The definitive reconnaissance of Greenland’s east coast and a milestone in Arctic exploration.

Undersögelses-reise til östkysten af Groenland: efter Kongelig Befaling, udført i Aaren 1828-31.

$2,000

1 in stock

Description

Danish naval officer Wilhelm August Graah (1793–1863) occupies a particular place in the history of Arctic exploration. During the 1820s, in an era when much of Greenland’s coast remained poorly charted, Graah led two crucial survey expeditions to map the inhospitable coastline of the enormous Arctic island.

His role as a surveyor and cartographer in the first expedition (1823-24) was part of his regular duties as a naval officer. The aim was to survey a number of inlets, harbors, and other locations in West Greenland, which at the time was the island’s economic hub (primarily international whaling). The overarching goal of the survey was to build an empirically anchored pilot chart (Situations-Kaart), and Graah’s published report (1825) was an essential step in that direction. The skill, determination, and clarity with which Graah fulfilled this assignment made him an ideal candidate to lead a far more trying and critical mapping mission a few years later.

The second expedition (1828-31), which Graah was appointed to lead, was a royally mandated reconnaissance mission that sought to delineate the isolated and uncharted southeastern coast of Greenland. During this voyage, Graah combined traditional naval surveying techniques with reconnaissance in local craft and in close cooperation with Inuit boatmen. This was highly unusual at the time, but the active involvement of indigenous peoples in exploration efforts not only improved the outcome but also dramatically increased the survival rate of Graah’s men. Over the following decades, relying on local Inuit for knowledge and assistance would become one of the key principles in successful Arctic exploration, underscoring the paradigmatic importance of Graah’s work.

Charting of Greenland’s East Coast

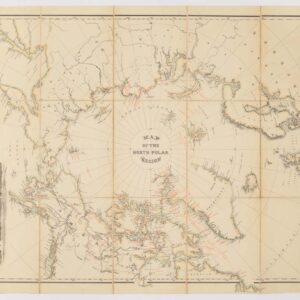

The meticulousness of Graah’s 1825 report made him the ideal choice for a new mapping mission on Greenland’s east coast. The east coast had been partially mapped a few years prior to Graah’s expedition. William Scoresby Jr., a whaling captain with strong scientific interests, made systematic observations and a charting run in the summer of 1822. His survey laid down the coastline roughly between 69° and 75°N and corrected serious longitude errors on earlier maps. He named over 80 locations, building an east coast toponymy that has endured. The following year (1823), the British pendulum-experiment voyage under Douglas Clavering (with Edward Sabine aboard Griper) pushed north into the same sector, reaching about 74°N and establishing an observatory on Sabine Island. Clavering formally surveyed the coast between roughly 72°30′ and 74°N, joining and extending Scoresby’s pioneering work. Graah’s brief was to complete the work started by Scoreby and Clavering.

The expedition left in 1828 and would take three years to complete. Graah’s mandate was explicit and twofold: by royal order, he was to explore the little-known east coast in search of any traces of the “lost” Norse settlements, and to produce accurate observations for modern charting. The aim was to cover Greenland’s east coast from its southern tip to roughly 70°N, thus completing the work begun by Scoresby and Clavering.

Graah sailed from Denmark in a navy brig, but once they reached Greenland, the expedition relied far more on local umiaq: large, open kayak-like boats constructed by stretching hides across a framework of driftwood or whale bones, used mainly for the transport of families and goods or for whale-hunts. Due to the extremely variegated coastline and the presence of both pack- and sea ice, Graah’s mission was highly dependent on the skills and knowledge of indigenous pilots. This hybrid approach was unusual at the time, but constituted a pragmatic approach to an otherwise deadly littoral.

Although Graah was unable to follow the coast to the high latitudes that his royal brief demanded, his teams penetrated and charted long stretches of Greenland’s fjord-riddled southeastern coastline, between Cape Farewell and what today is Tasiilaq (formerly Angmagssalik). In this remote region, which still bears the name given by Graah (i.e. King Frederick VI Coast), the expedition made accurate observations of fjords and coastal features and produced the first charts and topographical profiles. In doing so, Graah not only compiled the first empirically grounded description of this remote region, but also laid the foundation for later, more detailed surveys (notably those by Gustav Holm and others in the 1880s). Graah’s impact is reflected by a number of toponyms commemorating his accomplishments (Graah Fjord, Graah Peninsula, and the Graah Nunataks).

In addition to the decisive cartography, Graah’s legacy is his careful observational writing. He recorded interactions with the southeast-Greenland Inuit, noting key elements of their distinct culture. He wrote detailed descriptions of material culture, clothing, small-boat construction, and subsistence practices that later expeditions, ethnologists, and historians have used as primary evidence. His famous published account included geological and botanical notes contributed by the expedition’s naturalists and presented sketches and drawings that enriched nineteenth-century European understanding of Arctic environments. Graah’s narrative also describes cultural encounters in this frozen frontier.

The nature of Graah’s legacy

Seen together, Graah’s writings and charts amount to a single, overarching achievement: the conversion of vast, poorly understood Arctic coastlines into a functional cartographic resource. His work fused disciplined surveying practice with sustained on-site observation so that narrative, place-name, and chart come to reinforce one another. The result was not only better maps but a repeatable approach to Arctic coastal description that made Greenland’s shores legible to both seamen and scholars. They are, in essence, a synthesis of naval competence and exploratory curiosity. That synthesis is the source of Graah’s lasting legacy. His publications provided the conceptual and practical scaffolding upon which later explorers and scholars built. Moreover, he humanized the indigenous inhabitants by making them a key part of his explorations.

Historically, Graah’s work marks a pivotal moment in the history of Arctic mapping: the slow shift from fragmentary, impressionistic reports to the disciplined, reproducible cartography that not only made further exploration possible, but also safer and more systematic.

Cartographer(s):

Wilhelm August Graah (1793-1863) was a Danish naval officer and Arctic explorer. He is best known for his expedition to East Greenland, during which he teamed up with local pilots and used local craft to explore the rugged, isolated coastline. In 1828–31, Graah led a royally mandated expedition to southeastern Greenland to find traces of the putative Eastern Norse settlements and map the isolated eastern littoral. Once there, he relied on local umiak boats and Inuit pilots for near-shore work. With his team, he charted and named large stretches of what he called the King Frederick VI Coast: some 550 km of previously poorly documented shoreline. Graah published a detailed account of the voyage (Danish edition, 1832; English translation, 1837), combining practical hydrographic observations with natural-historical and ethnographic notes that proved helpful to later navigators, naturalists, and mapmakers. His narrative and charts both tightened the geographic knowledge of Greenland’s southern coasts and left a strong toponymic and cartographic legacy.

Condition Description

Good.

References