Duchetti’s extremely rare 16th-century broadsheet with 63 small busts of French kings from Faramund to Henry III.

Omnium Regum Galliae usquae ad praesentem iccones.

$2,800

1 in stock

Description

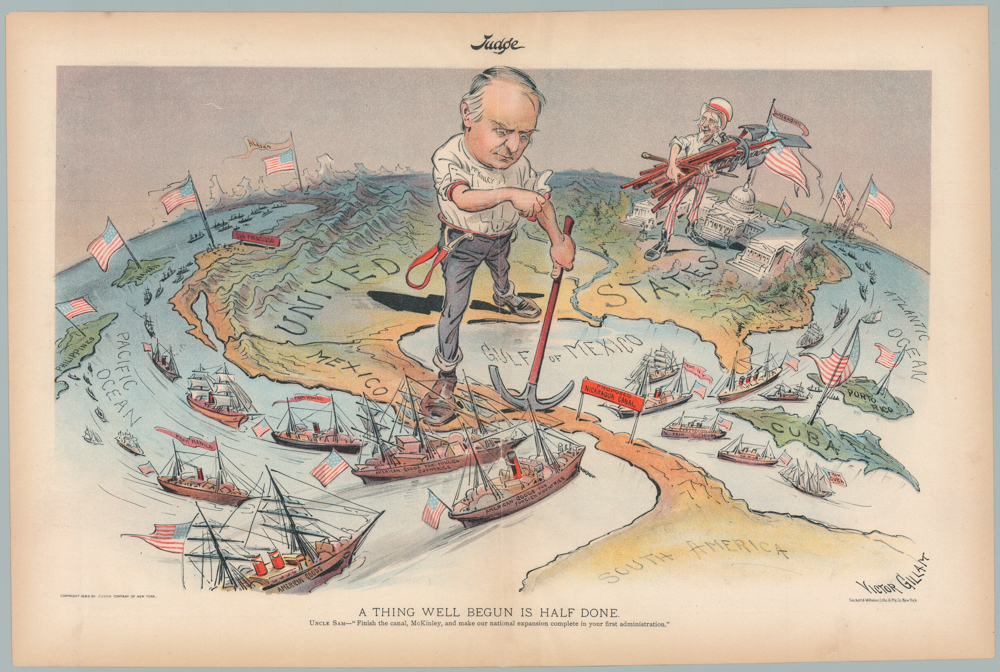

This rare 16th-century broadsheet was produced by Rome-based engraver and printmaker Claudio Duchetti and published in 1596. The sheet consists of a registered panorama with 63 portraits of French Kings, beginning with the quasi-myological King Faramund, who founded the Merovingian Dynasty in the 5th century. The portraits culminate in the ruling King Henry III (1551-1589), the last Valois king of France. At the end, an empty space has been left for the king’s heir, indicating some uncertainty that would follow Henry’s death. On this example of this rare sheet, a caricature of such an ensuant king was later drawn in pencil.

The maker is identified in the final pixel, which also dates the sheet:

Nomina et Effigies Christianissimor, Regum Galliae ex Historijs Medaglijs nec non alijs antiguitatibus diligenter et accurate extractis Romae. Apud Heredes Clauij Duchetti 1586

The date is significant because it marks the last year Duchetti was active. Moreover, it was created only two years before Henry III was assassinated, which threw France into renewed religious turmoil.

This print probably comes from Duchetti’s 1586 publication of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (The Mirror of Roman Magnificence). This work was created by Antonio Salamanca and Antonio Lafreri, Duchetti’s uncle. For more on the relationship between Duchetti and Lafreri, see the cartographer’s bio below.

Context is Everything

At the end of the 16th century, the French monarchy underwent profound political instability and religious conflict, culminating in the Wars of Religion (1562–1598). The French monarchy was traditionally a centralized authority under the Valois dynasty. Still, by the late 1500s, the crown’s rule had been severely weakened by decades of civil war between Catholics and Huguenots (French Protestants). The struggle between these two religious factions was exacerbated by rival noble families, such as the Catholic Guise family and the Huguenot-leaning Bourbons, who vied for control of the kingdom.

