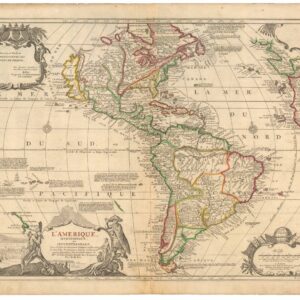

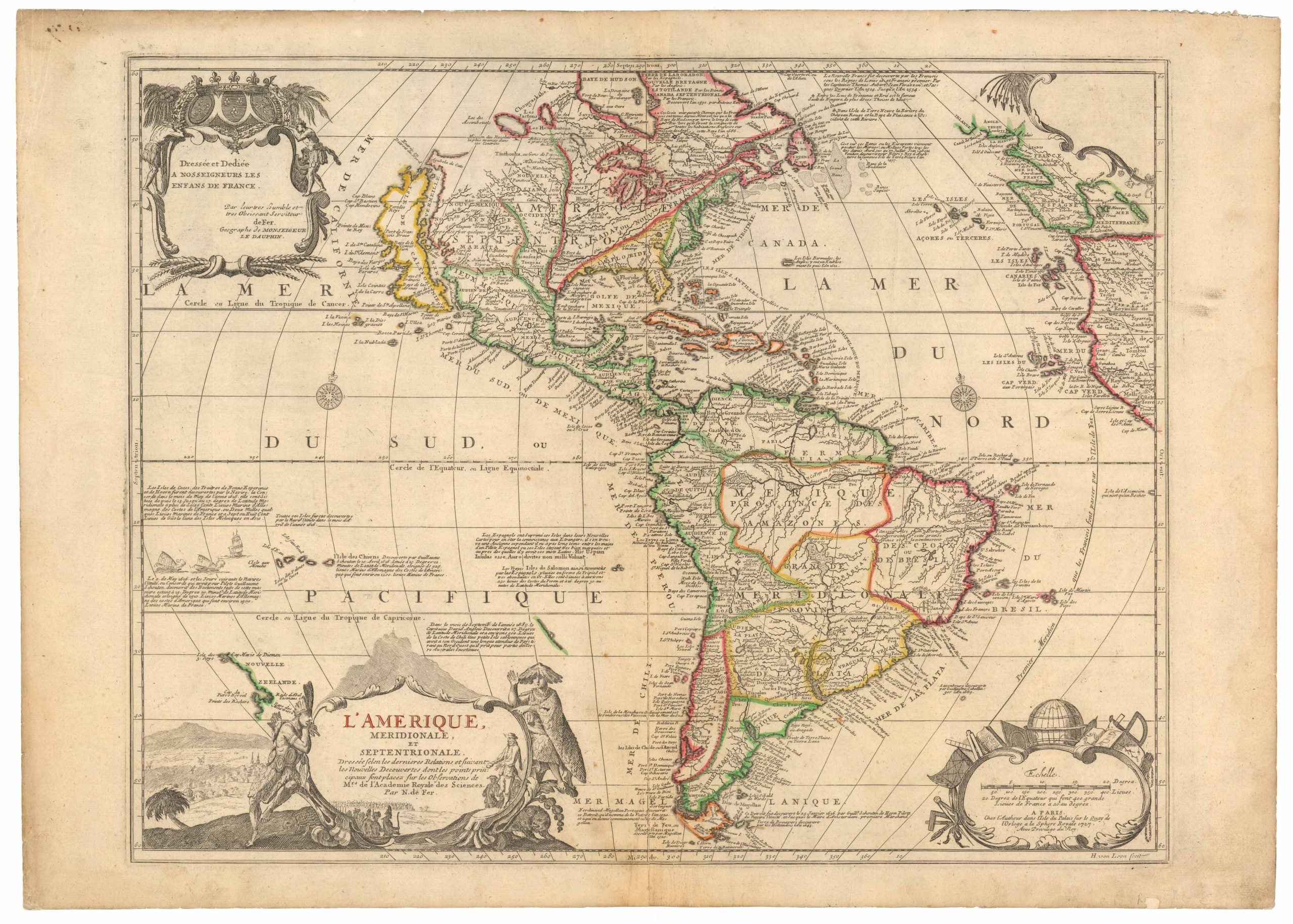

De Wit’s magnificent chart of the still partly obscure American continents.

