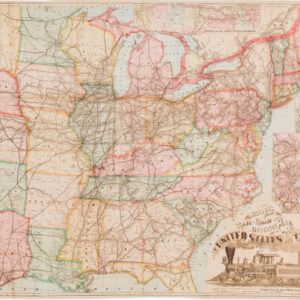

Colton’s spectacular wall map of a rapidly expanding America.

Colton’s Map of the United States of America, The British Provinces, Mexico and The West Indies Showing the Countries From the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean

Out of stock

Description

Colton’s 1854 large-format map of the United States is not just a visual masterpiece in cartography, it encapsulates the massive strides that the nation had achieved in only a few generations.

This monumental four-sheet wall map of the United States was produced at a time when the country was still taking shape and the violent throngs of Civil War had not yet engulfed the nation.

The map was produced in multiple editions, all of which were issued in the same important year (1854). Its most commonly found configuration of is as a joined wall map. Our example, however, has been sectioned and laid on linen, and done so in an uncommon manner, creating 24 large panels, instead of the more common 84 panels. Consequently, it effectively functions as both a folding map that can be easily stored and brought out as desired for study and conversation, or as a striking and decorative wall map to be framed and displayed on a wall.

Delineating and naming Kansas

More importantly perhaps is the fact that this is the rare third edition of the map, in which Kansas is named for the first time. Both Kansas and Nebraska formally became U.S. Territories on May 30th 1854, when President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act into law. This development was pushed through in part due to feverish ambitions of constructing a Transcontinental Railroad through this region, and presumably occurred at roughly the same time that the first edition of this map was issued. Consequently, Kansas remained undefined in the first state of this map.

Kansas was subsequently delineated but not named in the map’s second state, and would only be honored with a territorial label in the third state, as here. Exactly what prompted the Colton firm to tread so carefully in the second issue is unclear. Perhaps things were changing so rapidly that the outcome was still unclear. In any case, the amendment was clearly considered of sufficient importance to warrant a third edition with its formal label of KANSAS. Furthermore, Colton also published another hugely influential map in 1854, which focused explicitly and exclusively on the new Territories of Nebraska and Kansas. This map was then, as today, considered the most detailed and reliable depiction of these territories from the year they were created. Kansas would only achieve statehood in 1861.

Shifting territorial boundaries in the West

Being among the most important American mapmakers of his time, Colton naturally possessed abundant information and older maps and plates to draw upon when compiling the densely inhabited eastern part of America. But as with so many maps from this period, the story of this map is really found in the West. The inclusion of Kansas is just one of many interesting and age-specific features that characterize this map and make it one of the most poignant visualizations of the United States in the middle of the 19th century.

Although still part of a larger ‘Indian Territory’ that stretched into Kansas as well, the shape of what would one day become Oklahoma is clearly identifiable on Colton’s map. Its characteristic panhandle has nevertheless been distinctly colored and separately classified. During the early 1850s, this strip of land underwent a number of statutory and affiliative changes. Thus, in the first edition of this map, Colton included the panhandle as part of Texas, but from the second edition onward these public lands have been re-classified as ‘unorganized territories’. The subsuming of these lands first to the ‘Indian Territories’ of Oklahoma in 1890 and later to the new state of Oklahoma (established in 1907), was still very much in the making when this seminal map was published.

Oklahoma is just one obvious case in which the United States does not yet quite look like itself. In fact, a closer inspection reveals that there is still some way to go for many of the western states to resemble their present-day forms. Utah Territory remains one enormous entity with no trace of Nevada in sight. Nevada, of course, would be rushed into statehood in 1864 (30 years before Utah!), in order to ensure that it would support Lincoln in the General Election that same year. Nebraska is another clear example of the historicity of this map. It extends from the new border with Kansas in the south, to the Rocky Mountains in the west and the Canadian border in the north, effectively encompassing the modern states of North and South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, and of course Nebraska itself. As if to underline the persisting frontier character of this territory, Colton continues to use the somewhat antiquated label ‘Northwest Territory’ to designate this region.

Washington and Oregon Territories are also clearly delineated and extend all the way to the Rockies, encompassing what in 1890 would become the state of Idaho. In the southwest of the country we find similar scenarios, in which borders are gradually developing into the national entity we know today. We have already mentioned how Utah extends west all the way to California; immediately to the south we find the newly acquired Territory of New Mexico extending across an equally massive stretch from Texas in the east to California in the west.

Looking at the western part of America, one is struck by the massive ridge line of the Rocky Mountains, which cuts through the landscape. The mountains themselves have been rendered in exceptional detail for the time, and clearly show that Colton had had the opportunity to draw on the reports of John Charles Frémont, also known as ‘The Pathfinder’. Frémont was an American officer and explorer, and the first Republican presidential candidate. Between 1842 and 1846 he led several expeditions to explore the Rockies, producing extraordinary maps as a result. Aside from a decisive cartographic achievement, Frémont’s work epitomized the spirit of an age, in which intrepid explorers mapped wild lands under the aegis of the expanding American nation. The level of detail is echoed in other western ranges, such as the Sierra Nevadas, also explored by Frémont.

The 1854 Treaty of Mesilla (Gadsden Purchase)

When studying this fascinating map, anyone familiar with the southwest border will immediately notice a glaring incongruity with the present-day configuration. We have already mentioned the importance of the year 1854 in the formation of territorial boundaries within the United States. One of the most decisive steps in that regard has nevertheless been omitted from Colton’s chart. The Treaty of Mesilla, more popularly known as the Gadsden Purchase, saw a significant stretch of the U.S.-Mexican border redrawn following the acquisition of some thirty million acres of land from Mexico in 1854. However, the treaty was not signed until June of that year, and even in Colton’s third edition of this map, he refrains from incorporating this sensitive political issue and depicts the border with Mexico as it had been since the Mexican-American War (1846-48); it was not until the 1856 issue of this maps that the Gadsden Purchase was recognized and included.