King Henry III, the last Valois king, struggled to maintain control, and his assassination in 1589 marked the end of the Valois dynasty. His death left the throne to Henry IV, the first Bourbon king, a Protestant. This created a crisis of legitimacy in a predominantly Catholic France. To consolidate his power and end the religious conflict, Henry IV famously converted to Catholicism in 1593, reportedly saying, “Paris is worth a Mass.” His Edict of Nantes in 1598 granted limited religious tolerance to Protestants, bringing an uneasy peace to the kingdom.

Mythology Surrounding French Kingship

The French monarchy was steeped in centuries of royal mythology that helped to legitimize the king’s authority. The French kings were seen as God’s appointed rulers, often referred to as rex Christianissimus (Most Christian King). They were believed to possess the divine right to rule, and various myths supported this belief. Central to this mythology was the notion of the king’s direct lineage from the early Merovingian and Carolingian rulers, mainly through the legendary figure of King Pharamund (or Faramund).

Pharamund, a semi-legendary king, was thought to be the founder of the Merovingian dynasty in the 5th century. Although historical evidence for his existence is dubious, he played an important symbolic role in French royal ideology. By tracing their lineage back to Pharamund, French kings connected themselves to a continuous line of divine authority stretching back to the origins of the kingdom itself. This myth reinforced the monarchy’s legitimacy, even during times of crisis, such as the religious wars of the late 16th century. Pharamund’s importance also lay in his association with sacred kingship, where French kings were political leaders and protectors of the Church and the faith. This belief was embodied in the sacred, the holy coronation ceremony of the French king, which took place in Reims and symbolically tied the monarch to the church, reinforcing the notion of divine right.

At the end of the 16th century, the Pharamund mythology was crucial in supporting Henry IV’s claim to the throne. Despite his Protestant background, his eventual conversion to Catholicism and his emphasis on the continuity of royal authority helped secure the loyalty of French Catholics. The ancient myths surrounding figures like Pharamund provided a powerful ideological tool for ensuring political stability in a deeply divided France.

Census

This sheet is scarce, with no individual listings of the print in the OCLC. An example in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (accession no. 41.72[3.99]) was published in Duchetti’s Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (1586). Still, whether the broadside was a standard part of this work is unclear.

Later, in the 17th century, Duchetti’s designs were emulated for the House of Habsburg and the Counts of Flanders.

Cartographer(s):

Claudio Duchetti was a prominent Italian engraver and print publisher based in Rome during the late 16th century. Active from around the 1570s to the 1580s, Duchetti came from a notable family of printmakers. He was the nephew of Antonio Lafreri, a highly influential figure in the Roman print trade. After Lafreri’s death in 1577, Duchetti continued the family business and became one of the key figures in the production and distribution of prints in Rome. His workshop was known for producing engravings of maps, classical antiquities, religious subjects, and popular imagery, catering to the growing demand for printed material during the Renaissance.

Duchetti’s prints often reflected his time’s intellectual and artistic currents, appealing to scholars and collectors interested in Italy’s classical heritage. His work contributed to the spread of visual culture across Europe and was part of the more significant movement of cartography and printmaking that characterized the late Renaissance. Although he did not achieve the same lasting fame as Lafreri, Duchetti’s role in maintaining and expanding the family print business established him as a significant figure in the history of Roman publishing.

Condition Description

Old margins on all sides, with some wear. Backed at the fold.

References

![Das Jahr der Kirche [The Year of the Church]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NL-01244_thumbnail-1-300x300.jpg)

![Das Jahr der Kirche [The Year of the Church]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NL-01244_thumbnail-scaled.jpg)

![Das Jahr der Kirche [The Year of the Church]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NL-01244_thumbnail-scaled-300x300.jpg)