Novissima et Accuratissima Totius Americae Descriptio.

Out of stock

Description

Celebrated as an important development in the Dutch mapping of the Americas, this circa 1680 map by Frederick de Wit carries all the hallmarks of a great 17th-century chart: from elaborately decorated cartouches to visual depictions of the great wilderness that characterized these young continents.

Most of America’s northwestern plains remain a largely unexplored Terra Incognita, complete with fur-bearing games such as wolverines, bears, and foxes. The Pacific Northwest is entirely absent from the chart.

De Wit had produced his first American chart in 1660 and a second more monumental wall map in 1672, but both of these were characterized by a paucity of credible geographical information. It is almost as if De Wit was aware of his wall map’s shortcomings because not long after he had published it, he began working on this much more accurate and comprehensive chart. While this new version clearly builds on his previous American charts, it was also informed by Guillaume Sanson’s 1669 map of North America, which provided much of the latest reliable information – especially in the French territories. The discrepancies between his own American charts and Sanson’s work seems to have motivated De Wit to produce something even better. It is likely that it was this competitive drive that lead to this new and spectacular chart.

De Wit’s 1675 chart included a number of important new additions, the most important of which undoubtedly was the inclusion of all five of the Great Lakes in the Midwest: Lac Superieur (Lake Superior), Lac des Puans (Lake Michigan), Mare Dulce (Lake Huron), Lac Erie (Lake Erie), and L. de S. Louis (Lake Ontario). However, the western coast of Hudson Bay has also been significantly updated, as have political demarcations in North American. The latter is emphasized both by extensive labeling, but more importantly by means of highly distinct regional colorations in the original green, pink, and orange colors.

California as an Island

Another important feature of this map is that California is depicted as an island. This cartographic enigma, which is celebrated by many collectors, began in earnest around the 1620s when maps of North America suddenly began depicting an Insular California. The notion developed following early Spanish expeditions up the Pacific coast. In particular, the writings of a Carmelite friar, Antonio de la Ascension, seem to have promulgated the idea among Spanish mariners and cartographers, and from here it soon spread to the formerly Spanish domain of the Netherlands. Throughout Europe, the competitive cartographic markets hungered for fresh information on the new world, and often ideas would be incorporated without much critical verification. It was all about being first.

The California-as-an-island idea had thus been well established by the time De Wit compiled his charts. Important predecessors such as Hendrik Hondius, Nicolas Sanson, and John Speed had all been taken in by the notion and included it prominently in their charts. It was, in other words, neither strange nor out of place for De Wit to follow in this tradition. In many ways, this De Wit map represents a unique point in time in which the geographic myth had transcended into cartographic reality, and before it was first debunked by Father Kino, who traveled the Pacific coast and verified the peninsular nature of California himself. Kino published his observations in Paris in 1705, but the insular depiction continued well into the 18th century.

South America and the Legend of El Dorado

Even though South America seems to have been portrayed in full, there are still many aspects of its depiction that reveal it to be riddled with speculation and mythology. Highly important is of course the depiction of Cape Horn, as this was the only known route from the Atlantic to the Pacific at the time. While the Straits of Magellan and the Straits of Le Maire (Lemair) have been depicted fairly accurately, the map also includes a Strait of the Brouwers, which runs between the known State Island (Staten Lant) and a second undefined island to the east, which does not exist.

Like in North America, De Wit has used the open swathes of unknown wilderness for artistic depictions that were meant to instill wonderment and excite the imagination. We have mentioned the wild mammals on the Great Plains and similar use is made of the Amazon, where indigenous villages and combat scenes fill up the uncharted space. While still a largely unexplored region at the time, the Amazon includes an extensive network of rivers extending from the unknown interior to their various deltas on the coast. As waterways constituted the only transportation infrastructure through the dense vegetation, it is no surprise that rivers were the most accurately marked out physiographic features on the map. Indeed, prior to the Portuguese and English pushing them out of the region, the Dutch had entertained huge imperial ambitions for Brazil.

