The Hancock Automobile and Motorcycle Book: the first California Road Atlas for motorists.

The Hancock Automobile and Motorcycle Road Book

Out of stock

Description

This extremely rare road atlas from 1907 captures California at the dawn of motorized transport and is probably the very first California example of a map-book designed for motorists.

This is an absolute rarity and in many ways one of the most unique California-related items that Neatline has had the pleasure of offering. What we have here is presumably the first California Road Atlas meant specifically for motorists. The timing of its publication in 1907 is absolutely crucial too, as California underwent an automobile revolution during the 1910s. In the dedicated section below, we delve deeper into the historical context in which this amazing book appeared, but for now let us take a closer look at the item itself.

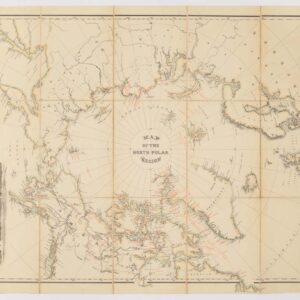

The highlight of the book are its two folding maps, which in unison provide users with an overview of the most of the state. The larger map depicts northern California, centering on the metropolis of San Francisco, but encompassing the entire region, from Sonoma in the north to Monterrey and Tulare Lake in the south. County lines are clearly delineated, just as the maps show all of the major roads and what cities and towns they connect. The second map shows southern California and extends roughly from Fresno in the north (where the other map stopped), to Los Angeles in the south. The maps are in other words two halves of a whole, and the red lines that denote the highways best suited for motorized traffic, extend beyond the limits of both maps to ensure a clear conceptual linkage between the two. The fact that the road atlas is focused not just on San Francisco and the north hints at the rise southern California would experience in the ensuing decade. Places like Los Angeles and San Diego were loci of important developments that would come to define the new century.

These were early days in the development of Los Angeles, far from the metropolis she would become. A number of isolated roads connected Los Angeles to the surrounding towns at the time, and only single road connected Pasadena, Los Angeles, and Santa Monica. At this time, the only highway that connected the LA to the rest of California was the northern turnpike that entered the city through the Hollywood Hills.

All of this would soon change dramatically, of course. But sadly, much of the growth that characterized Los Angeles in the first decades of the 20th century came as a direct consequence of the calamitous earthquake and fires that destroyed large parts of San Francisco the year before this book was published. While shock and devastation haunted San Francisco in 1907, she was still the fairest, largest, and economically most important city in California when this atlas was issued. Nevertheless, the urban landscape of San Francisco was in a state of flux following the destruction caused by the earthquake.

In 1907, the shift from San Francisco in the north to Los Angeles in the south may have been in the cards, but had not yet crystallized as an obvious pattern. Likewise, it is clear from this and other early California roads atlases that for now focus remained on San Francisco. This is echoed in the title page of Hancock’s book, which sports an almost full page map of the road networks around the southern Bay Area.

In addition to the maps, the Hancock Automobile and Motorcycle Book includes other content also worthy of attention. There is, for example, a distance index that defines the distances between fix points on given routes. These include San Francisco to San Jose; San Jose to Santa Cruz; San Francisco to Pescadero (with a return through Redwood City); San Francisco to Crystal Springs; and Oakland to San Jose. The road book’s maps are interspersed with an array of full page advertisements for anything that might be of interest to motorists. There are adverts for cars and brokers, as well as for the equipment and dress needed to look the part. We also find notes from insurers, invitations to join automobile clubs and associations, and even advertisements for tires, cleansers, and brake lubricants.

All in all, this wonderful little road atlas not only encapsulates what it meant to be an early motorist and car owner in sunny California, but also what traveling around the state would have been like in 1907. It harkens the massive change to come and is a poignant reminder of just how untamed and wild California still was just a century ago.

Census

We have already noted that this atlas is extremely rare and presumably the first of its kind. A second edition of Hancock’s Automobile and Motorcycle Book was published in 1909. Copies of this exits in the Map Collection of David Rumsey (no. 2728.000).

The OCLC notes copies, one in the California Historical Society, and one in the Huntington Library. It is not clear from the OCLC listing whether either of these copies constitute the 1907 original issue of Hancock’s book.

Context is everything

The history of automobiles and motorized vehicles in California begins at the very end of the 19th century. In many ways, it denotes the end of one era – early industrialization and urbanization – and the beginning of another. We do not know exactly when the first ever motorized vehicle was used in California, but the first American motor-car to appear in public in California ventured on to the streets of Los Angeles in the early morning hours of Sunday May 30th, 1897. The car in question was a four-cylinder, gasoline-powered carriage built by J. Philip Erie and S.D. Sturgis. In an early PR-stunt, Erie & Sturgis’ vehicle was meant to complete a trial run from Los Angeles to San Bernardino as its first public appearance. The engineers were nevertheless eager to test it in real-life conditions and thus drove it on to streets of Los Angeles some days before the trial run. The event caused headlines and helped ensure that by the late 1890s, California had been struck by the same automobile fever that had engulfed the East Coast in preceding years.

Motorism developed quickly from this point. In 1900, a group of enthusiasts formed the first official motor club when they founded the Automobile Club of Southern California. Only five years after that, more than 6500 motorized vehicles had been formally registered in California. The rapid development and contagious enthusiasm meant that the infrastructure could not be upgraded fast enough to accommodate the rising number of motorized vehicles. Many of the roads between towns and cities throughout California remained unpaved dirt roads meant for carriages and wagons, not cars and motorcycles. Up until this point, traveling had been a largely functional pastime; something with an explicit purpose and the possibility of planning in advance. Nobody foresaw that it would suddenly become a thing to just drive into the blue without any particular destination. The lag in infrastructure and the dramatic increase in cars also made motorized travel precarious, so motor clubs and automobile associations responded to the situation by putting up new and improved road signs and demarcating the best routes for cars to take. Our evocative road atlas plays into exactly that dynamic.

As interest increased and production was streamlined, cars gradually became more accessible to a wider public. In 1908, Henry Ford introduced the iconic Model T, which was a reliable and affordable car that was easy to drive. This meant that for the average American family, car ownership now was within reach, catapulting sales as a result. Ford’s incredible success changed the market, and despite being issued in 1909, the year after the Model T, it is clear from the diversified advertising content that when this atlas was compiled, this success was still in tis infancy. The timing also allows us to garner just how widely distributed American car manufacture was prior to Ford’s cornering of the market.

With the expansion of the driving class, the demand for road maps also soared. The Automobile Club of Southern California started issuing road maps around 1906, and by 1912 these had developed into the famous strip maps (a set of sliced map pages that follow a particular route). Our atlas was produced in the middle of this experimental and innovative period of mapping for American motorists. It was issued before the California Highway Act of 1910, which issued 18 million dollars in bonds dedicated to highway construction and renovation. This was arguably the most important piece of legislation related to motorized traffic in California, and set in motion a process of terrestrial infrastructure improvements that changed the state forever. The money was distributed to counties throughout the state, with each city and county competing to win funding for their particular projects. Despite being a massive amount at the time, it soon became clear that even 18 million would not suffice to provide California with the roads that it now urgently needed.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Excellent.

References

OCLC 84282861 & 58932314. Stanford Pub list no.: 2728.000.