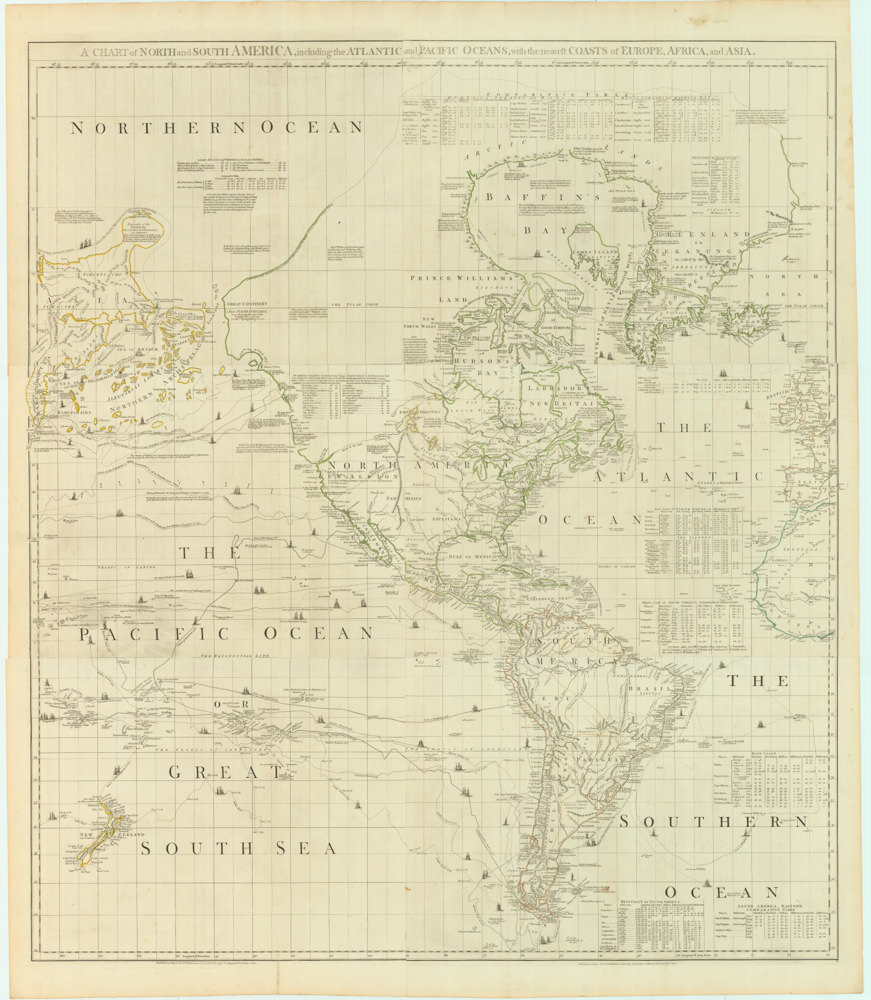

Sayer and Bennet’s monumental chart of North America in revolt.

A New and Correct Map of North America, with the West India Islands. Divided According to the Last Treaty of Peace…1779.

Out of stock

Description

British mapmakers Robert Sayer and John Bennet issued this stunning four-sheet map of continental North America during the bloody middle point of the Revolutionary War. It reflects the dramatic changes and shifting frontiers of late-1700s America, and it stands out for the quality of its cartographic craftsmanship.

Some of the finest English mapmakers of the era produced this map, and it was published in highly esteemed volumes printed in London. Compiling this map constituted a delicate tightrope walk between the royal cartographers’ loyalty to the Crown and their fidelity to realities on the ground.

Having been produced following the end of the French and Indian War (a.k.a. The Seven Years War, 1756-63) and during an age marked not only by revolution but also by a constant pushing of frontiers through exploration, the mapmakers load the chart with indigenous information and place names – especially in the west. Forts and wagon trials are shown in the Mississippi Valley and all along the western foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. This frontier theme is further echoed in the title cartouche, elaborated with romanticized Indian figures and American fauna like a slain mountain lion, Carolina parrots, an alligator, and the pelt-yielding beaver.