An interesting inclusion, albeit hardly unique for the time, is the depiction of Lake Parime in modern Guyana. This mysterious lake has been repeatedly associated with the legend of Eldorado; a city of gold supposedly located on its shores. While there exists no historical or archaeological data to corroborate that such a place ever existed, the myth has been both long-lived and extremely tenacious. Obviously, the notion must have sprung from the immense wealth that the conquistadors brought back from the New World. The opportunities that this new and vast territory afforded attracted many adventurers and opportunists, to whom history’s judgment has not been very kind.

The notion was nevertheless pervasive. So much so that expeditions continued to be launched well into the 20th century (e.g. Colonel Percy Fawcett). The most infamous expeditions to find the mystical city of gold were perhaps those led by Sir Walter Raleigh, the close confidant, and advisor of Queen Elizabeth I. Raleigh made several attempts to find Eldorado: the first in 1594 and a second in 1617 (under King James I). Both attempts failed miserably and when Raleigh against orders raided a Spanish galleon on his second voyage, he was recalled by King James and executed.

Finely-engraved embellishments

A final note should be made regarding the two spectacular cartouches. Both are elaborately adorned with figurative motifs that have been drawn from Nicolas Janszoon Visscher’s 1658 map (although with important variations). The motifs stand out crisply in their magnificent original coloring. In the lower-left corner, we find the title cartouche surrounded by a composite scene of Native American life. The dominant figure is the chief to the left of the title box, who seems to be receiving offerings or inspecting crops. Further to the right, we find additional presenters leaving and approaching, as well as two children and an agitated man drawing his bow. The title box itself, while simple, expresses the great duality of the New World: atop the box, we find two open-mouthed serpents seemingly ready to strike at any moment, while at its base lies the rich golden bounty that drew so many to their untimely deaths in strange lands.

The second cartouche, in the upper right corner of the map, is a droplet-shaped plaque carried by four distinct figures. In the upper left corner is an angel. To her right is another pure woman holding a golden cross and seemingly staving off a demonic-clawed figure, which has lost his grip and is falling away. On the lower left, we find another generic Native American chief seemingly engaged in assisting the angel. Roughly translated from the original Latin, the text reads: America has its name from Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine who was sent out by the auspicious King Emanuel of Portugal, from Cadiz, in the year 1497. The first out of Europe, although Christopher Columbus, of Genoa, in the year 1492, on the order of Ferdinand, King of Castile, found the American islands Hispaniola, Cuba, and Jamaica.

Cartographer(s):

Frederick de Wit (1629–1706) was a Dutch cartographer and artist who drew, printed, and sold maps from his studio in Amsterdam. He was a pioneer of Dutch Golden Age cartography, and the founder of one of the most famous map-publishing houses in Amsterdam. He was born in Gouda but moved to Amsterdam at the end of the Thirty-Years-War (1618-48), which had engulfed most of Europe and ultimately liberated the Netherlands from centuries of Spanish dominion.

Soon after arriving in Amsterdam, probably in 1654, De Wit opened a printing shop named The Three Crabs (De Drie Crabben). A year or two before, he had married Maria van der Way, the daughter of a wealthy Catholic merchant, and this may have helped secure the funding to start his new operation. His aspirations as a cartographer were nevertheless made clear when he shortly after changed the name to The White Chart (Het Witte Pascaert), under which he gained international renown.

In the latter half of the century, De Wit began drawing, copying, and publishing atlases and maps. By the 1670s he was issuing large folios with up to a hundred maps in each tome, including a famous nautical atlas in 1675. From 1689, De Wit received a state privilege from the Dutch government to draw and issue maps. This protected his work from the illegal copying known from his earlier charts. De Wit was among the first to apply extensive coloring and his original color atlases and continental charts remain highly sought after to this day.

Following De Wit’s death in 1706, his wife ran the business for four years before selling it at auction in 1710. Their only surviving son was a successful merchant in his own right and had no interest in taking over. At the 1710 auction, most of De Wit’s plates were sold to Pieter Mortier, another Amsterdam cartographer and engraver. After passing the firm to his son, who teamed up with Johannes Covens, the firm became Covens & Mortier, the largest cartographic publisher of the eighteenth century.

Condition Description

Excellent old color. Numerous repairs to centerfold and margins. Trimmed short on bottom.

References