

By the 1840s, the Colton firm were producing their own maps. They produced anything the markets desired, from massive and impressive wall-maps to pockets guides, folding maps, immigrant guides, and atlases. One of the things that set the Colton company aside from many of its contemporaries in terms of quality, was the insistence that only steel plate engravings be used for Colton maps. These created much more well-defined print lines, allowing even minute features and labels to stand out clearly. By 1850, the Colton firm was one of the primary publishers of guidebooks, immigration itineraries, and railroad maps in America.

In the 1850s, Colton’s two sons, George Woolworth and Charles B., were brought on board to the firm. This inaugurated a process of expansion in which the company began taking international commissions and producing wholly independent maps and charts. From 1850 to the early 1890s, they also published several school atlases and pocket maps. The firm continued until the late 1890s, when it merged with a competitor and then ceased to trade under the name Colton.

Condition Description

Very good. Light foxing.

References

The map is prominently listed in the third volume of Carl I. Wheat's seminal study Mapping the Transmississippi West 1540-1861 (no. 591), published by the Institute of Historical Cartography in San Francisco.