Editions and publication history

Sayer and Bennett drafted the map on an original by Bowen & Gibson, issued in 1755 before the Seven Year War between England and France (1756-63) and the subsequent colonial revolution that eventually created the United States. The map quickly became iconic due to its monumentality and the large amounts of continuously updated information made available with each new edition. Each major stride in the political development of North America was manifested in new and updated editions of the map. Thus, the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763 saw a new edition, whereas the American Revolution prompted the creation of several new editions, both during and after the war for independence.

From 1775 – the year that the American Revolutionary War became a military confrontation, the map began to be included in some of the most influential English atlases of America produced in the era (including works by Thomas Jeffreys, William Faden, and indeed Sayer & Bennet). Once the struggle for independence had begun and the military conflict between Britain and her American colonies escalated to full-fledged war, the scope and detail of the map were gradually expanded using information compiled by various colonial administrations and other loyalists.

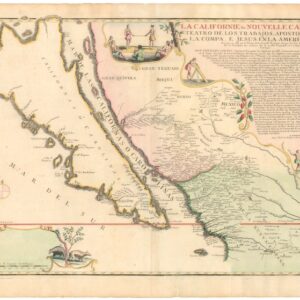

Primary among these was Governor George Pownall’s Topographical Description of North America, which drew mainly on Lewis Evans’ map of the Middle British Colonies of North America from 1755 (Mulkearn 1949). These sources dramatically improved the American geography on the map – including new insets of Hudson Bay and the mouth of the Colorado River as explored by Father Eusebio Kino. The latter was especially significant, as it definitively dispelled the notion that California was an island.

In sum, this is a dramatic and stunning chart in which some of the best mapmakers of the era have captured North America in the midst of revolution and the prolonged expansion into the unknown that created the United States we know today. It is a political map, an historical map, and above all, a masterful example of how vital maps were in the mental creation of an empire.

Cartographer(s):

John Bennett was one part of the famous 18th-century writing partnership, Sayer & Bennett. Bennett was originally a servant to Robert Sayer, who was a prominent printer and map seller in London. Sayer took Bennett in as an apprentice in 1765 and nine years later, in 1774, he officially became Sayer’s partner in the business. Together they produced numerous highly sought-after cartographic publications, just as they made a fortune on printing advertisements and other commercial material.

The partnership initially went very well, with Bennett taking over an ever greater part of the business from Sayer. By 1777, Bennett owned more than 30% of the firm, but within a few years, he began showing signs of mental health problems. Sayer hoped that a nine-month stint at a London asylum in 1783 would help, but it was to no avail and the following year Robert Sayer was forced to dissolve their otherwise successful business.

Bennett died shortly after, in 1787.

Robert SayerRobert Sayer (1725–1794) was a leading publisher and seller of prints, maps, and maritime charts in Georgian Britain. He was based near Fleet Street in London. This was a business he had taken over from his brother in 1748 after he had won it by marrying the widowed daughter-in-law of another famous London map seller, John Overton.

After taking on his servant John Bennett as an apprentice in 1765, and later partnering up with him, the firm of Sayer and Bennett became one of the most important map houses of late 18th century Britain. From then on, the Sayer & Bennett firm was particularly well-known for their maps and atlases focusing on the Americas during a time of great upheaval and change (i.e. the French and Indian War, and especially the American Revolution).

In the beginning, many of these publications would have an obvious British slant, but as things progressed, Sayer increasingly realized the potential in creating reliable maps of an independent North America. Consequently, Sayer & Bennett produced some of the most significant charts and atlases of the British colonial possessions in America and later of the early United States.

Condition Description

Excellent condition overall. One area of soiling on the first sheet at bottom (only visible in verso). A few minor spots of foxing and other imperfections in the margins. Old/original outline color.

References

Mulkearn, Lois (1949). The Biography of a Forgotten Book—Pownall's "Topographical Description of...North America”. The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 43,1: 63-74