The Gadsden Purchase sprang from border disputes following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which brought a formal end to the Mexican-American War on February 2nd, 1848. While the treaty was quite specific in terms of where the border was to be drawn, the job of securing that border from Indian attacks fell to the Americans. The Mexican government soon claimed that the U.S. was failing in this regard and demanded large sums in compensation for their losses. In 1853, the newly appointed U.S. president, Franklin Pierce, appointed James Gadsden as the ambassador to Mexico. The appointment came with a specific brief: purchase as much land in northern Mexico as possible. Initially, the idea was to acquire large swathes including all of Baja California, Chihuahua, Sonora and beyond. The Mexican government was not interested in selling further territories to the United States, but at the same time wanted to avoid war at all costs. Moreover, Mexican president Santa Anna desperately needed funds for his government and so a deal was brokered.

Once the Americans realized that they were not going to get all the desired territories in a negotiated purchase, efforts were concentrated on the wide strip of land immediately south of the Gila River. American surveyors had identified the broad Mesilla Valley as the ideal corridor for their new railroad. In December 1853, an agreement was reached in which the United States bought 30,000 square miles from Mexico for 10 million dollars (roughly equivalent to 3.5 billion today). The southern border of the United States was forever re-drawn, and our map is one of the last monumental Colton maps to depict the older state of affairs.

A skillfully-executed decorative scheme

A final note should be made on the decorative elements of this map. In addition to a visually powerful color scheme that subdivides the entire country into states and territories, the map is covered with an array of small symbolic or evocative vignettes. These include vivid renditions of American wildlife: deer in Kansas; a bear in the Northwest Territory; beavers north of the Great Lakes; a moose, wolves, and arctic foxes at play in Canada; and exotic birds in the Caribbean. Other well-known motifs include traditional images of frontier life: trapping, hunting, canoeing; scenes of Native Americans engaged in ritual dance; and a wagon trail scene in central Oregon. The maritime space is also full of enticing and extremely well executed images. Many of these are different kinds of ships, but they also include identifiable phenomena such as volcanos and specific coastal views, as well as characteristic Central American crops such as sugar cane and palm trees.

At the bottom of the map we find two insets. In the lower left corner, the publisher has included a rather detailed little map of the Central American isthmus, endowed with its own nation-based color-scheme, border graticules, a title, and two pictorial vignettes, one of which depicts an early archaeological discovery. The region has of course been featured because of its importance on the route to California, in which passengers sailed down from the Atlantic, made the overland trek across the isthmus, and then continued on again by sea up the west coast.

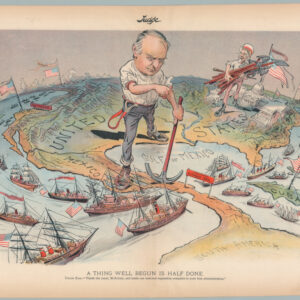

In the lower right side of the map, squeezed in between the general map’s table of Statistics of the United States and Table of Distances, we find a similar inset of the West Indies archipelago. This too is quite detailed and has its own title, scale bare, graticules, and landscape vignette. While seemingly reasonable additions to this type of map, both insets are in fact reflections of the rising geo-political interests entertained by America at the time. Such outward aspirations would of course soon be thwarted by internal strife (i.e. the upcoming Civil War), but by the end of the century, the United States would make her heavy presence felt in both of the inserted regions.

Cartographer(s):

The Colton Mapmaking Company was a prominent family firm of cartographic printers, who in the nineteenth century were leaders in the American map trade. Its founder, Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800-1893), was a Massachusetts native who in 1830 moved to New York City and slowly began setting up his publishing business, which in the beginning drew heavily on licensing maps by established engravers such as David H. Burr, Samuel Stiles & Company, and later Stiles, Sherman & Smith. Smith was a charter member of the American Geographical and Statistical Society, as was John Disturnell. This connection would later benefit Colton, in that it helped him to acquire the rights to several important maps.

By the 1840s, the Colton firm were producing their own maps. They produced anything the markets desired, from massive and impressive wall-maps to pockets guides, folding maps, immigrant guides, and atlases. One of the things that set the Colton company aside from many of its contemporaries in terms of quality, was the insistence that only steel plate engravings be used for Colton maps. These created much more well-defined print lines, allowing even minute features and labels to stand out clearly. By 1850, the Colton firm was one of the primary publishers of guidebooks, immigration itineraries, and railroad maps in America.

In the 1850s, Colton’s two sons, George Woolworth and Charles B., were brought on board to the firm. This inaugurated a process of expansion in which the company began taking international commissions and producing wholly independent maps and charts. From 1850 to the early 1890s, they also published several school atlases and pocket maps. The firm continued until the late 1890s, when it merged with a competitor and then ceased to trade under the name Colton.

Condition Description

Segmented and laid on linen, as issued. Several splits in the linen. When folded, measures 13½ x 10¼ inches.

References

Cohen, Paul E. 2002 Mapping the West. America’s Westward Movement 1524-1890. Rizzoli: New York

Wheat Transmississippi 776, p 161, for first issue 1853; Wheat Gold Region 255; Martin & Martin, Maps of Texas and the Southwest, #43.